Whether it’s the snatch or the clean and jerk, a healthy set of shoulders is an essential component for performing either lift. Whether you want to perform these lifts for a lifetime or just want to bang out a few occasional heavy reps, you’re going to need shoulder mechanics that are on point.

And that’s not happening if you have pain in your shoulder when weightlifting. So, let’s get to the bottom of this issue and come up with strategies that will make a difference for you.

Shoulder pain from Olympic lifting can arise for many reasons. Due to the nature of the lifts, they require optimal shoulder mobility, shoulder stability, muscular strength and motor control. The absence of any of these factors will ultimately lead to dysfunction, pain, and poor performance.

So, with that being said, let’s unpack all of this in a straightforward manner so you can get your shoulder back to where you want it to be – strong, healthy, pain-free, and able to tolerate the clean and jerk and the snatch.

As we dive into the article, let’s start with a brief run-through of the functional demands the shoulder must meet if the Olympic lifts are to be performed successfully and without shoulder pain.

This brief understanding can be immensely helpful for a more intuitive understanding of shoulder dysfunction and how it can be resolved.

Functional shoulder demands of Olympic weightlifting

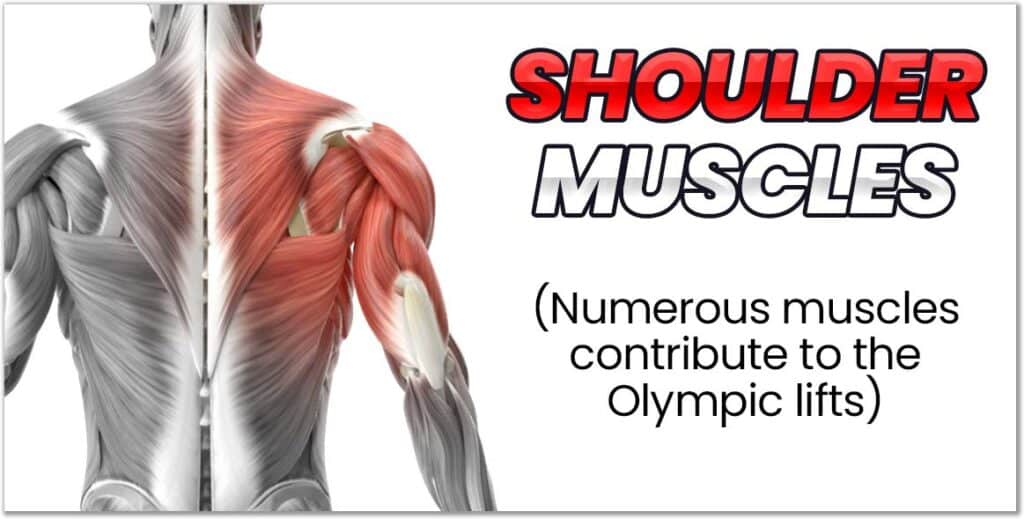

From the speed of each movement to the ranges of motion and resistance used, there aren’t many other sporting activities that demand the combined speed, range of motion, strength, and stability from the shoulder joint and subsequent muscles than Olympic lifting.

Essentially, the Olympic lifts demand everything from the shoulder.

With such demands imposed on the shoulder’s structures, it doesn’t take much to go wrong before dysfunction and pain arise during either the snatch or the clean & jerk (or both).

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, so whether you lack even a rather small range of motion, or a bit of joint stability, once one link “breaks,” the rest of your shoulder can be negatively impacted by the Olympic lifts.

Think of it like a loose thread on a piece of clothing; it can begin to unravel, becoming more prominent and affecting the fabric’s integrity.

So, the moment one of the “threads” becomes loose in your shoulder’s overall functional status, it’s imperative you don’t let it unravel any further. Get to the root cause and get it addressed before the integrity and function of your shoulder continues to unravel.

Pain generators of the shoulder

The shoulder is a pretty remarkable joint. It’s capable of all sorts of movements due to its design and the numerous muscles that work to pull it in pretty much any direction. But it’s also susceptible to incurring all sorts of dysfunctions, mechanical issues, and pain.

For the sake of this article, we’ll keep it simple and consider the primary pain generators of the shoulder to be the muscles, tendons, joints, and the joint capsule. Of course, there can be more pain generators than these (subacromial bursa issues, nerve issues, etc.), but they will be outside the scope of this article.

