The bench press is one of the classic lifts that reigns king for developing upper body strength; it not only strengthens your pecs but your triceps and shoulders as well. But if you suffer from shoulder instability, bench press might be a tricky, frustrating — or even painful — exercise for you to try. So, sit back and read through this article; I’ve got you covered on what you need to know to start going about this whole ordeal.

Bench pressing with shoulder instability requires knowledge about your type of instability (typically anterior or posterior), strengthening the muscles of the shoulder (primarily the rotator cuff) and optimizing range and arm positioning when benching to ensure maximal stability.

Now, to be clear, there’s more to it than that; what’s described above is merely the general synopsis. The ticket to success is in the details. So, if you want to learn why specific actions must be taken, which muscles must be targeted, and which types of grip and bench press variations you’ll likely need to perform, keep on reading.

As we dive into this article, please keep in mind that I don’t know anything about your personal shoulder situation. As such, please consider getting a shoulder assessment from a qualified healthcare professional. What follows below is for informational purposes only.

Quick note: Depending on the nature and severity of your shoulder instability, it may be required for you to avoid bench pressing and similar exercises for the time being; a highly unstable or painful shoulder may only tolerate smaller, lighter shoulder and arm exercises in the early stages of rehab. Much of what follows below is intended for individuals who are deemed non-surgical candidates; individuals with high levels of instability or pain may require surgery and may want to avoid bench press until further consultation with a qualified medical specialist.

Shoulder instability explained

If you want the best chance possible at learning to bench with an unstable shoulder joint, it’s imperative you understand the basic anatomy of the shoulder joint along with the general causes and presentations of instability. If you do, you’ll be much less likely to make costly mistakes and waste precious time attacking the issue.

Additionally, taking the right actions and performing effective exercises will become much more intuitive. So, let’s start attacking this beast!

Types & causes of shoulder instability

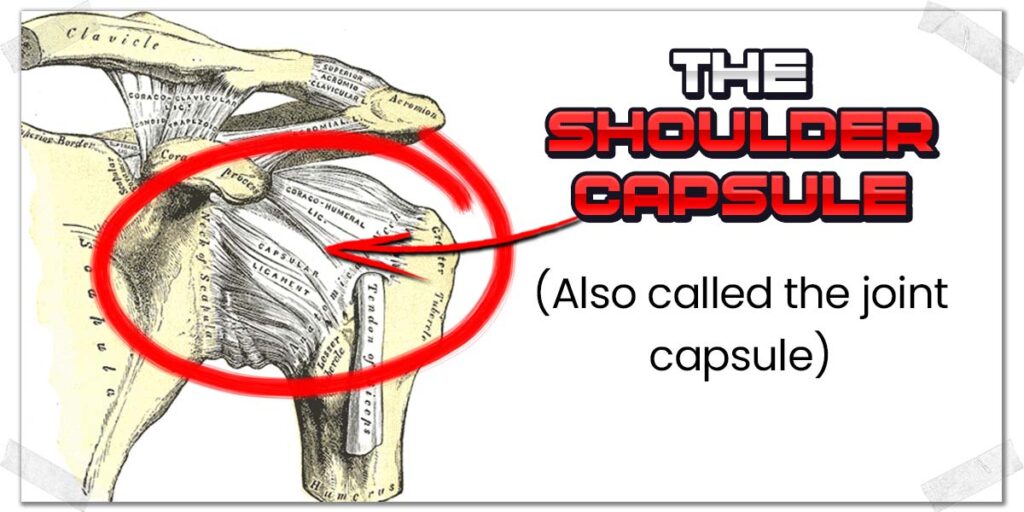

Shoulders can become unstable for different reasons, however, most of the time, it’s due to trauma to the joint. Shoulder dislocations are a prime example of this. When excessive force gets put through the shoulder joint (such as with dislocation or subluxation), the joint capsule (the thick, fibrous tissue that covers the ball and socket joint) can become overly stretched, which compromises the joint’s integrity.

This is probably a good time to quickly run through the very basic anatomy of the shoulder.

Basic shoulder anatomy

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint, which allows it to freely move in any direction. The shoulder joint itself is anatomically referred to as the glenohumeral joint. For the sake of this article, however, I’ll just refer to it as the shoulder joint.

A great deal of the shoulder’s inherent stability comes from the fibrous tissue that wraps around the ball and socket joint, which, as mentioned above, is collectively known as the joint capsule.

