There are a lot of people on the internet who want to know if pistol squats are bad for their knees and why they sometimes cause knee pain. If this happens to be you – or you happen to have knee pain with pistol squats – read this article; I will be detailing what you need to know about this often misunderstood exercise, including cleaning up your pain by optimizing your technique. I’ll also discuss how to modify, progress or regress the movement itself to best suit your needs and abilities.

The most common reason for knee pain with pistol squats is high levels of mechanical stress placed on the muscles and tendons crossing the knee throughout the movement, combined with poor motor control and subsequent knee joint positioning during the movement. Other factors can also exist.

So, if you want to know whether or not pistol squats may or may not be a good idea for you and how you can tweak and fine-tune them to make them work for you sans pain, keep on reading. After all, who doesn’t want a set of bulletproof knees?

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any exercises mentioned in this post may or may not be appropriate for you, including pistol squats. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

Related content:

So, are pistol squats good or bad?

Certain movements and exercises (such as pistol squats, in this case) are much like pharmaceutical medicine: different medications are appropriate for different people based on what their bodies need and can tolerate. And, even when the medication is appropriate, the dosage needs to be just right.

Too little of a dosage and you won’t get the desired effects; too great of a dosage and you now have something too potent, which leads to a new set of problems.

It’s important, therefore, not to blindly nor ignorantly jump to conclusions about whether or not pistol squats are “good” or “bad” in a universal sense. Rather, knowing the demands of the movement and how it can go wrong can help people know whether or not it may be an appropriate movement for them.

Seafood can be a healthy food choice for some, while it can be devastating for those who are allergic to it. Pistol squats can be thought of in the same light; they’re awesome for some people and not for others.

Essentially, there’s little room for error here throughout the entirety of this movement. Forcing your knee to achieve high levels of stability while simultaneously having to deal with a relatively high load to maintain and control throughout an extensive range of motion is asking a lot of the joint.

It’s kind of like asking someone to solve a math problem in their head while they run a 200-meter sprint as quickly as possible; it’s doable, but it’s a greater challenge than when afforded the ability to purely focus on one at a time.

Common causes of knee pain when pistol squatting

As we start off here, keep in mind that knee pain is often multifactorial (meaning the pain is concurrently driven by more than one single issue). However, for clarity and conciseness within this article, I will be presenting the common pain mechanisms one by one. Also, I can’t cover every possible issue (I’m not mentioning bursal issues such as pes anserine bursitis, fat pad syndrome, previous meniscal injuries, etc.), so keep that in mind; I’m tackling the low-hanging fruit that tends to affect the masses.

Cause 1: Inadequate tissue health and tendon overload

If you don’t have knee pain when performing double-leg squats (or other double-leg exercises) but seem to have pain with single-leg squat variations (such as lunges, Bulgarian split squats or pistol squats), the pain mechanism presenting itself within or around your knee could be due to inadequate tissue health.

Pistol squats demand the tendons of the involved knee to take on a full bodyweight load throughout the movement. As a result, the quadriceps tendon and the patellar tendon, which are comprised of a sort of thick, gristly tissue, can elicit pain if either the load (i.e. the body weight) is too demanding or if the tendons are in a mildly unhealthy state, consisting of tendinosis (a generalized lack of tendon health).

Even if the tendons around the knee are otherwise healthy, they can still be irritated by pistol squats if they’re unaccustomed to the demands of the movement. The same holds true for experiencing knee pain with leg extensions or knee pain with hamstring curls, which I’ve written detailed articles on to help you overcome such annoying issues.

Either way, tendon pain is a common pain mechanism in many active individuals, as tendon issues are prevalent in a high percentage of individuals. Keep on reading if you want to learn how to effectively deal with and overcome this issue.

Cause 2: Large or excessive ranges of motion

A second factor unique to pistol squats that contributes to tendon-based discomfort is the range of motion to which the tendons are subjected. Generally speaking, forcing tendons to contract out of extremely lengthened positions (such as the bottom of a pistol squat) requires those tendons to endure very high levels of stress from the contracting muscle(s).

The more unhealthy a tendon is, the more sensitive (and perhaps, irritated) it will likely be to:

- Being stretched

- Having to endure the stress associated with its respective muscle(s) pulling it out of its lengthened position.

The easy solution here (assuming you only have knee pain when undergoing larger ranges of motion) is to either:

- Shorten your range of motion for the time being.

- Decrease the overall resistance or load on your knee while using the same range of motion.