Some shoulder issues that I’ll be briefly mentioning but not going into detail (but are worth knowing) include:

Check out the links to those conditions if you want to learn more about them (they take you to a very reputable and trusted site on physical injuries and conditions).

Pain generator 1: muscles and tendons

When dealing with pain, lifters are most often interested in muscles and tendons since these are the structures they’re most often familiar with. And for a good cause, too; these structures tend to affect lifters and other athletic or otherwise physically active populations.

So, we might as well start here.

Muscles and tendons are prone to becoming sore and painful for numerous reasons. Sometimes this soreness and subsequent stiffness are appropriate, such as with delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which is the normal response muscles produce after a challenging resistance training or exercise session.

However, muscles can become overworked to the point where the soreness is painful due to different processes taking place. This type of soreness is typically the result of chronic (i.e., repeated) bouts of stress and strain on the muscle or tendon, which occur at a greater frequency or extent from which they can recover.

With tendons, this often results in the condition of tendonitis (which subsequently goes on to become tendinosis).

With muscles, the condition is known as a muscle strain, whereby the muscle has been over-exerted beyond its capacity, leading to pain and soreness within the muscle itself.

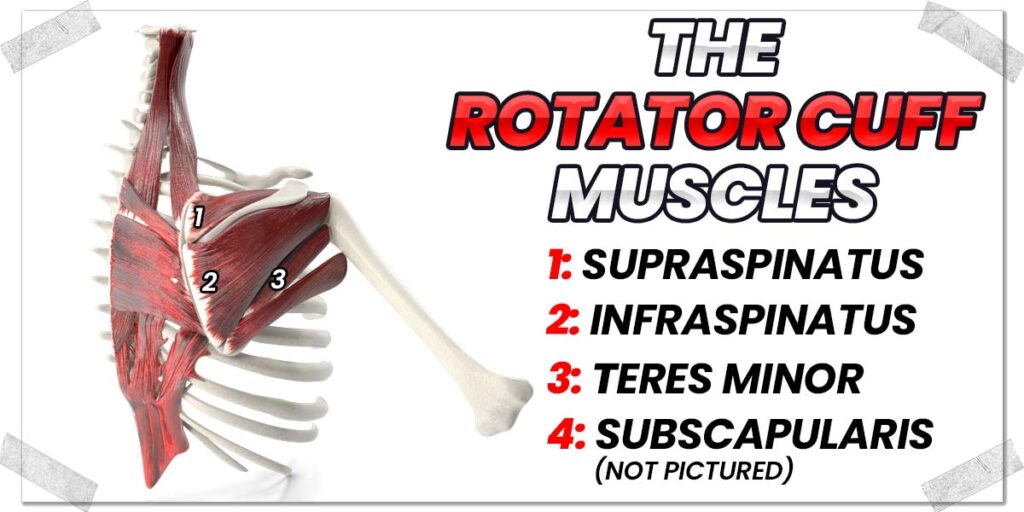

The rotator cuff muscles (and their subsequent tendons) are the most commonly affected shoulder muscles for shoulder strains, tendonitis, and tendinosis.

The rotator cuff refers to a group of four muscles. These are:

- The supraspinatus

- The infraspinatus

- The teres minor

- The subscapularis

Other nearby muscles can experience these issues (such as the long head of the biceps muscle and tendon, among a few others), but for the sake of this article, I’m keeping it limited to the most common issues.

What to do about this issue

Rehabbing irritated muscles and tendons is most often a very straightforward process. Unfortunately, it tends to be a slow one as well.

Don’t get discouraged, though. Learning how to load your muscles and tendons back to full health will come in handy for any similar future issues you face (a pulled hamstring, Achilles tendinitis, etc.).

To learn the full step-by-step sequence, check out my article, where I show you how to overcome stubborn tendon issues, backed up by the latest research by world-leading experts.

Pain generator 2: the shoulder joint

Anatomically, the shoulder joint is known as the glenohumeral joint. However, for the sake of this article, I’ll just call it the shoulder joint.