The outer portion of this joint capsule consists of ligaments that are “woven into” the capsule. These ligaments act as thick, fibrous bands that connect the shoulder blade’s socket (the glenoid) to the head of the humerus (the upper arm bone). These ligaments provide the joint with its inherent stability and are naturally rather taught and snug in an otherwise healthy shoulder.

“Training your rotator cuff is the starting point in this whole shoulder instability ordeal. Typically, you’ll want to start by working on maximizing the co-contraction of these muscles”

– Strength Resurgence

When these ligaments become overstretched (typically from trauma, such as a fall or crash), they have very little ability to naturally tighten back up on their own, which is where individuals can run into stability issues when performing physical activities, such as when benching.

Anatomy fact: The more available range of motion a joint has (the more it can freely move), the more unstable it naturally becomes. Since the shoulder joint is naturally very mobile, it is more prone to becoming unstable than other joints in the body with less natural mobility.

Thankfully, even when these ligaments are compromised, joint stability can still be improved by implementing specific exercises and incorporating training strategies for the muscles that cross over the shoulder joint (more on that later).

For now, let’s look at the two most common types of shoulder stability that can arise. Read through each one to see if you can better determine which type of instability you may have.

Types of instability: TUBS & AMBRI

Without going into the anatomy weeds here, two primary classifications tend to be used within the physical therapy world to describe an unstable shoulder. The specifics aren’t all that important for you; rather, just having a general concept of each should suffice for you. In the following sections, I’ll be breaking down both types of instability.

TUBS instability

TUBS is an acronym for describing a particular type of shoulder instability. It stands for:

Traumatic onset, Unidirectional, Bankhart, Surgery

As the name implies, it results from a forceful (traumatic) injury that causes the shoulder joint to become unstable. By nature, the resulting instability in the shoulder joint is typically multidirectional (the instability occurs in all directions). The term bankhart refers to a specific type of lesion to the labrum (a cartilage ring around the glenoid). It typically requires surgery to fix, as non-operative treatment has less than a 20% success rate, at least according to the literature I’ve looked at.

Since you’re interested (and are already likely making attempts) at bench pressing, I’m assuming you do not fall into this category of shoulder instability. That being said, I can’t be certain, so if you’ve had a recent traumatic injury to the shoulder (or have a history of traumatic shoulder injuries), getting a proper shoulder evaluation is certainly advised.

AMBRI Instability

AMBRI is the second category of generalized shoulder instability. This acronym stands for:

Atraumatic onset, Multidirectional, Bilateral, Rehabilitation, Inferior capsular shift

It can occur from either a previous history of shoulder injuries (typically one or multiple dislocations), a shallow glenoid fossa (something you’d be born with), a labral tear, or from having excessive joint mobility throughout your body, such as when having Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

This type of shoulder instability is typically described as feeling like the shoulder wants to “pop out” with larger ranges of motion. It may present with mild or moderate pain as well.

“The wider your grip, the greater amount of external rotation your shoulder will need to undergo, which will likely cause pain and instability. Research has shown that using a grip-width greater than 1.5x the length of your collarbone (biacromial) during bench press can lead to greater chances of shoulder instability and subsequent injury.”

-Strength Resurgence

Assuming your shoulder instability has been more of a longstanding issue, hasn’t recently become worse, isn’t painful, and is otherwise controlled, a generalized conservative approach towards strengthening your shoulder muscles while avoiding large or vulnerable ranges of motion, for the time being, is likely an ideal starting point.

If you’ve been bench pressing without any major issues recently, you can likely implement the solutions below. But, again, if you aren’t certain about your overall shoulder status, consider getting an evaluation (I gotta cover my butt here, ya know?).

Vulnerable shoulder positions with bench press

When attempting to bench press with an unstable shoulder, lifters tend to feel most vulnerable in one of two positions, depending on the type of instability they have. Keep in mind, though, that this is not a hard and fast rule.

Anterior shoulder instability

When the front side of the shoulder joint is unstable, most lifters will often feel the most unstable or “vulnerable” towards the bottom range of the bench press (when the weight is closest to the chest). This is mainly due to the position that the glenohumeral joint is forced into when performing the press; the head of the humerus is forced to translate forwards, particularly if you have your elbows flared out quite wide (pointing in opposite directions from one another). This will be covered in more detail below. Anterior shoulder instability is by far the most common type of shoulder instability, with approximately 98% of all instability cases occurring anteriorly.1

Posterior shoulder instability

Posterior instability refers to the backside of the shoulder joint being unstable. The greatest amount of stress placed on the posterior aspect (backside) of the shoulder capsule occurs at the top or start of the bench press position.

