Working out and performing squats is supposed to make you stronger, not break you down and leave you writhing in pain. Even if you only have mild pain or discomfort after squatting, it needs to be addressed. At best, experiencing lower back pain from squatting will interfere with your next one or two workouts, while at worst, it will lead to debilitating, chronic pain that cuts your training career short.

Don’t let that happen to you. And if you read this article, you’ll stand a much better chance of avoiding or eliminating this all-too-common issue.

In this article, you’ll learn the anatomy of lower back pain, the most common causes of lower back pain from squatting, and (perhaps most importantly) how to fix the issue altogether. I’ll also include exceptional resources for optimizing your lower back health.

By the end of this article, you’ll stand a much better chance at being the bulletproof lifter you want to be due to learning the concepts that are proven to keep lifters safe and optimize their lower back health.

So, let’s rock and roll.

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

As I dive into everything here, keep in mind that while I’m presenting lower back issues individually, your squat-induced lower back pain may be the result of more than one particular issue taking place. When I evaluate and treat lifters in the clinic, there are often a few issues causing their pain, some of which are secondary to the main issue at hand.

As an example, it’s rather common to find an irritated nerve root in one’s lumbar spine that’s secondary (arising from) a disc bulge. As a result, I’ll need to use different treatment methods for each issue since these are two different types of tissues. There can be a lot to unpack with low back pain. So keep this in mind as you work through this article and when taking the necessary steps to get to the root cause(s) of your back pain.

Lastly, it should go without saying that your best bet is always to get an evaluation of your back from a qualified healthcare professional, such as an orthopedic physical therapist.

Alright, let’s start talking about the most commonly affected anatomical structures when experiencing lower back pain from squats.

Anatomy basics: Sources of lower back pain

If you’re going to stand any chance of mopping up the pain or discomfort taking place in your lower back (and thereafter keeping it at bay), you need to have a basic understanding of the tissues and structures that can become irritated and thus sore or painful. After all, the only thing better than being a strong lifter is being an educated, pain-free lifter.

So do yourself a favour and read the basics below on lower back anatomy. If you do, you’ll get WAY more out of the topics and concepts addressed later on in the article.

I will keep it short and sweet, I promise.

There are five structures in the back I will briefly run through:

- The intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine

- The facet joints of the lumbar spine

- The nerve roots of the lumbar spine

- The sacroiliac joint

- The superficial & deep muscles of the lumbar spine

Each of these structures can wreak havoc during the squat if not in an ideal state, so let’s discuss why each of these structures matters and how to tell if they’re causing your pain.

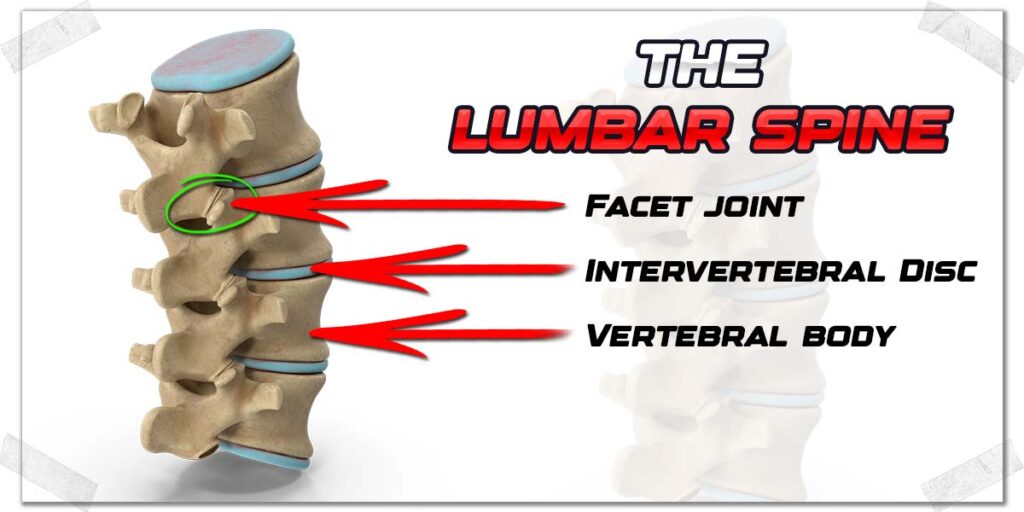

Anatomy tip: The lumbar spine refers to the bottom five vertebrae (bones) in the spine.

Structure 1: The lumbar intervertebral discs

We might as well start by talking about the intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine since they’re notorious for causing pain in the back.

Intervertebral discs (often just called discs) are the hockey puck-like pieces of fibrocartilage that sit between the vertebrae (spine bones) in our back. There are five of these discs in the lumbar spine.

