Building a bulletproof set of hamstrings should be a high-priority goal for anyone who loves to strength train or who wants to avoid pain and injuries that often arise from a weak backside. But building some robust, injury-deterring hamstrings at the expense of incurring knee pain is a bit ironic (to say the least). This article has been written to help you achieve the former without incurring the latter.

Knee pain from leg curls often arises due to excessive hyperextension of the knee, abnormal muscle tension, the presence of a Baker’s cyst, meniscal or articular issues of the joint, and poor movement control. Solutions involve improving technique, reducing muscle tension, and modifying the curl.

Now, there’s a whole lot to unpack here, so if you want to know the details on how to build bulletproof hamstrings without knee pain, keep on reading!

Related article: Spanish Squats for Patellar Tendinopathy: How | Why | When (Must Know)

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including for pain behind your knee with hamstring curls. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

Want to be able to perform leg curls by hooking up a dumbbell to your feet? Check out my review above if you’ve never heard of the MonkeyFeet! You can use the discount code “strengthresurgence” on the Animalhouse Fitness website for 10% off any of their products!

As we kick off this article, keep in mind that I’m assuming your knee pain is confined somewhere within the proximity of the joint itself, on the side of the knee or behind the knee. While knee pain with the leg curl can manifest as pain on the front side of the knee, it’s much less common than in the regions mentioned above, so I won’t be discussing anterior (front-sided) knee pain within this article.

Issue 1: Technique errors

The easiest place to start with fixing/eliminating your knee pain is to ensure that your leg curl technique and execution are on-point. If your knee pain is being driven by technique errors, one can often significantly reduce (if not eliminate) the pain nearly immediately by cleaning up any flaws in the movement.

If your pain is still present after optimizing your movement, you can at least rest peacefully knowing that you have optimal technique and are thus much less likely to run into issues further on down the road as a result of your flawless technique.

Technique error 1: Hyperextension of the knee

An all too common leg curl mistake that individuals make is hyperextending (excessively straightening) their knee in between each repetition. Not only can this rob you of strength and size gains with your muscles (for super geeky reasons FAR beyond the scope of this article), but it puts unnecessary stress and strain on the knee joint and surrounding structures.

Regardless of which type of leg curl you’re doing (standing curl, prone curl, seated curl, etc.), you don’t want to straighten your knee to its absolute fullest extent between each repetition (even if it doesn’t cause any pain).

If you’re using a machine for your curls and you haven’t set it up for optimal positioning, the machine can force your knees into hyperextension between each rep. So, start by making sure that any machine you’re using is set up so that it won’t force your knees into an uncomfortably straight position.

Then, even with the machine set up ideally, I personally advocate for aiming for straightening your knee to around 90 – 95% straight (i.e., almost straight but not quite). Not only will this offload any potential stress to your knee joint (by keeping the force running through your hamstrings), but it will keep your hamstrings from getting a little rest break between each repetition, which can make your exercise much more challenging (thus, effective) for the muscles themselves.

There can be arguments made against this approach. Still, for beginners and those who are prone to experiencing knee pain with leg curls, I advocate for only straightening the leg to 95% of its range. Doing so helps ensure you reduce the risk of unnecessary stress on the knee.

Technique error 2: Excessive resistance

Just as with the previous error, excessive resistance (i.e., beyond what your body can reasonably tolerate) should be avoided for any type of leg curl exercise (prone, seated, standing, etc.). Challenging your hamstring strength with excessive weight is not the same as doing so with optimal weight.

- Optimal weight refers to the minimal amount of weight required to elicit the stimulus you’re after.

- Excessive weight or resistance refers to using more weight than what is required for your hamstring muscles.

Related article: Knee Pain from Leg Extensions: Why it Happens & How to Fix it

Like any other muscle(s) in your body, your hamstrings are prone to becoming irritated, unhealthy and painful if exposed to excessively heavy weight or resistance. This can happen within a single exercise session or as the result of multiple, repeated sessions that expose the hamstrings to loads heavier than they can effectively tolerate.

Remember: Train to stimulate, not annihilate.

Technique error 3: Poor movement control

A third technique error that commonly gets individuals in trouble with knee pain when performing leg curls comes from poor movement control.

Typically, this is seen in the form of using excessively fast speed in either the concentric phase (the phase of movement in which the knee bends/leg curls) or during the eccentric phase (the phase where the leg straightens). I’ve even seen it occur in both phases simultaneously.