In this position, the force of the weight you’re holding travels straight down the arm, pushing the humeral head directly towards the floor. If the shoulder joint is loose, you may feel discomfort in the area, or in cases of excessive instability, you may even feel the head of your humerus sliding backwards (towards the floor).

Thankfully, nonsurgical treatment of posterior shoulder instability has high levels of success.2

whether you have more anterior or posterior instability, many of the tips and strategies listed below will be a practical start for helping to regain some stability and control of your shoulder.

Solutions for shoulder instability when benching

Assuming you’re not a surgical candidate, there will be multiple actions to start taking to improve your shoulder stability for bench press. Below are the generalized principles typically required for an unstable shoulder that will not have any surgical intervention.

Additionally, for any of the solutions mentioned below, ensure that you’re always performing your exercises, bench press variations, etc., with a slow tempo. Improving shoulder stability and control will be hard to come by if you’re using fast movements.

Ideally, try to go slow enough on every exercise and movement so that you can explicitly concentrate on (and feel) what your shoulder is telling you. There’s no need to go fast on any of these movements. Save the faster/normal tempo training for when you feel/know your shoulder stability is no longer an issue.

Training the rotator cuff

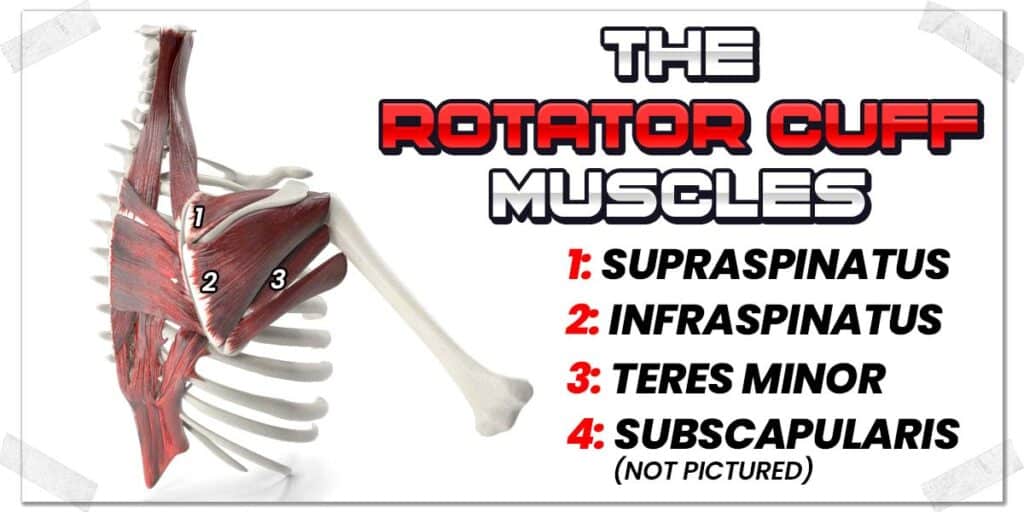

The rotator cuff refers to a group of four specific muscles that cross the shoulder joint. Collectively, they work to help fine-tune shoulder movements while also providing additional stability to the shoulder joint itself. These four muscles are:

- The supraspinatus

- The infraspinatus

- The subscapularis

- The teres minor

While these aren’t the powerhouse muscles of the shoulder region (those muscles are ones such as the deltoid, the pectoralis major, and the latissimus dorsi), they are of immense importance for ensuring proper shoulder mechanics and shoulder stability.

For atraumatic (no-trauma involved) shoulder instability, one study by Rowe and Zarins involving 47 patients, 80% of them reported excellent or good results with a program that emphasized progressive strengthening of the rotator cuff and other scapular-stabilizing muscles.3

As such, it is imperative that you work on improving (and, after that, maintaining) the health and strength of these rotator cuff muscles.

Related content:

Training your rotator cuff is the starting point in this whole shoulder instability ordeal. Typically, you’ll want to start by working on maximizing the co-contraction of these muscles (more on that in the following section).

There are a million-and-a-half rotator cuff exercises that can be done, including co-contraction exercises. While I can’t cover all of them, I’ll provide you with some insight into some introductory ones potentially worth trying.