These discs help to provide cushioning between each vertebra along with smooth, yet strong, movement within the spine. Unfortunately, these discs are prone to becoming deformed, tearing, and otherwise dysfunctional, which can lead to varying levels of back pain and dysfunction.

Common discs issues in the lower back can include:

- Disc bulges

- Disc herniations

- Disc extrusions

- Disc sequestration

- Annular tears (tearing of the fibrocartilage rings of the disc)

Pro tip: You may often hear people say they’ve “slipped” a disc in their back, which is a misnomer, as discs do not slip out of place. The term is often used to refer to a disc bulge or herniation that has taken place, whereby a portion of the disc has deformed in its shape—but has by no means “slipped”.

Disc issues (of various extents) are common in the average population, as well as within the lifting community (the reasons for this will be discussed later on in this article), however, a disc bulge doesn’t always correlate with pain.1

Indications you’re dealing with an irritated disc

There are a few telltale signs that suggest your lower back pain is arising—at least, in part—from one of your lumbar discs. These telltale signs are:

- Lower back pain that worsens or intensifies with prolonged sitting

- Lower back pain that worsens with forward bending (flexion of the lumbar spine) either after a single movement or repeated forward bending movements

Of course, neither of these signs guarantees that the issue is from a disc (lower back pain doesn’t deal in absolutes). However, the science makes for a high clinical prediction that a disc is involved if an individual’s back pain worsens with both of these activities.

Thankfully, discs can be quite resilient and bounce back from unhealthy states if given the right strategies and exercises, which, of course, I’ll be discussing later in the article.

“If you’re going to stand any chance of mopping up the pain or discomfort taking place in your lower back, you need to have a basic understanding of the tissues and structures that can become irritated and thus sore or painful.”

Structure 2: The lumbar zygapophyseal joints (facet joints)

The human spine is able to bend and move as a result of multiple vertebrae (spine bones) that link together. This “linking” occurs via the specialized joints where one spine bone articulates (moves) with the other.

These joints are known as facet joints. Anatomically, they’re known as zygapophyseal joints or Z-joints (but pretty much everyone calls them the facet joints).

Like any other joint in the body, these little joints (about the size of your thumbnail) are lined with cartilage, allowing each joint surface to glide smoothly on the other, just like rubbing two ice cubes together.

These joints are prone to becoming irritated (for numerous reasons), at which point they become painful. I’ll discuss the details later in this article.

Indications you’re dealing with an irritated facet joint

When irritated, Facet joints tend to produce pain sensations that are sharper and more focal in nature—and these sensations can often be rather intense. Unlike myalgic pain (pain arising from muscles), which is typically more diffuse and achy in its nature, facet-joint pain is often easy to localize (patients can typically place their finger right over the spot where they feel their pain).

Often, the pain from an irritated or unhealthy facet joint in the lumbar spine won’t be too noticeable when remaining still; the pain is more often felt as the joint is forced to move (you bend forward, sideways, twist your spine, etc.).

You’ll often notice that pressing directly on top of the joint (about an inch to the side of the spiny bone running right down the middle of your back) reproduces the intense pain. The more irritated this joint is, the less firmly you’ll have to press your finger over it to feel any pain.

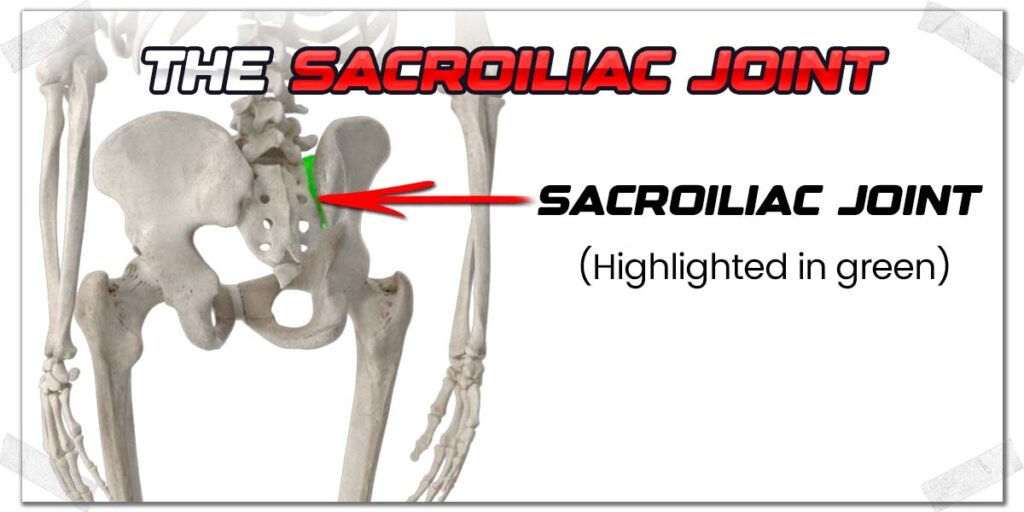

Structure 3: The sacroiliac joint (SI joint)

The Sacroiliac joint (most always called the SI joint) is the joint that forms between the sacrum and the ilium (the ilium is what most people refer to as the hip bone). There is one SI joint on each side of your body.