Often, joint pain is distinctly different from muscle or tendon pain. Pain arising from the ball and socket joint (as opposed to the muscles and tendons that cross over the joint) is frequently felt as a sudden, sharp pain that arises when the joint is moved into a position that it doesn’t like.

Also, it tends to be felt deeper within the shoulder rather than closer to the surface. However, keep in mind that this in no way guarantees that your pain is indeed arising from the joint.

There can be different reasons for joint pain to occur in the shoulder; however, in the absence of major shoulder trauma, osteoarthritis is the common culprit. This condition refers to the degeneration (breaking down) of the cartilage covering the ball and socket joint.

Pro tip: Though I will repeatedly mention the barbell bench press within this article, all of the issues I discuss also apply to the dumbbell bench press as well since the movements are largely the same. However, be sure to keep reading to learn why switching to the dumbbell bench press can help reduce shoulder pain under the right circumstances!

The good news is that arthritis of the shoulder isn’t overly common in young individuals, as it tends to become more common and problematic for those in their fourth, fifth, and sixth decade of life, becoming more common as we continue to age. So, if you’re a young, otherwise healthy individual without a history of nasty shoulder trauma, it’s unlikely that this is your specific issue.

What to do about this issue

If you’re more advanced in your years and the shoulder joint is arthritic, it may not appreciate experiencing large ranges of motion (such as when performing the Olympic lifts), so this may be a tricky situation to navigate. Activity modification may be required (such as using lighter loads), or foregoing the Olympic lifts altogether may be necessary. Nonetheless, arthritic joints need to stay moving; if you keep them from experiencing movement, they’ll break down at a quicker rate.

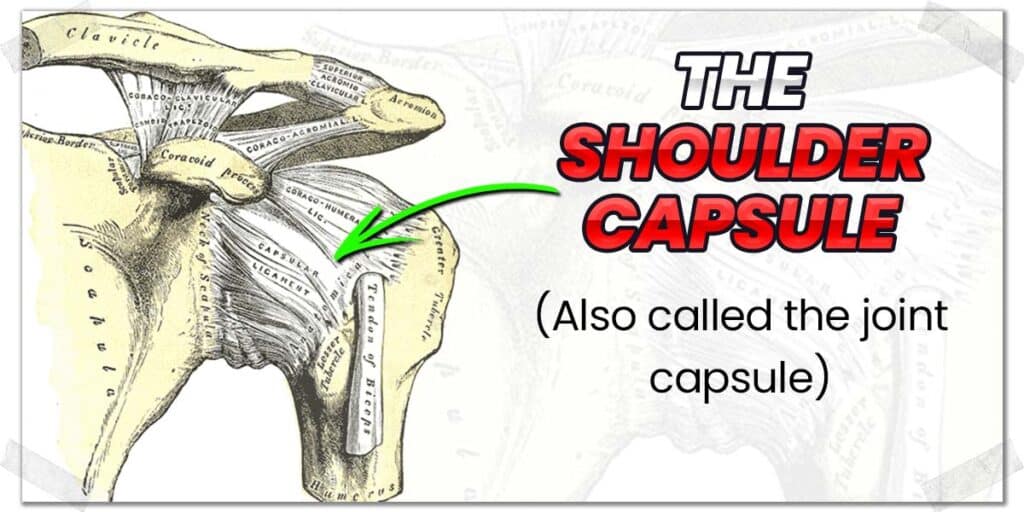

Pain generator 3: the joint capsule

The joint capsule of the shoulder is a thick, fibrous tissue that wraps around and covers the ball and socket portion of the shoulder joint.

Its role is to provide structural integrity to the joint while also housing synovial fluid within the joint, which acts to lubricate the joint in the same manner that engine oil lubricates the moving parts of an engine.

Regarding this capsular tissue, the most common issue to watch out for is adhesive capsulitis, otherwise known as frozen shoulder.

The shoulder capsule is prone to spontaneously becoming tight and painful in certain populations, particularly those who are in their fourth and fifth decade of life, and thus tends to occur more frequently in women than men (though plenty of men are still affected).

Pro tip: Though I will repeatedly mention the barbell bench press within this article, all of the issues I discuss also apply to the dumbbell bench press as well since the movements are largely the same. However, be sure to keep reading to learn why switching to the dumbbell bench press can help reduce shoulder pain under the right circumstances!