Co-contraction of the shoulder muscles

One of the concepts you’ll need to become familiar with for improving your shoulder stability is co-contraction of your shoulder, as it has been shown reestablish dynamic joint stability of the shoulder.4 Co-contraction refers to the muscle groups that cross a joint contracting simultaneously to essentially “clamp down” on the joint for a bracing effect. The greater the extent of co-contraction taking place, the greater stability the joint will have.

But co-contraction consists of more than just doing so while the joint is motionless. You’ll need to learn how to modulate this co-contraction in a way that keeps specific muscles active enough to provide stability while simultaneously moving your shoulder while benching (or when performing other exercises, for that matter).

It will likely take some practice to get good at co-contracting your shoulder muscles, both statically and in a controlled manner with movement. The payoff is absolutely worth it, though.

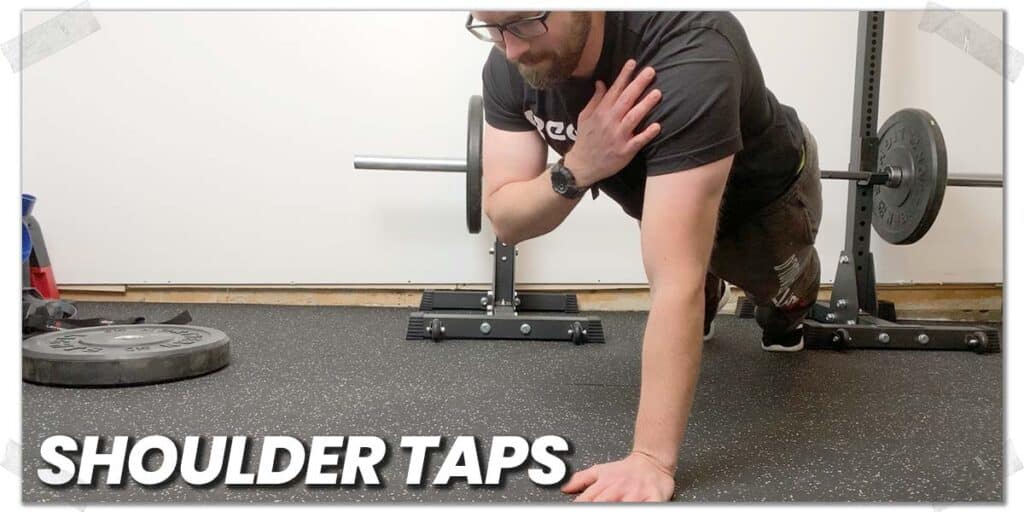

In a study by Richard et al., closed-chain exercises (an exercise where the hand is in contact with the ground or wall) were shown to activate surrounding muscles of the shoulder joint through co-contraction.4

Some of my favorite static co-contraction exercises for mild to moderately unstable (but otherwise healthy) shoulders are:

- Plank shoulder taps (either on the floor or against the wall)

- Clock sweeps against the wall

- Dumbbell arm bars (lying on the ground)

Take some time to explore some rotator cuff exercises that will challenge the strength and stability of your shoulder. From there, get into the habit of performing a shoulder routine at least a few times a week to improve not only the strength of your shoulder muscles but your ability to control them as well.

Changing up your grip

A critical concept to understand when bench pressing is that the type of grip positioning you use can dramatically influence how the shoulder joint behaves. Let’s look at this in more detail.

When bench pressing, the standard barbell grip requires the forearm to be in a pronated position (your palms facing away from you). As a result, your upper arm bone (the humerus) must move into more of an abducted position, which refers to your upper arm bone (the humerus) being raised out to the side.

The wider your grip, the greater amount of external rotation your shoulder will need to undergo, which will likely cause pain and instability. Research has shown that using a grip-width greater than 1.5x the length of your collarbone (biacromial) during bench press can lead to greater chances of shoulder instability and subsequent injury.5

Shoulder abduction can place a shoulder with anterior instability in a rather vulnerable position. When in this position, it can become even more vulnerable the lower you bring the barbell to your chest – especially with a rather wide grip.

As such, if you’re finding your shoulder to feel physically vulnerable, or you’re not mentally comfortable with the position it’s moving into, you may want to ditch the standard barbell bench press (at least for the time being) and opt for variations of the bench press that allow you to use a neutral or semi-neutral grip.