This joint is a large and irregularly shaped joint, and while it doesn’t have a lot of natural movement that it produces, it still has a reputation for becoming irritated and painful.

This pain can arise for different reasons. For most lifters who are otherwise healthy, the joint essentially becomes a bit “jammed up” in a manner that prevents it from producing its ideal articulation when moving (walking, rolling over in bed, squatting, etc.).

Indications you’re dealing with an SI joint issue

Thankfully, the SI joint has a set of clinical prediction rules that have been shown to reliably indicate if the pain one feels in their lower back is arising from this joint. If you have two or more of these conditions that cause your pain (i.e., the back pain that is bothering you), there’s a high likelihood that your SI joint is involved.2–4 It’s essentially a slam dunk for confirming SI joint dysfunction if you have three or more.

Here are the clinical prediction rules for SI joint pain:

- A positive Fortin’s finger test

- Pain that occurs when rolling over in bed

- Pain that occurs when moving from a sitting to a standing position

- Pain that occurs when walking

While having a jammed or irritated SI joint isn’t pleasant, thankfully, it’s a very easy issue to mop up. The quickest way is with an adjustment from a qualified professional, such as a qualified physiotherapist or chiropractor.

If getting professional treatment isn’t in the cards for you, you can try some self-mobilization techniques. Check out the video below for more information!

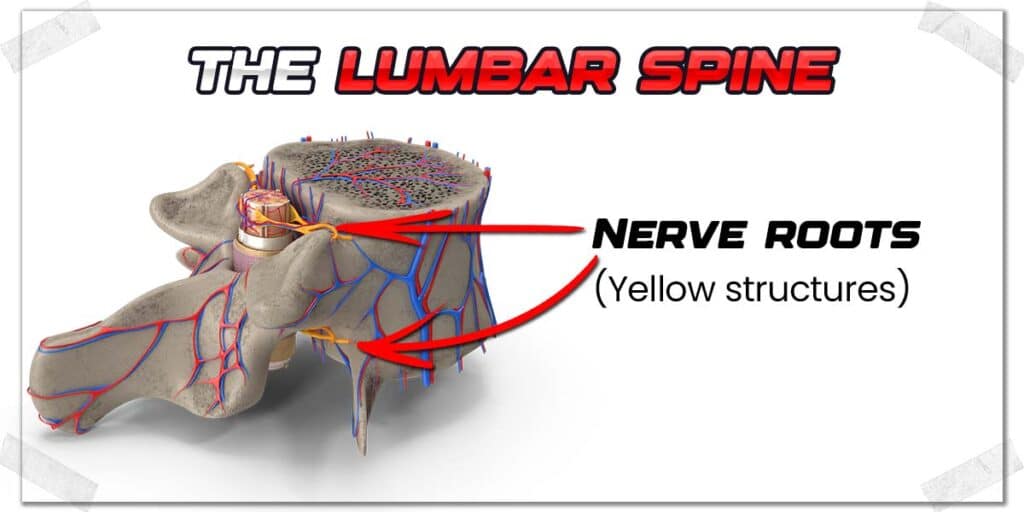

[YOUTUBE VIDEO]Structure 4: The lumbar nerve roots

Your leg muscles are able to contract and relax due to the nerves that communicate with them. These nerves run from your brain to your spinal cord, then branch out, pass through a small opening between your vertebrae (known as the intervertebral foramen) and run down throughout your legs.

These nerve roots can, at times, become irritated, leading to pain that’s perceived within the lower back or even pain that travels into your butt or back of your leg.

In younger lifters (those under forty years of age), this nerve irritation is often the result of lumbar disc deformity, whereby one of the lumbar discs presses upon the nerve root (such as when the disc bludges).5 However, it can also arise for other reasons, which won’t be covered in this article.

In Master’s category lifters (age 40 and above), there’s also the issue of nerves becoming irritated as a result of stenosis, where the intervertebral foramen abnormally narrows (typically due to degenerative changes). Stenosis won’t be covered in this article.

Indications you’re dealing with an irritated nerve root

Nerve pain is not a fun thing to experience. When a nerve root in your lower back is lit up, it will often produce intense pain that feels sharp, intense, and electrical-like in nature, as if you’re getting zapped by an electrical current.

Additionally, irritated nerves do not like being stretched, so bending and moving in ways that lengthen or stretch the nerve will likely not be tolerated all that well.

When a nerve root is pinched or irritated by a structure near the spine (such as a bulged disc or from stenosis of the spine), it can produce a very specific type of pain known as radiculopathy or radicular pain.

