If you’ve been experiencing pain in your shoulder at the bottom range of your bench press, you’re not alone; it’s an issue that affects more lifters than you might realize. As such, this article will walk you through the common causes and solutions for this scenario, allowing you to have confidence in getting back to a pain-free bench press.

Shoulder pain at the bottom of the bench press can result from poor pectoral muscle mobility, biceps tendon or rotator cuff tendon issues, AJ joint issues, or capsule stiffness. Numerous solutions are available (discussed in this article) to remedy the issue.

Plenty of lifters choose to ignore the issue and “push through” their pain, but you’re a smart lifter, and you’re more interested in tackling the issue head-on, right? After all, lifters who get to the root of their pain have greater longevity when it comes to their years of lifting. And that’s something you’re into, right?

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

As we dive into the meat and potatoes of this article, please remember that an orthopedic evaluation from a qualified medical professional is always your best bet for resolving your issue. Also, keep in mind that I can’t cover everything within a single blog article; I’m only covering the more common shoulder issues that arise with this particular bench press scenario.

Alright, here we go!

Issue 1: Tightness or restriction in the pectoralis major

Let’s start off with an issue most lifters and active individuals have experienced at some point in their resistance training pursuits: tight pectoral muscles. It’s arguably the most common issue for this particular bench pressing situation, as the pectorals can become dysfunctional for a variety of reasons (training-induced or non-training-induced).

The pectoralis major is the primary muscle that’s trained during the bench press. It’s a muscle that most active individuals are familiar with, and unfortunately, it is prone to becoming tight, restricted, and otherwise painful during exercise. The reasons for this can be numerous, but common causes can include:

- poor posture with daily activities (leading to conditions such as upper-crossed syndrome);

- high training volumes (i.e., excessive amounts of chest exercises in a strength training routine);

- routinely training with excessively heavy loads for chest exercises.

Since the pectoralis major crosses the front of the shoulder and attaches to the upper portion of the humerus (the upper arm bone), it must stretch out to greater lengths as the bar is lowered closer to the chest during the bench press.

Therefore, if the muscle is already tight or restricted from optimal movement, it won’t tolerate moving into a stretched/lengthened position (i.e., as the bar is lowered closer to the chest).

Pro tip: Though I will repeatedly mention the barbell bench press within this article, all of the issues I discuss also apply to the dumbbell bench press as well since the movements are largely the same. However, be sure to keep reading to learn why switching to the dumbbell bench press can help reduce shoulder pain under the right circumstances!

Solution 1: Give your pectoral muscles some love

Healthy muscles are not only pain-free muscles but are also strong muscles as well. Therefore, any individual who takes their training seriously should carve out dedicated time within their week to perform techniques that can help keep their pectorals healthy and happy. However, this is especially true for anyone experiencing pain from tightness in their pectoral muscles when bench pressing. This can be done in the gym or at home (or even at both locations).

Of course, you can opt for professional treatment (massage therapy, physical therapy, etc.). However, if that’s not in the cards, there are a few simple yet rather effective self-treatment techniques you can try to improve pectoral mobility.

My favorite self-treatment technique (for a variety of reasons) is performing myofascial rolling, particularly for the pectoral tie-in region, which can be tricky to target if you aren’t quite sure what to do.

Thankfully, I have a detailed article (and video) going over how to achieve this, so if you want a very effective way to improve fascial mobility and tissue quality in your pectoralis muscle, check out this article here!

Solution 2: Consider using bands or chains, if possible

If you’re keen on pressing onwards (pun intended) with your bench pressing despite the bottom-range issues you’re experiencing with your shoulder, it might be worth performing your bench press with a dynamic resistance (an amount of resistance that changes throughout the lift).

If you have access (and the ability) to train with bands or chains for your bench press, you may find this to be a very helpful strategy. Using bands and chains on the bench press creates a dynamic resistance where the load is lightest at the bottom of the press (when the barbell is closest to your chest) and heaviest at the top. Notably, performing a dynamic-load bench press will likely still permit you to use challenging loads, so you won’t have to worry about losing notable gains in strength.

When experiencing pain at the bottom of the bench press: using bands and chains on the bench press creates a dynamic resistance where the load is lightest at the bottom of the press and heaviest at the top, which may help reduce this unwanted pain. Click to PostAgain, you’ll need to have access to some large resistance bands or chains, which isn’t available to every lifter, nor is it every lifter’s forte, either. Still, it can be a highly valuable training strategy to incorporate since it can still provide a hefty stimulus to your chest and triceps, albeit focused on the upper portion of the lift instead of the bottom.

Solution 3: Use boards or Bench Blokz

If bands or chains aren’t an option for you, you may want to opt for resting an object on your chest, which ensures you don’t go below a certain range during your press. It may sound unconventional, but it’s a very common technique in the competitive bench press world.