Excessively fast movement during any portion of the leg curl can put increased stress and strain on the muscles, tendons, or other knee structures.

Unless you’re an advanced lifter or are explicitly training for explosive power, you’re best off to keep your leg curls slow and controlled at all times. This will not only reduce unnecessary stress and strain on the knees and associated tissues, but the slow movement will also hammer your hamstrings harder due to the increase in time under tension with each repetition.

Pro tip: Slow repetitions increase what’s known as time under tension for the muscle(s) you’re exercising. This leads to more significant amounts of mechanical stress on the working muscle(s), which can produce muscle hypertrophy (size increase) and increases in muscle strength.1,2

Issue 2: Muscular issues

If your leg curl technique is on point and you’re still having discomfort, the next source you might want to consider is any of the muscles involved with the hamstring curl or within the proximity of the knee itself.

The following muscles below can be commonly involved with knee discomfort for various leg curl exercises. Keep in mind that it’s not an exclusive list. Still, these muscles should be the starting point to consider when working on getting to the root cause of your discomfort or pain.

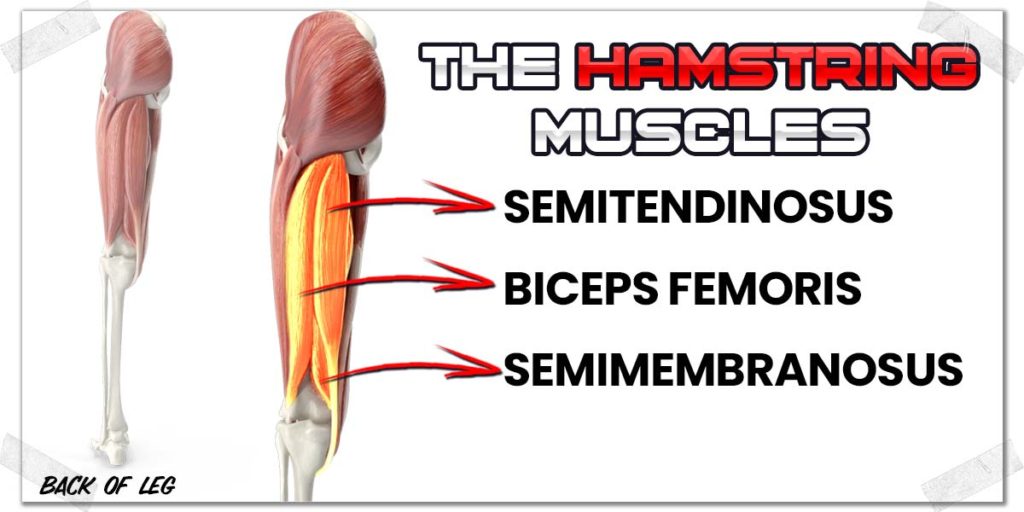

The hamstrings

As you might be aware, the hamstrings are a group of three separate muscles that cross your knee joint. They are the muscles that allow us to flex (bend) our knees when they contract.

If any of the three muscles are tight, you may feel discomfort anywhere along the back of your thigh or even around your knee. If any of the hamstring tendons (which attach just below the knee joint) are unhealthy, such as with the condition of tendinopathy (think tendonitis, but slightly different), you might also feel discomfort as a result.

Related article: One Hamstring Tighter Than the Other? Here’s Your Solution

You’ll want to do your best (or, more ideally, get insight from a qualified professional) for why your hamstrings are tight or unhealthy. Based on the underlying cause, treatment techniques designed to reduce muscle tension and restore mobility might be of help.

These techniques can include:

- Compression flossing

- Dynamic stretches and mobility routines

- Foam rolling techniques

If one or more of the hamstring muscles are strained, you’ll likely need to back off the hamstring exercises for a little while until the muscle is less sensitive to leg curls and other exercises.