This condition involves pain travelling along the path of the nerve that has been affected at the nerve root level, with the pain being perceived anywhere along the extremity (in this case, down the leg).

Sciatica is a condition that can arise when one or more nerve roots are affected. The pain can indeed be felt in the back but is often also felt along the back of the leg and can be felt all the way down to the heel or bottom of the foot in more severe cases.

Structure 5: The deep & superficial back muscles

Pain or discomfort that arises within the lower back due to abnormal muscle tension (tightness) is known as myalgic pain. There are numerous muscles that run along the length of the lumbar spine.

Some of the key muscles of the lower back that can often become painful in lifters, athletes, and active populations, include:

- The erector spinae muscles (three superficial muscles on each side of the back)

- The multifidi muscles (one on each side running directly up the spine)

- The quadratus lumborum (a muscle attaching along the side of the lumbar spine)

- The psoas (hip flexor) muscle, which attaches to each of the lumbar spine

These muscles, be they the deeper ones (such as the mulfidi muscles) or the more superficial muscles, such as the erector spinae muscles, are prone to becoming stiff, tight, achy, and sore for numerous reasons.

In the absence of trauma (a sudden, forceful event that causes direct tearing of the muscles), these muscles typically become painful from being overworked.

Pro tip: A tight hip flexor muscle can cause lower back pain since the psoas (main hip flexor muscle) attaches to each of the five lumbar vertebrae, wreaking havoc on low back mobility and function if the muscle is tight or otherwise unhealthy.

Muscles in and around the lower back can become overworked for different reasons. Sometimes, this is simply due to excessive training volume (lots of heavy squats, numerous back exercises being performed, etc.). Other times, the muscle(s) become overworked as a result of dysfunction arising elsewhere in the torso.

When it comes to dysfunction, it’s not uncommon for a given muscle to work excessively hard if another associated muscle isn’t strong or healthy enough to perform its regular duties.

A classic example of this is weak or unhealthy deep stabilizer muscles within the hip (such as the glute medius and glute minimus muscles) not contributing to creating ideal pelvic stability during the squat. As such, the quadratus lumborum or the erector spinae muscles, in a sense, have to pull double duty to try and make up for this lack of hip stabilization occurring.

The result of these dysfunctional patterns (which are surprisingly common) is other muscles doing more work than they should, which leads to notably tight, sore, and, ultimately, unhealthy back muscles.

Indications you’re dealing with muscular issues in your back

This type of pain tends to be perceived as:

- Tightness

- Aching

- Dull

- Diffuse (spread over a large area)

You may find that heating your lower back (using a heating pad or device of some kind) feels rather nice and helps decrease stiffness when moving thereafter. This is often an indication that there is excessive muscle tension present.

Pro tip: Many times, the muscles of the lower back are often tight, painful, and in spasm as a secondary reaction to pain and dysfunction arising elsewhere in the lower back, such as the facet joints or an irritated nerve.

Alright, that’s it for basic lower back anatomy and pathoanatomics (why pain can occur within these structures). Time to now look at what can go wrong with squats and how it leads to dysfunction in the back (and what to do about it).

Squat induced: Why the back can hurt from squatting

Now that you’ve read through the brief (but critical) rundown on basic tissues and structures of the lower back that can cause pain, we next need to address why these issues can arise during or after squatting.