If nothing else, you can try narrowing your grip-width and reducing your elbow flare, meaning you keep your elbows closer to the sides of your body. This will reduce the extent of abduction your shoulder is exposed to, which should help reduce the overall forward translation of the humeral head in the socket as you lower the weight toward your chest.

Most lifters I’ve come across who have anterior shoulder joint instability feel much safer overall when bench pressing with a neutral or semi-neutral grip and keeping their elbows tucked in a bit more.

Pro tip: If you’re not willing to deviate from using a barbell or don’t have any dumbbells to switch over to, consider narrowing your grip to just slightly wider than shoulder width (if you’re not already using this width to begin with). A barbell grip wider than this will likely only place further stress on the front of the shoulder joint.

Benefits of the neutral grip

Unlike the traditional barbell grip, a neutral grip will drastically reduce the amount of abduction that your shoulder joint will need to move into during the press.

Less shoulder abduction during the bench press equates to greater shoulder joint stability (and perhaps less pain) throughout the press.

Does this mean you’ll need to avoid the standard barbell press forever? Not necessarily. As time goes on, if you get good at co-contraction around your shoulder and exhibit exceptional bar path control, you might be able to do barbell benching.

Still, if you’re not competing in bench press or in powerlifting, you can still build an exceptionally powerful bench press without using a traditional barbell.

Pro tip: The neutral-grip bench press will place a greater emphasis on the triceps muscles than the traditional barbell bench press, but don’t worry; your pec muscles and anterior deltoid (shoulder) muscles will still be getting adequate stimulation as well.

Dumbbells and Swiss bars

In order to keep your grip to a neutral or semi-neutral position when benching, your two best options are:

- Dumbbells

- The Swiss bar

Dumbbells likely take the cake for the best alternative as they’re typically the most accessible to lifters. Additionally, you can fine-tune the exact grip angle that you use, going from an entirely neutral grip to a near-overhand grip and anything in between.

The Swiss bar is also an outstanding alternative, although you’ll have to have access to one (typical public gyms are less likely to have them, whereas powerlifting-friendly gyms will likely have one). The Swiss barbell usually has different angles at which you can grip its handles, again making it an outstanding bar for bench pressing with when you have shoulder instability.

Starting with smaller ranges of motion

If you’re prone to experiencing shoulder instability or are apprehensive about it when you’re benching, a smart move to make is to ensure you optimize your range of motion during the press for which your shoulder can tolerate. This is a wise move to make in your initial stability improvement stages, even if you’re otherwise confident about your shoulder movement and range of motion.

With anterior shoulder instability, the lower you bring the bar to your chest during the bench press, the greater the amount of shoulder instability you’ll likely experience.

As such, sticking with a smaller range of motion (i.e., not bringing the bar down to your chest) might be a smart move, at least initially.

Pro tip: If you need to stick with this range of motion for a while, you can consider using bench boards or BenchBlox to ensure you’re not bringing the bar down too low towards your chest.

As time goes on, and you learn to have maximal shoulder control within the smaller, upper ranges you’re working in, you could consider increasing the range of motion and mastering control in a now expanded (but likely not yet full) range of motion. Once you have taken adequate time and training sessions to master this range of motion, you could then consider expanding your range (bringing the bar lower) even more.

Strengthening your shoulder in smaller ranges of motion will not only allow you to work on maximizing your shoulder stability, but it will likely also improve your overall confidence with your shoulder during the bench press.

Try these types of bench press variations

In addition to training your rotator cuff muscles, switching to a neutral grip, and working on controlled ranges of motion, you may want to consider the following bench press variations. Each of them offers unique benefits.

You can also consider implementing any of the following bench press variations with the previous strategies mentioned above, as the following exercise variations can be utilized with different grips, ranges of motion, etc.