Regardless of which option you spring for (they’re both worth trying), your goal is to find the threshold of where your pain arises and stay just beneath it. In other words: use as large of a pain-free range of motion as possible, or use as much resistance as you can without creating pain. Note here that discomfort might be acceptable, but pain isn’t.

Pro tip: You may want to try incorporating reverse Nordic curls into your training regimen – this is an outstanding exercise to both lengthen and strengthen the quadriceps tendon when performed appropriately.

Stick with this strategy while slowly scaling up the range or resistance as the weeks go on, making use of pain-free progressive overload for your tendons.

Dealing with tendinosis

The problem with tendinosis is that unhealthy tendons often won’t be painful until a physical demand is placed upon the tissue that challenges it beyond what it is healthy enough to endure. The result can be pain around the knee tendon (just below the knee cap) or around the quad tendon (right above the knee cap) when attempting specific knee-dominant movements.

One of the best exercises you can do for overcoming quadriceps and patellar tendinopathy is to perform Spanish squats (link takes you to a detailed blog article of mine) – they’ve got some solid research behind on them for producing positive changes to tendons around the knee.

Typically if a resistance is too great for a healthy tendon to sustain, the individual simply can’t complete the exercise. But if the resistance is too great for the tendon and the tendon has a generalized case of mild tendinosis, the movement will become painful before the individual can reach their maximal load.

The solution here is not to back off from loading your knee entirely and just hope that things will heal up (they likely won’t) but rather to challenge your knee appropriately so that it receives enough mechanical stimulus to become healthier without being overloaded in the process.

Cause 3: Movement errors and poor joint alignment

Another commonly experienced source of knee pain from pistol squats can result from inadequate joint control around the knee throughout the movement. The ability to volitionally produce and simultaneously control a movement within our body is known as motor control.

Inadequate motor control often leads to various forms of pain and discomfort for muscles, tendons and joints all around the body. We’re often unaware of small imperfections in our movements (in the gym or elsewhere), which can ultimately lead to abnormal stress and forces in our body’s muscles, tendons, and joints.

Even a tiny, unnoticed movement error, when performed repeatedly or against a challenging resistance, can lead to noticeable amounts of pain.

In the case of pistol squats, there are two main factors to be aware of here:

- There is a high mechanical demand (a lot of force) running through the front of the knee (cause 1).

- The knee is supporting a very top-heavy load throughout the movement. A top-heavy load will challenge the knee’s stability in ALL directions (the knee will have to resist all sorts of wobbling).

Regarding this second point, knee wobbling while supporting a heavy load above (i.e., supporting your entire body weight) can stress and strain the knee in various ways if you can’t control your knee positioning throughout the squat.

Here’s why: The knee is inherently known as a hinge joint, which works primarily in one plane of motion, just like a door hinge (bending and straightening).

Now, technically, the knee does have the ability to produce rather minimal amounts of internal and external rotation around the joint (i.e. twisting inwards and outwards); however, this is something that absolutely should be avoided during the pistol squat (otherwise, you’re essentially just grinding away your knee joint under the full weight of your body).

In other words: If the knee works best in a straight-forward plane of motion, but you’re compressing the joint with a heavy load WHILE allowing your knee to collapse inwards (i.e., not squatting with the straight-forward hinging motion that it was designed for), knee structures such as the backside of the knee cap, the patellar tendon (knee tendon) and even the menisci (knee cartilage) can become irritated and painful.

Therefore, maintaining perfect lower limb alignment (via pristine motor control) is absolutely critical for keeping tissues and structures healthy and pain-free during squatting/knee-bending movements – particularly one with a high level of resistance.

Pro tip: Ever notice how much fewer people have pain with double-leg squats than with single-leg squats? Often it’s due to the relative ease of holding both legs in ideal lower body alignment than when compared to trying to do so with a single-leg squatting movement.

Universal solutions for pistol squat knee pain

Regardless of the specific causes of your pistol squat knee pain, there are some highly effective solutions that you can implement. These solutions are designed to improve control of your knee both directly (i.e., practicing your control) and indirectly by strengthening the muscles that help control your knee movement. Let’s start with the latter.

Solution 1: Strengthen your lateral hip rotator muscles

It may seem counterintuitive to work on hip strength for a movement that seems to be predominantly quadriceps (thigh) based, but here’s your anatomy fact of the day:

The muscles that cross the hip joint play a massive role in a person’s ability to control their knee positioning. In particular, the deep external hip rotators have been shown to play an important role in this. These include:

- The glute medius

- The glute minimus

- The obturators

As well, the tensor fasciae latae has a massive effect on knee control, as this is one of its primary functions. Essentially, it acts like a long control arm for the knee since it attaches to the IT band, which then runs all the way down the outside of the thigh, crosses the knee joint and attaches to the upper portion of the tibia (shin bone).