Granted, this technique is more often used as a means to enhance pressing strength with heavy loads than a pain avoidance strategy, but it will still be an outstanding intervention for allowing you to press while avoiding any shoulder pain during the press.

Most often, lifters will use 2×4 planks (typically, they have another lifter place and hold the board on their chest during the lift, but you can manage this by yourself). Whether it’s a single 2×4 or a couple (sometimes it helps to nail them together), for this pain avoidance scenario, it can be an effective training strategy. If you have a training partner, have them hold the board on your chest for you (but make sure they can still spot you, if needed).

If boards aren’t practical or too cumbersome for you, it may be worth picking up a Bench Blokz, which achieves the same effect as resting a board or two on your chest except that the Bench Blokz clips onto the barbell, so you don’t have to worry about anything sliding off your chest.

What’s even better, it can be clipped on in different orientations, allowing the block height to change the range of motion for your press, making it a versatile little object to have.

Issue 2: Tendon irritation in the long head of the biceps tendon

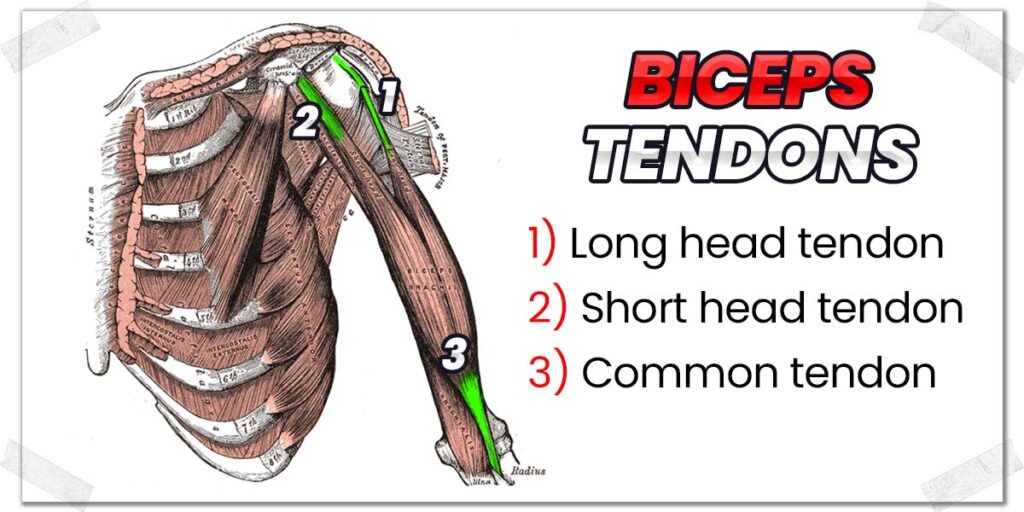

The biceps muscle has two individual muscle bellies or heads (bi = two), with each head having its own tendon up at the top of the shoulder (a tendon is what attaches a muscle to a bone).

One of those tendons, known as the tendon of the long head of the biceps, crosses the front of the shoulder joint (it attaches to the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, for those who are wondering).

This tendon undergoes a notable stretch any time the shoulder joint is extended (moves the upper arm backwards).

As such, if the tendon is irritated or in an otherwise unhealthy state, shoulder movements (such as lowering the barbell closer to your chest during the bench press) can cause shoulder pain.

If your shoulder pain is due to the biceps tendon being irritated or unhealthy, this is why you likely experience the greatest amount of pain or discomfort at the bottom range of the movement; this is the position that places the greatest amount of stretch onto the tendon.

Solutions for biceps tendon issues

If your biceps tendon is giving you grief, simply trying to push through the pain won’t work. Instead, you’ll want to:

- Alter your range of motion (for the time being) when benching.

- Perform some gentle range of motion exercises for the muscle and tendon.

- Perform targeted loading exercises to stimulate the tendon back to fill health.

Let’s look at each of these strategies in a bit more detail.

Modifying your range of motion

Since irritated tendons do not appreciate aggressive stretching, and since the long head of the biceps tendon receives its greatest stretch at the bottom of the bench press (i.e., when the bar is on your chest), modifying your range of motion (for the time being) can be a smart step to take.

Essentially, staying out of any pain-provoking ranges of your bench press will ensure your biceps tendon doesn’t repeatedly get provoked each time you lower and raise the bar. This is the same concept as with tight pectoral muscles.

It can sound blasphemous to some lifters to not bring the bar all the way down to their chest, but it’s the right move to temporarily make if your tendon is lit up. Your other option is to use chains or bands (discussed in issue 1) to offload the bottom portion of your bench press, which may spare the tendon excessive stress or strain when lengthened at the bottom of the press.