Frozen shoulder is usually a self-limiting issue, meaning you are allowed to do any activities you can tolerate while avoiding the ones that don’t feel all that great.

The challenge here is that frozen shoulders can often be quite painful or can drastically limit one’s range of motion in their shoulder. Oftentimes the individual will experience both.

What to do about this issue

If you want to read more about frozen shoulder, check out the following article of mine, which will serve as a primer and provide a few valuable resources:

Common shoulder issues when Olympic weightlifting

The Olympic lifts are more than just performing movements with explosive power; they are about explosive power that must be accompanied by optimal movement and technical finesse (in the shoulder and the rest of the body). Regarding the shoulder: this involves controlling its movement with ideal mechanics through an adequate range of motion while retaining stability throughout the entire process.

Lacking any of these three shoulder necessities will lead to a world of shoulder problems for anyone looking to perform the Olympic lifts, and since these are relatively common issues, we need to look at each one in a bit more detail.

Common issue 1: Poor shoulder mobility

One of the biggest issues I see when working with those learning the Olympic lifts (or rehabbing lifters in general) is poor shoulder mobility.

Poor shoulder mobility can arise for various reasons, but regardless of the underlying cause, the outcomes will be the same: dysfunctional (and often) and painful movement in or around the shoulder.

Routinely training the Olympic lifts without adequate shoulder joint mobility will turn your shoulder(s) into a ticking time bomb. Additionally, it will also compromise your overall lifting performance.

For most individuals, poor shoulder mobility results in the inability to raise the arms directly above their head (without arching their backs to compensate). The movement required to get the arms in this position is known as shoulder flexion, and a healthy shoulder should be able to obtain 180 degrees of this motion (going from arms by your side to directly above your head).

If you can’t get your arms directly above your head, you’ve got some work to do. Both the snatch and the jerk require a full 180 degrees of shoulder flexion so that you can catch the weight directly above your head; if your shoulders can’t make it into this position, you’ll be missing/failing a lot of your lifts and straining your shoulders in the process, or you’ll be compensating elsewhere in your body to make the lift (neither of which are good).

Improving shoulder mobility for the Olympic lifts

The first step in cleaning up and optimizing your shoulder mobility is to determine what’s causing it to move poorly. This is best done through an evaluation through a qualified healthcare practitioner, such as an orthopedic physical therapist.

If you don’t know what’s causing the problem, how will you know how to implement the solution?

In an otherwise healthy individual, the inability to raise the arm directly above your head (not caused by pain) can be the result of:

- muscular weakness (likely not the case in an active lifter);

- soft tissue restriction (tight muscles, fascial restriction, etc.);

- capsular restriction (a tight joint capsule);

- joint restriction (a restricted shoulder joint).

Solutions for improving your shoulder mobility will depend on the underlying cause, which I can’t cover within this article.

However, I have numerous other articles on this site that cover these topics in much greater detail. So, be sure to check out the following articles if you need more information.

- Frozen Shoulder & Working out: A How-to Guide (Detailed Article)

- Foam Rolling Your Pecs: A MUCH More Practical & Effective Way

Reading each article should provide you with an adequate primer for learning about what you’re up against and how to begin to regain mobility in and around your shoulder.

Common issue 2: Poor shoulder stability

The shoulder joint is a relatively unstable joint when compared to other joints, such as the elbow or the hip joint. The reason is that it sacrifices its stability to gain mobility. And while mobility is good, the more of it you have, the less stability you’ll have as well. It’s a direct trade-off.

Depending on the underlying cause of your shoulder instability, there are multiple approaches that may need to be considered. There are conservative measures (such as shoulder and rotator cuff strengthening routines) and invasive measures (surgery).

Surgical intervention is typically reserved for higher levels of instability and sometimes only after conservative measures have failed.

My guess would be that you’re not a surgical candidate if you haven’t had any major trauma to your shoulder in the past (car crash, nasty fall off a bike, etc.). Chances are, if you’ve already been Olympic lifting, you’re not dealing with nasty instability (though this is the internet, and I know nothing about you).

If you want to read up more on lifting with shoulder instability, check out my article: how to bench press with shoulder instability.

While it’s centred around bench pressing, many of the concepts are still the same with Olympic lifting. You’ll also learn a lot more about types of shoulder instability.