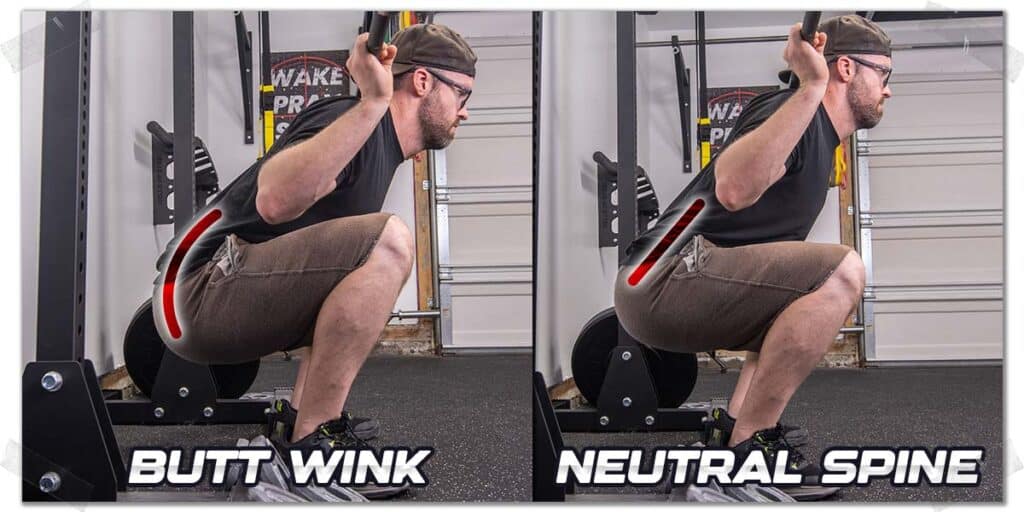

Lumbopelvic flexion (butt wink) during the squat

Lumbopelvic (lumbo = lumbar spine, pelvic = hips) flexion (forward bending) refers to the rounding of the lower back, which takes place in numerous lifters who squat beyond what their hip mobility can adequately produce. It doesn’t matter if it’s a barbell squat, front squat, goblet squat, etc.; lumbopelvic flexion can occur with any type of double-leg squat.

This is one of the most common issues that affects low back health in active populations who perform squats.

Within the fitness and lifting community, you’ll often hear this low-back rounding phenomenon termed “butt wink.” It is something that should be avoided when lifting with weight across your back (barbell squats) or any type of loaded squat (front squat, goblet squat, Zurcher squat, etc.).

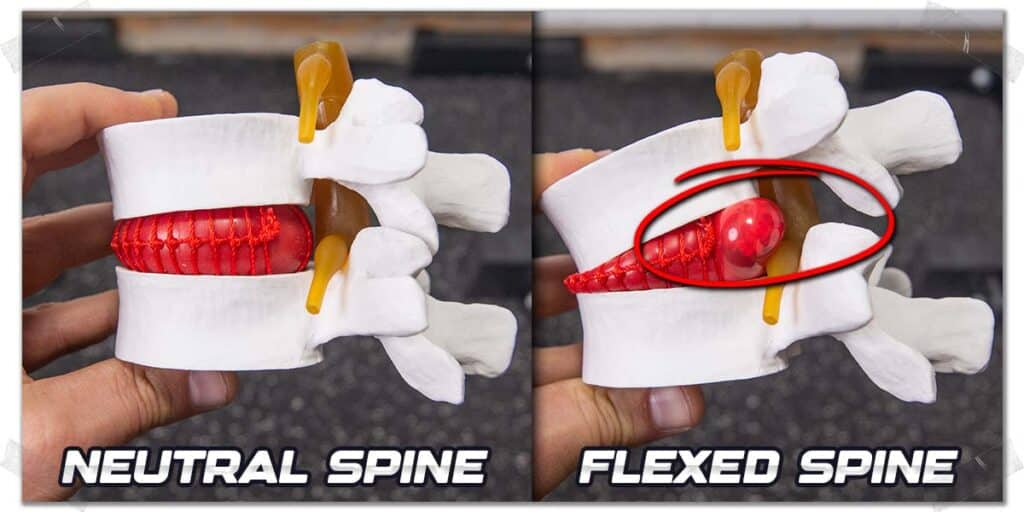

Here’s why: The rounding of the lower spine at the bottom of a squat can lead to various forms of lumbar disc derangement since this spine-flexion movement places immense pressure on the posterior (back side) of the disc, particularly when you have a loaded barbell strapped across your upper back.6

The solution here is to avoid any rounding of your lumbar spine during the squat like the plague. This is especially true if you already have disc issues in your spine (repeated butt-winking will only serve to make the issue worse—not better).

If you want to read all the geeky scientific details, check out this scientific article: Dynamic Deep Squat: Lower-Body Kinematics and Considerations Regarding Squat Technique, Load Position & Heel Height

If you’re a competitive lifter and need to hit your target depth (i.e., the crease of your hips below the height of your knees), you’ll need to attack your hip mobility like mad to ensure you can safely hit this depth while keeping your lumbar spine in a relatively neutral position.

To learn how to do more of this, read my section later in this article on improving sensorimotor awareness within the spine.

Tissue overload & lack of recovery interventions

Sometimes, it’s not a matter of your technique being off but rather training more than your body can keep up with. It’s important to train hard but to recover even harder.

I always use the analogy of a race car; the more aggressively the car is driven and pushed to its limits, the more maintenance and work it routinely needs in the shop to keep every component working in an ideal fashion. This attention to maintenance leads to improved performance and lifespan of the car, and it’s the exact same with your body’s performance and lifting lifespan.

Related article: Injuries & Reclaiming Exercise Motivation (Practical Steps)

If all you’re doing is lifting without giving your body the time it needs to physiologically recover from your squats (and other lifts), you might be staring down the barrel of back pain.

While an entirely separate article could be written on this topic, here’s what I would suggest as a starting point to ensure you’re giving your body the respect it deserves while pushing and challenging yourself in the gym:

- Learn to appropriately manipulate your training loads and volume through periodization. This is what every successful lifter and athlete does. If you’re not sure how to go about doing this, consider working with a strength coach or reading the book Periodization by Tudor Bompa (please note: this is an affiliate link that takes you to Amazon. Any purchases you make through this link will provide me with a very small commission at no extra cost to you, which I use to offset the cost of running this website!).

