So there you are, a day or two after knocking out some chin-ups and pull-ups in the gym, when all of a sudden, you realize that your abdominal muscles (abs, for short) are just as sore as your mid-upper back – or perhaps even sorer. What gives? Are pull-ups and chin-ups supposed to make your abs sore, or is there something wrong with you? Don’t sweat it; in this article, I’ll cover what this all means, along with other helpful information to help you understand and eliminate this issue altogether.

And no, there’s nothing wrong with you.

Abdominal muscles often become sore from pull-ups and chin-ups due to the intense isometric demands they endure throughout the exercise. This is most notable with the rectus abdominis muscle. You’ll likely experience reduced soreness or even no soreness at all as your muscles adapt to these demands.

All of this is surprisingly a bit more common than most people realize. So let’s look at what’s happening and how to avoid or eliminate the issue entirely. After all, why be just a physically strong individual when you can be a physically strong AND knowledgeable individual?

Related article: Horizontal vs Vertical Rows: Differences & Benefits of Each

Which core muscles are getting sore?

The “core” and “abdominals” are often used interchangeably, but there are a couple of things going on here that you should be aware of.

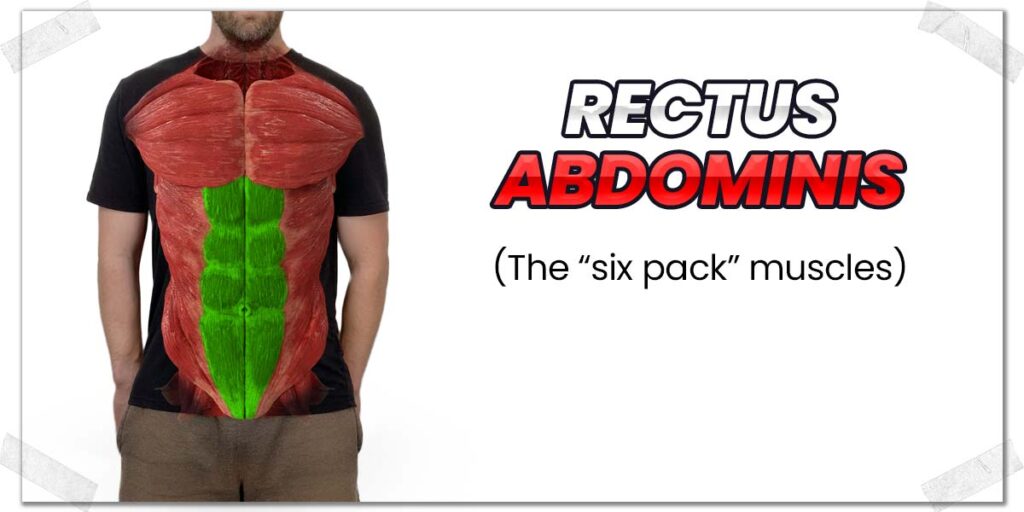

The abdominals are one of the muscles that comprise the “core” muscles. The core is not exclusively the abdominals themselves. When people say “abdominals” or “abs,” they tend to refer to the super popular and well-known muscle anatomically known as the rectus abdominis.

But just so we’re clear: in a basic sense, the “core” muscles refer to the muscles that wrap around the torso of the body. Their role is to provide stability, produce movement of the torso, and allow for the effective transfer of force within the extremities.

Some of the notable core muscles include:

- The transversus abdominis

- The internal obliques

- The external obliques

- The multifidi

- The erector spinae

- The rectus abdominis

Again, I’m using the term “core” rather loosely in terms of the specific muscles it comprises. The goal of this article isn’t to get lost in the weeds of technical anatomy; the goal is to merely raise your general awareness of some of the critical muscles around the midsection of your body.

But of all these particular muscles mentioned, the rectus abdominis deserves the closest inspection when discussing the phenomenon of experiencing abdominal soreness after banging out some pull-ups or chin-ups.

Keep reading to learn why this particular muscle is likely the one causing the majority of your soreness (and what can be done to remedy the issue)!