Additionally, as mentioned earlier in the article, when dealing with pectoral tightness, you can also consider bench pressing with some boards on your chest (i.e., consider doing board presses) or using the Bench Blokz. Either of these will help keep you in more moderate ranges that don’t further provoke the biceps tendon with aggressive lengthening into the bottom of the press.

Performing gentle tissue mobilization for the biceps

While biceps tendon irritation will require its own direct treatment intervention, it can still be helpful to give some treatment to the remainder of the biceps muscle itself. Doing so can potentially help reduce any excessive tension resting in the muscle that may create tension in the tendon.

There are two simple treatment techniques that I often use with patients for this scenario:

Treatment 1: Voodoo flossing for the elbow

Voodoo flossing (often called compression flossing or tack and floss) is a treatment technique that can be quite helpful for improving tissue mobility within the body. In the case of your biceps muscle, flossing can help improve your range of motion at the elbow (where the biceps attaches), which may help offload excessive tension that might otherwise be experienced in the long head of the biceps tendon.

If you want the specifics, check out my article on how to voodoo floss your elbow, where I provide a detailed walkthrough (including my YouTube video with step-by-step instructions).

Treatment 2: Gentle biceps stretch

Stretching irritated tissue (such as tendons) needs to be done cautiously, but if done correctly, it can usually have therapeutic benefits. The key is to keep any stretches on the gentle side and perform them with a high frequency (multiple times throughout each day).

A therapeutic biceps stretch I sometimes give my patients involves making a fist and then placing it in a door frame or against a wall and then gently straightening the arm to stretch the biceps muscle (see the photo below).

The more irritated your biceps tendon is, the more gentle this stretch needs to be.

For a highly irritated biceps tendon, simply lengthen it to the point where you begin to feel a very mild stretch (it should almost feel like you’re not doing anything at all). I like to hold the stretch for a few seconds, then take a break for a few seconds, and then repeat for fifteen or twenty times.

Using loading exercises for tendinosis

It’s not uncommon, by any means, for active individuals and those who use their shoulders a lot to experience biceps tendon issues, most notably tendinosis.

Tendinosis is a very common disorder that compromises the structure and function of a tendon, reducing its overall health.

Related content:

Overcoming tendinosis and restoring the tendon back to full health and function is best done through loading exercises (exercises that involve mechanically stimulating the tendon through resistance exercises).

I’ve got an entire article on loading exercises for biceps tendon issues, so be sure to check it out if you want all the specifics on how to perform effective loading to overcome this stubborn and annoying issue.

Issue 3: Subscapularis tendinosis

The subscapularis muscle is one of the four muscles that comprise the rotator cuff. It attaches to the underside of the shoulder blade and to the upper portion of the humerus bone, right next to the long head of the biceps tendon.

This insertion point, just like the long head of the biceps tendon, can become sore and unhealthy, leading to tendinitis and tendinosis of the subscapularis tendon.

Pro tip: The subscapularis muscle can often become tight or have trigger points within the muscle belly, which can also cause pain and dysfunction within the shoulder.

Take your rotator cuff health seriously. Without healthy rotator cuff muscles, you’re bound to experience a lot of painful bench pressing and lousy performance during the bench press (in addition to plenty of other upper body exercises as well).

The best strategy for improving the health and function of the subscapularis muscle and tendon is to – as with the long head of the biceps tendon – mechanically stimulate it with an appropriate loading protocol.

I’ve got a detailed article detailing the best subscapularis strengthening exercise you can possibly do, so be sure to check it out if you want to learn how to perform the kinetic medial rotation test exercise, which very few people on the internet seem to be talking about.

Issue 4: AC joint hypomobility

The acromioclavicular joint (the AC joint) is the joint that forms between the end of your collarbone (the clavicle) and the acromion process of the shoulder blade (the scapula). While it doesn’t have anywhere near the available movement as the shoulder joint, it still needs to move a bit to achieve optimal, pain-free function when the shoulder and arm are moved.

Unfortunately, as with any other joint in the body, the AC joint can become stiff (for various reasons) and therefore become painful when subjected to more extreme ranges of motion.

As with the strategies mentioned earlier involving tight pectoral muscles and irritated biceps tendons, you’ll likely do well to shorten your range of motion during the press, either with physical barriers (2x4s or Bench Blokz) or but simply keeping the barbell out of the painful rage of your press without using any barriers.

Still, there can be two other strategies unique to the AC joint that can be helpful for shoulder issues at the bottom of your bench press. Let’s briefly look at each of them below.

Strategy 1: Changing the grip width of your bench press

The width of your bench press grip can significantly influence the stress the AJ joint undergoes, largely due to the larger or smaller ranges of motion that it creates.

A narrow grip leads to further range of motion of the shoulder joint for the bench press, which can place further stress on the AJ joint. Conversely, a wider grip shortens the range of motion, lessening the AJ joint’s stress.