- Take your recovery seriously. When it comes to your back, make sure you’re setting aside time each week for therapeutic movement, self-soft-tissue treatment, and other forms of active and passive recovery that keep your bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and nerves in a happy state.

I get that it’s more fun to lift weights than to perform recovery interventions. However, it’s hard to lift weights when your body is in pain from repeatedly hard bouts of training without receiving any subsequent recovery benefits.

“When it comes to dysfunction, it’s not uncommon for a given muscle to work excessively hard if another associated muscle isn’t strong or healthy enough to perform its regular duties.”

Take care of your body and your body will take care of you, ya know?

Cleaning it up: Interventions for lower back pain from squats

Now that you’ve got the rundown on the structures involved with lower back pain from squatting and why these painful conditions can arise, it’s time to get down to business and talk about the steps to take to reduce your lower back pain and get you back to pain-free squatting.

As always, remember that your best bet is likely a holistic approach and one that combines multiple therapeutic exercises and strategies. For most lifters whom I treat in the clinic for lower back pain, I often give them multiple therapeutic exercises and strategies to implement.

McKenzie Extensions: Dealing with lumbar disc pain

For those dealing with pain in their lower back as the result of an irritated or bulged disc, I often advocate for performing McKenzie Extensions. This therapeutic movement comes from a treatment system known as the McKenzie Method or Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy (MDT)

It’s a system that has good scientific evidence behind its effectiveness, and the simplicity involved for patients performing exercises to improve their disc health in their lumbar spine makes it an ideal home exercise for many lifters dealing with disc derangement issues in their lower back.

The theory behind this technique involves extending the spine (bending it backwards), which helps to push the deranged disc back towards its center, thereby reducing the primary and secondary pain that can arise when the disc is deformed (budged, herniated, etc.).

The underlying premise of this treatment technique is to move the body (in this case, the lower back) in a direction that it responds to in a favourable manner.

A favorable response involves the lessening of symptoms and the presence of any pain or symptoms arising within the extremities (in this case, the legs) to progressively move further up the leg(s) (towards the lower back) and thereby dissipate further down the leg(s.)

This decrease in pain further away from the back (i.e., down the leg) is known as centralization and is a sign that the issue within the lower back is improving.

To read some of the specifics and scientific findings on the McKenzie Method, you can check out these scientific articles:

Performing McKenzie extensions

The execution of the McKenzie extension will vary from one individual to the next, as the treatment is designed to be individualized to the tolerances and needs of each individual.

Nonetheless, here’s the basic rundown of how to perform the standard McKenzie extension:

- Lay on your stomach and rest here for a moment, taking time to note how your lower back feels.

- While keeping your hips on the floor, slowly press your upper body off the ground. This will produce a backward bending (extension) of your lumbar spine. Press up as far as tolerable—don’t push through any nasty pain.

- Hold this position for a few seconds, then slowly lower your upper body back to the floor. Take a second or two to evaluate how this made your lower back feel, then repeat the movement.

- Perform ten to twenty repetitions, taking note of how your lower back feels after each repetition.

If your lower back doesn’t worsen—or ideally, feels better—this is a sign that your lower back tolerates the movement. If your pain centralizes, it’s a good sign that you’re making your back happy with this movement.

It may be worth getting in the habit of performing this therapeutic movement multiple times per day.

You can also try performing this press-up movement before the start of your workouts, regardless of whether you’re about to perform an upper or lower-body training session.

Nerve glides: Improving your neurodynamics

Many lifters who experience back pain from disc-related issues also have nerve irritation (secondary to the deformed disc pressing on a nerve root). Irritated nerves are a unique beast in that they respond to (i.e., calm down) specific movements (known as flossing or gliding) when performed correctly.

The ability of a nerve to undergo adequate movement without becoming overly stretched refers to the nerve’s dynamic abilities or neurodynamics.

Irritated nerves—just like irritated muscles—lose their ability to tolerate stretching and lengthening movements. Unlike muscles, however, they do not tolerate prolonged stretches (i.e., a static stretch that places the nerve in a continual state of tension).

As such, it’s imperative to find ways to calm the nerve through flossing and gliding exercises that take the nerve through waves of high-to-low tension. When performed properly, these undulating patterns of tension can be immensely therapeutic for nerves.

To learn more, check out the video below by the Physio Tutors!

Sensorimotor retraining: Utilizing perfect range of motion

If you suffer from “butt wink” but have a hard time knowing or feeling the point in your squat when your lower back begins to round, it will be hard for you to know how deep you should squat. (Remember, squatting deep enough to produce butt wink is not ideal, especially if you already have low back pain.)