What’s happening to core muscle function during pull-ups?

Ever notice how the lat pulldown exercise or underhand-grip pulldown doesn’t produce any soreness in your abs whatsoever, yet pull-ups and chin-ups (which are the exact same movement) do? That’s because when you’re performing lat pulldowns, your torso essentially gets to sit back and relax while your arms and mid-upper back do all the work.

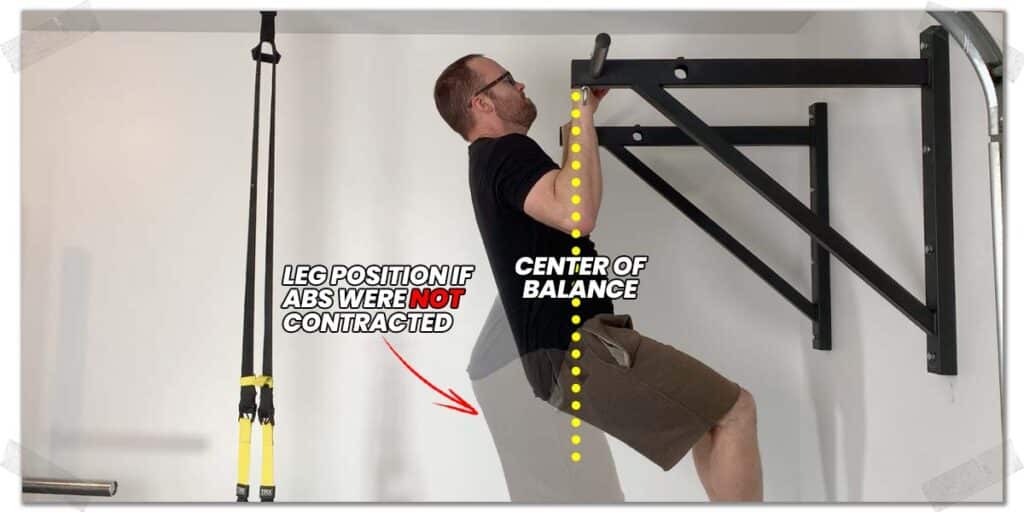

When hanging on a pull-up bar, your lower body can freely swing forwards, backwards, side-to-side, and even twist or rotate – it’s essentially free to move in any direction. But effective pull-ups require the lower body to fine-tune its position when performing the exercise – and the position of the lower body is primarily determined by the core’s ability to contract and produce an overall bracing effect.

This bracing effect is necessary for two particular reasons:

- To resist unwanted movement (to achieve better control of the exercise)

- To help position – and hold – your body in a way that permits your head to clear the bar when pulling yourself up.