Common issue 3: Poor motor control

Motor control refers to our ability to volitionally control a movement we produce. In the context of this article, this volitional control is for the shoulder.

If the shoulder has ideal strength and mobility but lacks overall movement control during the Olympic lifts, it can lead to pain and dysfunction. It’s analogous to having a car with a powerful engine, good suspension, but sloppy or loose steering control.

The challenge with the Olympic lifts is that the movements are executed at such a fast, explosive rate that you don’t have time to think about how you’re moving your shoulders or coordinating your movement; these movements need to be automatic if you’re to have any hope with getting the weight above your head.

Naturally, your brain just figures out a way to move your shoulder and turns it into its default pattern, which could lead to pain or injury.

Examples of faulty shoulder mechanics for the Olympic lifts include:

- lacking upwards rotation of the shoulder blade during the overhead phase of each lift (commonly leading to shoulder impingement);

- Excessive shoulder protraction or retraction during any phase of the movement.

If your shoulder mechanics are off, you’ll need to clean them up. Sometimes, this is tough since you may not even know if (or how) your movement control needs to be addressed. For this, your best bet is to implement strategy 2 in the following section.

Universal strategies for improved shoulder health

Regardless of the specifics with your shoulder issue, there are universal strategies that every lifter should incorporate to ensure their shoulders become as healthy as possible.

These strategies should also be applied to those with healthy, pain-free shoulders to ensure shoulder maintenance. So, even after you’ve tackled your current shoulder issue, keep incorporating these strategies, if at all possible.

Strategy 1: Perform an elaborate shoulder & upper body warmup routine

Assuming you value the health of your shoulders, this is a non-negotiable. Without getting in the habit of implementing a proper and thorough shoulder warmup before each Olympic lifting session, you might as well start digging an early grave for your heavy or power-based lifting career.

Pro tip: Though I will repeatedly mention the barbell bench press within this article, all of the issues I discuss also apply to the dumbbell bench press as well since the movements are largely the same. However, be sure to keep reading to learn why switching to the dumbbell bench press can help reduce shoulder pain under the right circumstances!

There are numerous ways to effectively warmup your shoulder before a lifting session, which I’ve written additional content for here on this site.

Your best bet is to start with generalized movements and progress to specific movements.

Generalized movements include a dynamic warmup series, which will prep your entire body, then move into shoulder-specific movements and end with working warmup sets using the barbell.

Be sure to check out my article on the best equipment-free rotator cuff warmup protocol that you can possibly use if you want to use a warmup devised by a world-class expert.

An effective shoulder warmup should take a handful of minutes and should be part of an overall active dynamic warmup to ensure that your joints, muscles, tendons, and nervous system are all primed to deliver maximal performance while minimizing the risk of injury.

Strategy 2: Make sure your technique is on point (get a coach, etc.)

No matter how proficient you feel you are with your lifts, it’s worth hiring an experienced Olympic lifting coach, if possible. I used to train with numerous provincial and national Olympic lifting champions here in Canada, and here’s what they always said: it takes ten years of dedicated Olympic lifting training to get decent technique.

Granted, they hold their own technique (and the technique of others) to very high standards, but it serves its point; even these lifters who medaled on the national stage still had a coach evaluating their technique every night they trained at the club.

Not only does flawless technique make you a safer lifter, but it also makes you a better lifter in terms of how much weight you’ll be able to get over your head. So, get a coach who is qualified (preferably through a reputable association, such as with the NCCP designation), if possible, and you’ll stand a better chance of preventing shoulder issues from arising.

Final thoughts

The Olympic lifts are beautiful exercises and represent the epitome of strength, power, and technical finesse. However, due to their nature, they are incredibly demanding on the shoulder joint and surrounding tissues. As such, take the right precautions and steps to ensure you’re able to get any shoulder pain under control.

From there, make a concentrated effort to keep your shoulder health and its function as optimal as possible. If you do, you’ll prolong your days as a lifter, put up better numbers, and enjoy your lifting a lot more

Frequently Asked Questions

I’ve included this brief FAQ section to provide a few concise answers to other frequently asked questions regarding shoulders and Olympic lifting. I hope it provides more insight into any questions you may have!

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!