As such, if you’re using a strictly shoulder-width grip (which can have its advantages at times), it may be worth increasing your grip width on the bar. A grip width wider than your shoulders may be less stressful and, therefore, irritating on the AJ joint.

However, be sure not to go excessively wide; too wide of a grip can increase strain on the pectoral muscles or the front of the shoulder joint, creating its own separate set of issues.

Strategy 2: Switching to the dumbbell press

If increasing your grip width doesn’t produce any appreciable change for your AC joint issue, you’ll likely appreciate how the joint feels when switching over to the dumbbell bench press.

The dumbbell bench press is often less taxing on the AC joint since each arm can move into a slightly different position than when grabbing onto a barbell. The result is different positioning of the upper arm bone (the humerus) and less stress on the AC joint.

There’s room to play around with exact arm and wrist positioning when performing the dumbbell press, so feel free to tinker around to find what works best for you and your shoulder(s). Just find what takes the stress off your joint and press in that position for the time being (until you get the underlying cause addressed).

Pro tip: A stiff AJ joint is hard to treat on your own, but thankfully it’s usually quite straightforward to treat with help from a qualified professional. The joint often responds quite favorably to manual therapy (joint mobilization) with just one or two treatments.

Issue 5: Shoulder capsule stiffness

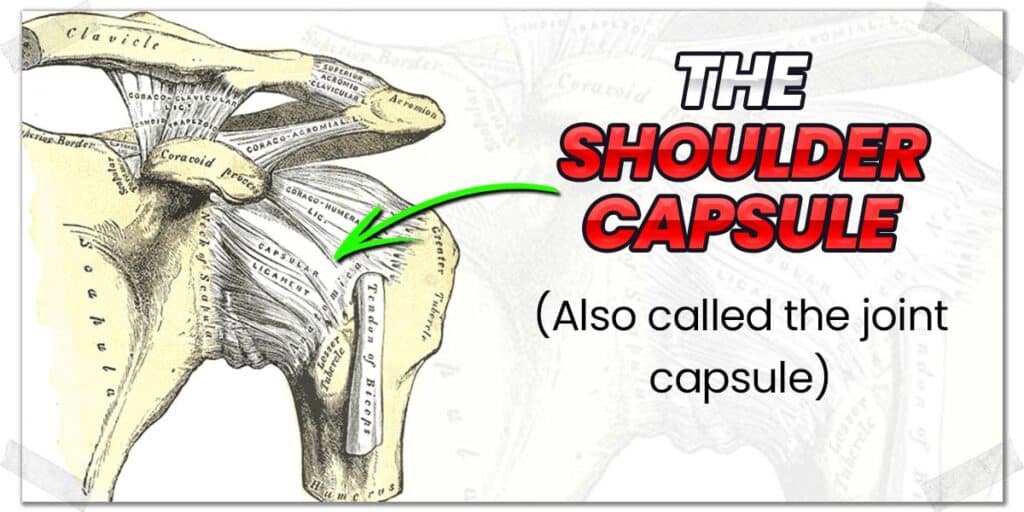

The shoulder capsule refers to the thick, leather-like tissue that wraps around the ball and socket joint of the shoulder. It provides structural reinforcement to the joint while also housing the fluid (synovial fluid) within it, which acts as a lubricant to its surfaces (the cartilage).

Unfortunately, the shoulder capsule can become stiff and immobile (often for unknown reasons), leading to reduced shoulder mobility and pain.

The condition is known as adhesive capsulitis but is more commonly referred to as frozen shoulder. It can arise after prolonged shoulder immobilization (such as keeping your shoulder in a sling for weeks on end) or seemingly out of nowhere.

When it arises for unknown reasons, it’s known as a primary frozen shoulder, and most often does so in the fourth and fifth decades of life. (I started getting mine, however, in my late thirties). I know plenty of lifters who have had to deal with this issue, including myself.

Frozen shoulder can be an annoying issue to work through, particularly when it comes to trying to continue to work out and exercise, but thankfully, it’s a self-limiting condition, meaning you can likely do any activities you want so long as it doesn’t worsen your pain.

I’ve got a very detailed blog article going over all the essentials on how to workout with a frozen shoulder, so head over to that article if you want practical and effective information on dealing with this condition.

Final thoughts

Experiencing shoulder pain or discomfort at the bottom of the bench press is surprisingly common, especially for those with a history of shoulder issues or those undergoing high volumes of intense resistance training. Thankfully, if addressed early, the issue can often be rectified quickly, allowing one’s training to resume as normal.

Don’t try to ignore what your body is telling you; if something is painful, something’s not right. Take the time required to get to the root of the issue, then work on addressing the underlying cause. Your body will thank you, and so will your bench press.

Frequently asked questions

I’ve included a few brief answers to some frequently asked questions regarding bench press and range of motion during the exercise. I hope they can help with any additional questions you may have about this topic!

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!