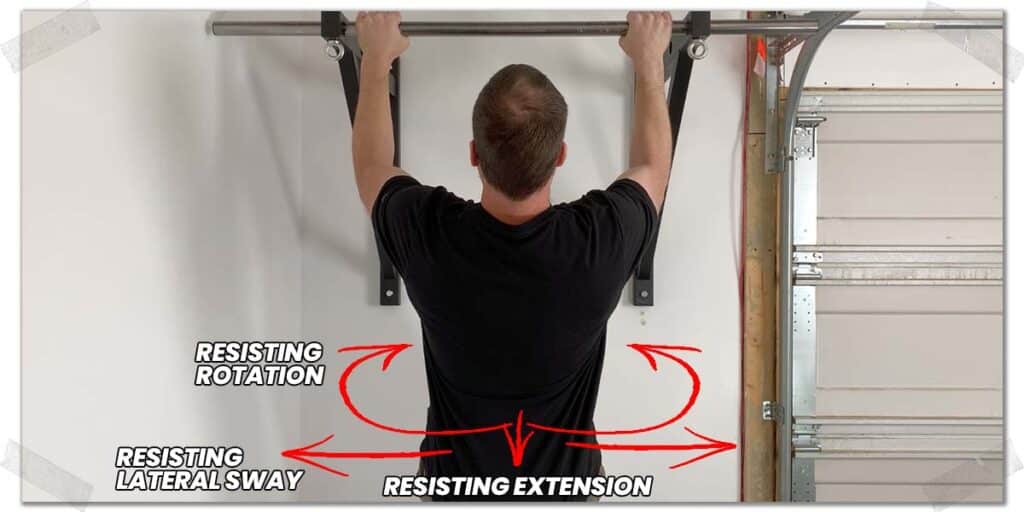

Resisting unwanted movement when hanging (twisting, bending, etc.) is a group effort from all of your core muscles (through a phenomenon known as co-contraction). So, any core muscle helping to resist movement when you hang has the potential to become sore due to being challenged. But it’s the second mentioned point that’s probably playing a more extensive role in your abdominal soreness.

Regarding the second point: to clear your head from the bar, the upper body will lean back at an ever so slight angle. When this happens, we reflexively (automatically) contract the rectus abdominis to help maintain the center of our body’s balance point and to prevent our lower back from excessively arching (which can be uncomfortable or painful if not performed).

The sole function of the rectus abdominis muscles (i.e., the “six pack” muscles) is to shorten the distance between the bottom of the rib cage and the hip bones (by producing the traditional “crunching” motion). When you hang from a bar, your rectus abdominis muscles are holding a constant contraction (crunch) to ensure your hips (and thus, your legs) don’t rotate too far backwards.

Now, your abs will need to produce – and sustain – a fair amount of force to hold this mild-to-moderately crunched position against the freely-hanging lower half of your body throughout the exercise. After all, they’re fighting against the weight of the lower half of your body, which is no small task.

Pro tip: Your hip flexor muscles are actually undergoing quite a bit of effort as well to help keep your legs in front of you to create an ideal balance point beneath the bar. For the sake of this article, however, the focus is predominately on the rectus abdominis.

It’s not conceptually different from holding the traditional hollow (banana) position when lying on the floor. You can try it for yourself:

- Lay on the floor with your arms directly above your head.

- Lift (and hold) your shoulder blades off the floor.

- Curl your hips backwards so that you crunch your lower abs.

- Lift your legs off the floor while keeping your knees straight.

Your body should now resemble the shape of a banana, and you should feel your abs and the rest of your midsection working hard to hold this position.

This is what happens during the pull-up or chin-up, with the exception that this position is being held in the vertical position (hanging on the bar) rather than the horizontal position (laying on the floor).

Anatomy fact: Depending on how you move and control your torso throughout the exercise, the internal and external oblique muscles and transversus abdominis muscle can also play an extensive role in achieving torso stability, but they are not discussed within this article

Understanding isometric muscle contraction

When a muscle contracts and produces movement (such as when your elbows bend to lift yourself upwards during the pull-up), it’s known as a concentric muscle contraction. This is the most common type of muscle contraction people are familiar with and the one they think of when they think of muscles contracting.

However, muscles can also contract (tighten up) without producing physical movement of our body. This is known as an isometric muscle contraction. Think of standing up tall and then bracing your stomach in anticipation of it receiving a punch. This bracing is an isometric contraction of your various core muscles.

Fun fact: There is another type of muscle contraction called an eccentric contraction, which refers to a muscle lengthening back to its resting state (after it has undergone a concentric contraction) in a controlled manner.

While your torso might not produce much (or any) movement during the pull-up or chin up, you can bet your bottom dollar it’s resisting movement at all times of the exercise, meaning it doesn’t get a break from contracting until your feet are back on the ground.

How to stop your abs from becoming sore during pull-ups

If you’ve got another pull-up or chin-up session coming up, but your abs are still toasted, or you just don’t want to experience sore abs again, there are some super simple steps you can take to ensure that only your back gets a workout and not your core.

What follows are some straightforward strategies you can consider implementing if you’re keen on still training your muscles in the exact same way without blasting your core or if you want to improve your core strength.