If you want to start this whole process off right, check out my article on the best possible exercise you can do to start rehabbing dysfunctional hip muscles.

Solution 2: Keep your thigh tissue mobile

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is as annoying to deal with as it is common. If you’re unaware of what this condition is, it’s essentially pain arising around the knee joint due to various possible causes. The most common causes are believed to be poor tracking of the kneecap (the patella), overloading the tendons (which I’ve already discussed), and poor mobility of the tissue that crosses the knee joint.

Without doing a hardcore dive into PFPS, the main thing I’d like you to be aware of is that poor tissue mobility of the thigh can contribute to poor knee tracking mechanics (and contribute to knee pain).

You’ll often hear terms like runner’s knee and IT band syndrome being lumped into PFPS, and for the sake of this article, I’m lumping them all under the same umbrella term of PFPS.

So, the solution here is to perform some dedicated soft tissue work to your quads, adductors, and IT band regularly, which will help keep the fascia, muscles, and hopefully their subsequent tendons healthy, mobile, and pain-free.

If your kneecap itself is lacking mobility, it can significantly contribute to symptoms of PFPS. Some simple self-mobilization of the kneecap might help with reducing this issue.

If you have the means to get dedicated massage work from a therapist, go for it! If you don’t, grab a foam roller and start rolling these muscles a few times a week. Or, if you want something more effective (in my personal opinion), grab a barbell and follow along in my YouTube video below:

Pistol Squat regressions and variations

If pistol squats (or any other single-leg squatting variation) are something you’d like to pursue but are being held back by pain or just a lack of necessary leg strength, you don’t have to give up on these movements. Rather, you likely just need to find the right ways to regress and/or modify the exercise until it becomes appropriately challenging without overloading tissues or compromising your technique and form.

Here are some of my favourite variations and regressions for pistol squats. I have used them on myself and many of my clients over the years.

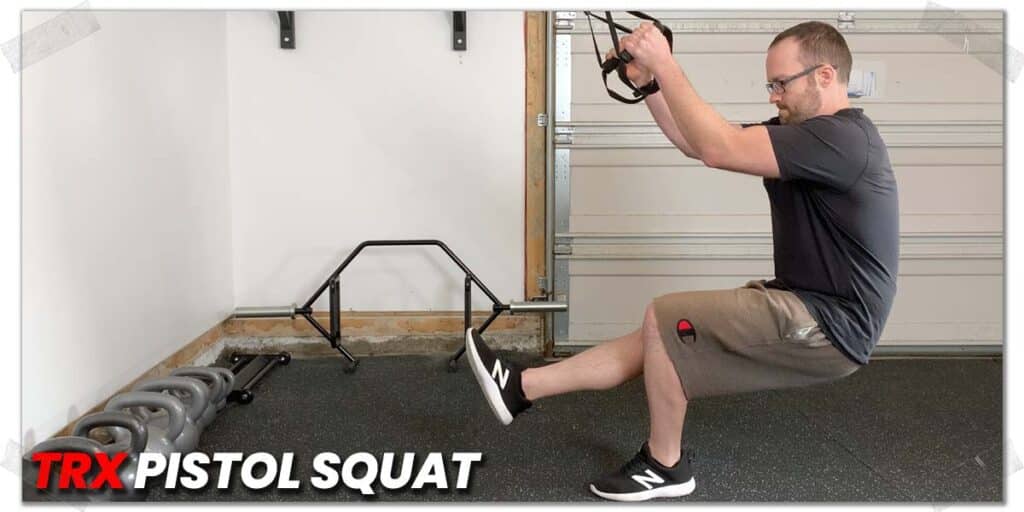

TRX Pistol Squats

The TRX pistol squat is always my go-to when helping others to find a way to control their knee movement while utilizing an optimal load for their knee. Why? Because the TRX allows an individual to do three things exceptionally well:

- Fine-tune the precise load they need.

- Produce full control of their movement with complete concentration.

- Optimize the range of motion most ideal for their needs and abilities.

Here’s how to do it:

- Grab a TRX.

- Sink into your pistol squat in a slow and controlled manner.

- As you lower yourself down, pull on the handles as much as needed to offload the force running through your knee.

- Sink down as far as you can while staying pain-free.

- Once you’ve hit your threshold, return to the standing position by pushing with your foot and pulling with your arms; you’ll quickly determine how much of each you need to do.