Having the ability to feel and know the point at which your lower back begins to move and subsequently resist this unwanted movement is known as sensorimotor awareness.

Often, lifters can’t feel or perceive the point in their squat where their lumbar spine begins to move out of its ideal neutral position. If you’re one of these lifters (it’s common, so don’t worry), there are two simple strategies you can practice that can help improve your awareness of feeling and interpreting movement taking place within your body.

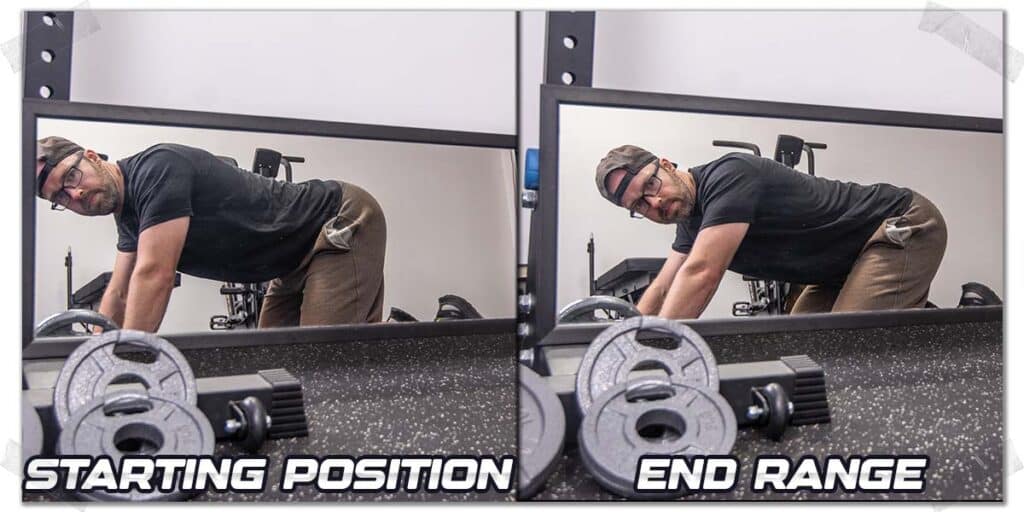

The mirror drill

When lacking sensorimotor awareness, using visual feedback is one of the first strategies I often implement for overcoming this type of deficit. By providing real-time visual feedback of your body during a movement, your brain can better figure out what exactly is transpiring regarding how you’re coordinating and moving your body.

Visual feedback is immensely helpful for allowing our brain to decipher and correct any unwanted movement that is occurring when volitionally performing movements or exercises.

The mirror drill is as simple as it sounds:

- Stand in front of a mirror and turn yourself sideways so that you can see your lower back’s position when squatting.

- Slowly squat down until you see your lower back begin to round.

- Return to the upright position and repeat the squat, this time stopping your squat just before you begin to see movement in your lower spine.

As you gain awareness of what this unwanted movement in your lower back feels like, begin performing a few reps while looking straight ahead (so that you’re not looking at the mirror). Check your position in the mirror once you believe you’ve squatted as low as possible without rounding your lower back. If it has rounded, you’ve got more practice ahead of you.

Related article: Back Pain From Box Squats | Causes | Fixes | Expert Tips (Full Guide)

If it’s still flat, try slowly dropping into your squat a bit more; if your back begins to round the moment you initiate more downward movement, you stopped at the right depth! If you can still drop lower before any movement occurs, you’ll need to keep practicing until you’re able to consistently stop your squat (without looking) just before the point at which flexion occurs.

Using tape on your lower back

Using a strip of athletic tape, kinesiology tape, or any similar tape while holding your lower back in a neutral position (the same position in which you squat), place a strip approximately six inches long down the center of your lower back (covering the spiny bits that you can feel with your fingers). The tape should run down to the top of your butt crack.

Make sure the tape is securely adhered to your skin.

Now, slowly squat down to the point where you feel the tape beginning to pull on your skin. This is the depth in your squat at which your lower back begins to round.

By placing some tape on your lower back, the nerve endings in your skin will allow your brain to feel when movement is occurring in your lower back. As the tape pulls your skin, your skin’s nerve receptors activate and send this information regarding your lower back’s positioning to your brain.

Pretty cool, eh?

The goal is to confidently know the maximal depth you can achieve in your squat immediately before the tape begins pulling on your skin (signifying movement in your lumbar spine).

Once you can accurately stop each repetition just before the tape pulls your skin, try performing your squats without the tape. Record a video of your squats and then watch it to see if you’re stopping just before your lower back begins to round at the bottom of your squat.

This is an outstanding drill I use with lifters and patients alike when their lower back pain is caused by poor sensorimotor awareness. Once you improve any sensorimotor deficits within your lower back, you can avoid unwanted “butt wink” taking place during your squats.