Strategy 1: Do lat pulldowns instead

If you want to keep hammering your back muscles and biceps with the exact same movement pattern as pull-ups and chin-ups, the easiest step to take is to switch over to performing lat pulldowns and underhand-grip pulldowns instead.

Pulling weight downwards (i.e., performing pulldowns) will target the same back and arm muscles as pulling weight upwards (i.e., performing pull-ups and chin-ups). The only difference is the core musculature gets to take a largely passive role during pulldowns since you are seated with your lower body locked in underneath the thigh pads.

The only potential downside with this approach is if you’re training at home with a pull-up bar since you probably won’t have access to a lat pulldown machine. But this obviously isn’t a problem if you’re currently training at a local gym (since the lat pulldown machine is a staple in every facility).

Strategy 2: Stick with it and just “gut it out”

Another option to overcome the issue of sore abs from pull-ups is to keep performing the exercise and simply gut it out (yes, that pun was intended) until your abs accommodate the required amount of strength and endurance to no longer become sore.

I would only recommend this, however, if your abs aren’t deathly sore after your pull-ups; mild-moderate soreness isn’t an issue at all, and you can think of this as getting a two-for-one deal out of your pull-ups (an appropriate back exercise and core exercise as well).

However, if you find that your abs are immensely sore after pull-ups, it may be worth either reducing the frequency of your pull-ups (or the training volume itself, which refers to the number of sets and reps that you perform) for the time being.

If this is the case, I’d recommend holding off on pull-ups for the time being and instead focusing on strategy 1 and strategy 3. Once you’ve had enough time to effectively incorporate those approaches, you will likely have improved your core strength enough to try pull-ups again.

Strategy 3: work on core strength (try these exercises)

A weak core can be a recipe for disaster. Not only does it lead to decreased athletic performance, but it also leads to a higher incidence of lower back pain and injury.1,2

So the solution isn’t to stick your head in the sand and pretend like the issue doesn’t exist; the solution is to attack it head-on and eliminate the issue entirely.

While there are a billion core and abdominal exercises one could do to improve their midsection strength, here are some general concepts to be aware of when selecting which exercises might be the most effective (and safest). I’ll link a YouTube video of mine demonstrating some highly effective exercises to try right after the following points:

- Pick core exercises that not only challenge you to produce movement but also ones that challenge you to resist movement. The ability of the core muscle to resist unwanted movement is generally referred to as anti-rotation.

- Avoid traditional sit-ups. The traditional sit-up might do more harm than good. While there’s a lot to unpack here (too much for this article), the repeated lumbar spinal flexion from sit-ups can lead to lower back pain and disc issues.3,4 This is especially true if you have a history of lower back issues. Plus, it’s not the most functional exercise.

- The ab wheel can be a brilliant piece of equipment to develop core strength; just make sure it doesn’t bother your lower back. You can check out my article on ab wheel alternative exercises if it does.

- Avoid the Russian twist like the plague. It often leads to all sorts of problems for individuals. If you want to know why (and learn alternatives), check out my article on why you should avoid the Russian twist.

Developing the requisite core and abdominal strength required to eliminate soreness to these muscles might take a handful of weeks. Still, in otherwise healthy individuals, initial results should be noticeable within a month or so.

Don’t worry about blasting your core away for an hour every day; you likely only need to perform a few ab or core exercises a couple of times per week. You can certainly increase the weekly frequency of these exercises if you’d really like, but it probably isn’t necessary, especially if your midsection is a bit weak to begin with (it might need a day or two off to recover after each session).

Final thoughts

There’s really nothing wrong with (or even surprising about) experiencing sore abdominal muscles after pull-ups; these muscles actually undergo an extensive amount of effort during the exercise. It’s especially common in those who are new to the exercise or who lack higher levels of abdominal strength and endurance.

Pick one or more of the strategies listed within this article that you can implement and work it consistently. You should notice improvements to your core strength and decreases in abdominal soreness post-pull-up session within a few weeks.

References:

4. Axler CT, McGill SM. Low back loads over a variety of abdominal exercises: searching for the safest abdominal challenge. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6):804-811.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!