Pole Pistol Squats

If you don’t have access to a TRX, or you need a bit more stability and control (the TRX will slightly challenge your stability and control), you can step things down even further and perform your pistol squats while holding onto a pole or rack – such as a squat rack.

From here, you can lean back and sink into your pistol squat. You’ll have maximal control of the movement since you’re holding onto a stationary object while precisely controlling your depth and speed of movement.

The beauty of all of this is you can fully concentrate on controlling your knee positioning while controlling how much load you run through your quadriceps tendon and patellar tendon.

Pro tip: The higher up you grab the pole, the smaller your pistol squat range will be; the lower you grab, the larger your range will be. Don’t be afraid to play around with it to find a height that works best for you!

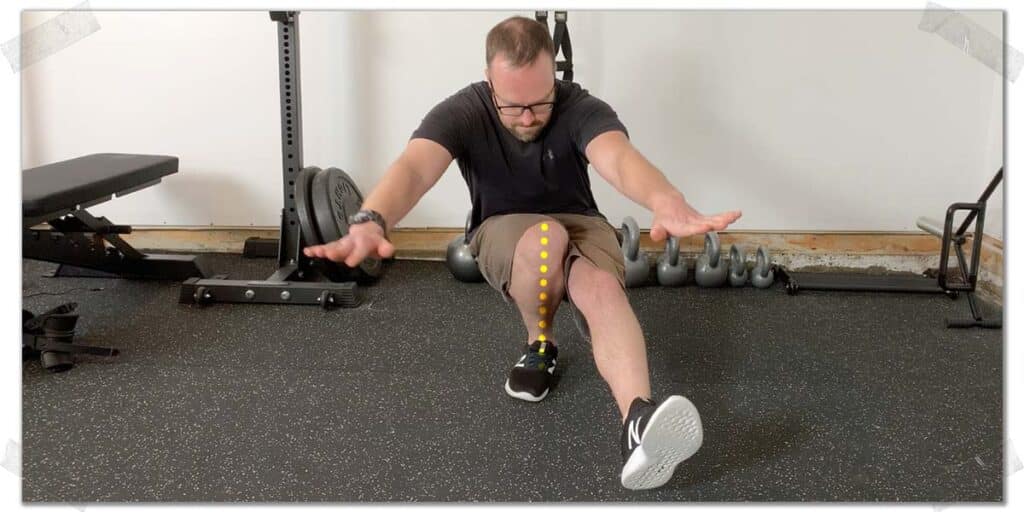

Eccentric-only pistol squats

If you need more of a challenge than what the previous two options offer, or you want to practice maintaining precise control of your knee without holding onto anything (i.e., free-standing), it’s likely worth trying eccentric pistol squats.

Eccentric muscle contraction refers to the controlled lengthening of a muscle. Regarding pistol squats, the eccentric phase occurs when lowering down in the squat.

Concentric muscle contraction occurs when muscles contract (shorten). This occurs when rising out of the bottom of the pistol squat…but we’re not going to perform this phase with this variation.

Performing eccentric pistol squats

To perform eccentric pistol squats, you’ll need a workout bench or chair of some type. The higher it is, the easier it will be. Naturally, the lower it is, the more challenge you’ll face.

All you need to do is slowly perform a pistol squat until you (softly) sit on the bench or chair. From there, stand back up with both legs, then repeat the process over again for as many repetitions as needed.

This is an ideal variation to perform if you’re not quite able to perform the entire pistol squat but are on the verge of being able to do so.

Pro tip: You can hold onto some dumbbells in your hands, or hold a kettlebell at your chest, etc., for some extra resistance or challenge.

Once you can bang out a handful of pain-free repetitions from a standard bench or chair height, try knocking the height down a bit and see if performing some eccentrics to a lower height are still pain-free. If they are, you might just be able to ditch the low bench or chair altogether and get back to performing full pistol squats!

Concluding remarks

Pistol squats are like any other exercise on the face of the earth – they are appropriate for some and not for others, with the appropriateness based on a multitude of individual factors. They’re often painful due to a generalized lack of strength, unhealthy tissues around the knees and/or the individual’s inability to keep the knee and lower extremity in an ideal pattern of alignment throughout the movement.

Don’t ever be afraid to modify and/or regress a movement to fit your needs. This is what all great lifters do. After all, lifting is all about becoming an expert on yourself.

And as you work on becoming an expert on yourself, your muscles, tendons, joints and the rest of your body will repeatedly thank you and afford you many more years of lifting than the average individual.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!