RELATED CONTENT:

Switching to other exercises

Naturally, it may not be worth trying to perform the barbell squat (or any other type of double-leg squat) as you work through your lower back recovery. Don’t sweat it, though; there are other outstanding lower-body strength training exercises that can continue to strengthen your legs sans back pain.

If it were me dealing with lower back pain when trying to squat (been there before, believe me), this would be a list of the exercises I would substitute for the squat until I rehabbed my lower back to a pain-free state:

The Bulgarian split squat

The Bulgarian split squat would be my first barbell squat substitute, if possible. This exercise, in all honesty, would be the leg exercise I would select if I were only permitted to do one leg exercise for the rest of my life.

It will hammer the glutes and quads, just like traditional squats, but will also target the deep hip stabilizers on the stance leg while simultaneously lengthening and mobilizing the psoas and rectus femoris muscles on the trailing leg.

Additionally, you won’t need to load up heavy weight on your spine for this exercise; just a few lighter dumbbells in hand will likely do the trick. And since it’s hard to round your lower back when doing this exercise, you’ll likely find that it’s easy to keep your lumbar spine in a neutral position throughout the exercise.

In fact, if you haven’t been performing this leg exercise as part of your training, you may want to make it a staple of your training pursuits as time goes on—it’s that effective.

Sumo deadlifts

Sumo deadlifts are another absolutely outstanding exercise to try if you’re dealing with lower back pain from the squat. Unlike conventional deadlifts, this variation won’t place your lower spine into any notable flexion; the wider stance forces more movement to occur through the hips while the lower back stays in a more upright position.

What makes the sumo deadlift so ideal is that it targets every muscle in your lower body. Your glutes, hamstrings, adductors, and quadriceps will be forced to contribute to the exercise, making it a back-friendly and time-efficient lower-body exercise.

Slow leg extensions

Leg extensions are a fail-proof exercise to perform if your lower back simply can’t tolerate any standing or loaded exercises. While leg extensions won’t target your glutes, adductors, or hamstrings, they’ll certainly take care of (i.e. strengthen) your quadriceps.

During my days of rehabbing my lower back, I would perform slow leg extensions with moderate resistance, as the increased time under tension on my quadriceps felt amazing, and I wouldn’t have to worry about irritating my knees from repeated heavy knee extensions.

Belting up: Should you wear a weightlifting belt when squatting?

I often have lifters, athletes, and patients ask me if wearing a weightlifting belt when squatting will help reduce, eliminate, or prevent their low back pain from occurring.

There is a lot to unpack with this topic, and it’s worth knowing that there are valid points to be made on both sides of this age-old debate.

Without going into the hardcore details and while remaining as objective as possible, here’s what you should know when it comes to wearing a lifting belt when squatting:

- Studies regarding weightlifting belts have found them to be helpful and detrimental in certain aspects – it can be a mixed bag depending on which study you look at.

- One study found that when worn properly and with proper breathing technique, a tight-fitting belt reduced spinal loading by 10% in lifters.7

- Research as also found that there is a statistically higher injury rate or reports of lower back pain in lifters and athletes who wear belts than those who don’t.8

At the end of the day, whether you choose to wear a lifting belt or not is up to you. Just know that while wearing a lifting belt for squats can be helpful, it won’t shield you from back pain if you already have notable back pain to begin with or have poor squat technique.

If you want to read up more on this topic, my buddy Avi has a great article covering this topic over on his site powerliftingtechnique.com.

Additional help: Lower back pain resources

There’s a lot to sort out when it comes to getting rid of your lower back pain. As I’m sure you’re aware, I can’t do it all within a single blog article. But now that you know the basics, including the first steps to take, the next thing I can do is provide you with fantastic, trustworthy, and scientifically proven resources that can help you continue to learn about how to solve this issue.

Here are some key resources I often recommend to fellow lifters and patients who are dealing with lower back pain, be it from playing sports, lifting weights, or just trying to get on with their daily lives. I hope they’re helpful! (Please note: these links will take you to Amazon, and any purchases you make through these links will provide me a very small commission at no extra cost to you, which I use to offset the cost of running this website!)

The Back Mechanic By Stuart McGill

Gift of Injury By Brian Carroll & Stuart McGill

McKenzie Method: Treat Your Own Back By Robin McKenzie

Final thoughts

Lower back pain and injuries can be incredibly frustrating to deal with. Thankfully, they’re rarely lifting-career-ending. You’ll need to be smart with your path forward, but this is a doable process. Find a healthcare professional you trust, learn about your condition, and respect your body as you move forward. You’ll get through this, and you’ll come back stronger.

References:

Frequently Asked Questions

Since low back pain when exercising is so prevalent, I’ve included a few brief answers to some frequently asked questions that frequently make the rounds in gyms, lifting communities, and the internet.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!