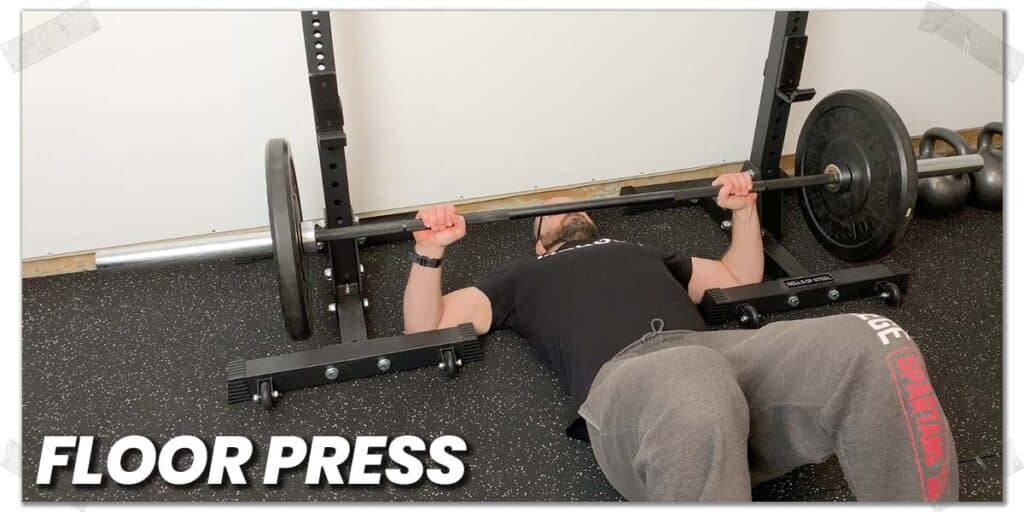

Utilizing the floor press

If you’re in need of ensuring you stay within a limited range of motion during your press (and you want to build some seriously strong triceps in the process), you could consider implementing the floor press (either barbell or dumbbell) into your regimen.

The floor press is essentially the bench press exercise, except it’s performed while lying on the ground instead of on a bench. This confines the lifter’s range of motion to the upper half of the pressing movement.

The floor press is a tried and true exercise that is absolutely worthy of performing even if you have perfectly stable and healthy shoulders. It will place a strong emphasis on your triceps strength while likely keeping your shoulder in safer positions and ranges.

Personally, I’d stick with floor pressing for the first couple of months until I was absolutely confident in my shoulder’s ability to remain stable throughout an upper-body pressing movement.

Try using the Smith machine

Bench pressing on the Smith machine is often shunned by hardcore lifters. However, if you have an unstable shoulder or need to rehab your shoulder as you progress back to free weight benching, the Smith machine can be your best friend (any lifter who has had to rehab their shoulder can attest to this).

Performing the bench press on the Smith machine will allow you to train the bench pressing motion while not having to worry about the barbell moving freely in all directions. Since the bar will be on a guided track throughout the press, you’ll be able to focus a bit more of your mental energy and physical effort on controlling the bar downwards and pressing it up without the need for controlling the bar in any other direction.

While some lifters don’t like the feeling of the bar being on a guided track (it does tend to create a slightly unnatural bar path), you likely won’t be testing your maximal strength or performing rather heavy benching on the Smith machine, so it really shouldn’t be an issue.

The name of the game here is to have some guided control as you concentrate more on your shoulder stability; think of it like riding a bike with training wheels; it keeps you a bit safer as you work to improve the quality of your movement and control.

Related content:

Performing the decline bench press

Another great bench press variation to consider (either with a barbell or dumbbells) is the decline bench press.

Unlike the traditional flat bench press or incline press, the decline press will actually place your shoulders in what’s likely a less vulnerable position (particularly if you have anterior shoulder instability).

The reason is that the decline bench press requires less external rotation of your shoulder joint when lowering the weight downwards towards your chest.

Pro tip: You’ll likely want to avoid incline press until you have high levels of stability and confidence with your shoulder; incline press places the shoulder in a more externally rotated position than flat bench press or decline bench press, meaning it has a greater likelihood of inducing shoulder instability.5

Additionally, you could consider performing the decline press using a Swiss bar or a set of dumbbells with a neutral grip. Either of these would likely allow you to keep your shoulders in a less provocative/compromising position due to using a neutral hand position.

Final thoughts

Shoulder instability can be frustrating to deal with, and it can truly affect physical (and mental) performance on exercises like the bench press. Thankfully, if your shoulder isn’t to the point where it requires surgery, you can likely improve the overall control and stability of your shoulder during bench press, provided you put some dedicated time and effort into doing so while also making the appropriate adjustments to the exercise.

Lastly, never be afraid of getting a shoulder examination by a qualified healthcare professional; they will be able to give you specifics about your shoulder that I can’t do within a blog article. From there, set some goals for yourself with getting over this shoulder issue and go make some good things happen!

References:

3. Rowe CR, Zarins B. Recurrent transient subluxation of the shoulder. JBJS. 1981;63(6):863-872.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!