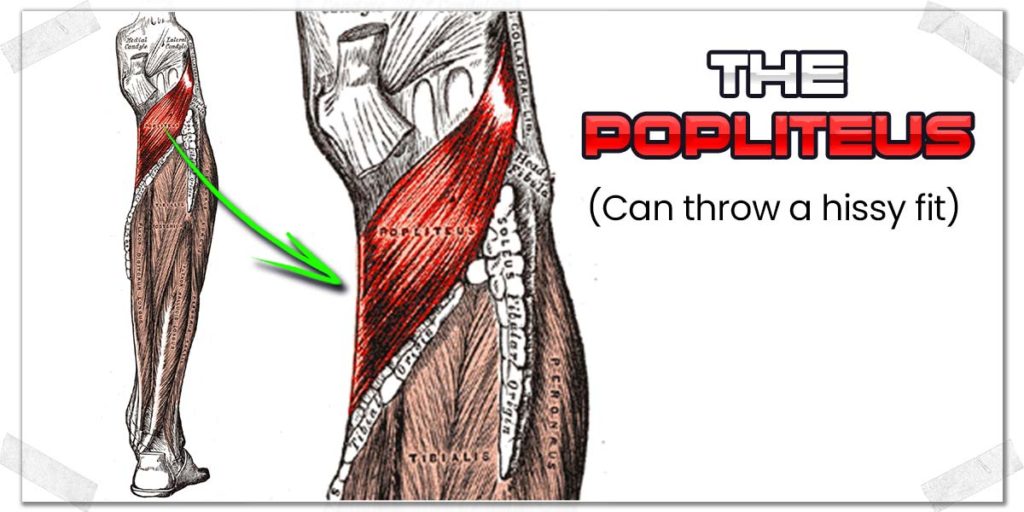

The popliteus

This sneaky little muscle is notorious for causing discomfort on the back of the knee.

The popliteus works primarily to unlock the knee. As a result, when this muscle is abnormally tight, it may become uncomfortable or even painful to produce full extension of your knee (known as terminal knee extension).

If you only experience your knee pain when your leg is entirely straight, you’ll definitely want to ensure you’re not committing technique error 1 of this article, and then try to get your abnormal popliteal tension under control.

The popliteus is a bit of a tricky muscle when it comes to self-treatment. Still, if you’re keen on treating it yourself, you can provide some sustained pressure to it with your thumbs to help drop its resting tone a bit. If you want the full details, you can find them in my article dealing with pain in the back of the knee while squatting. Scroll down to the section dealing with the popliteus, where you will find the details!

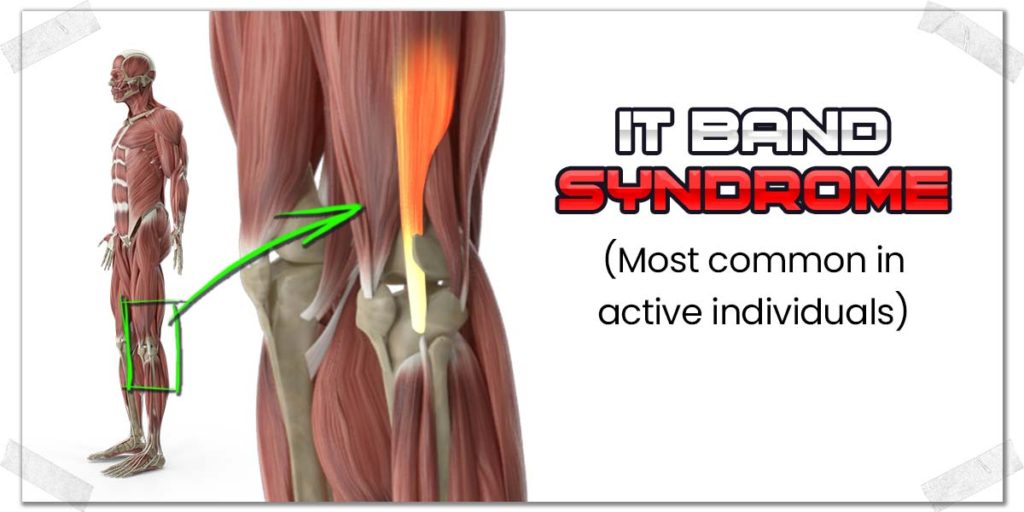

IT band friction

If you’ve been noticing that your pain has been located more along the outside of your knee, and it feels more so like an aching feeling than a sharp, stabbing feeling, it could be an excessive amount of friction being generated on the lower part of your IT band (the iliotibial band).

It’s not an uncommon condition, and it tends to be much more prevalent in active individuals. I’ve written a detailed article over on PowerliftingTechnique.com on how to overcome this issue. The article is geared for those dealing with pain during squatting, but the concepts largely apply to pain with leg curls as well.

The main takeaway is that you’ll likely experience optimal recovery from this condition by improving tissue mobility of your IT band and other nearby tissues.

There are multiple ways to do this. The best results are often achieved by treatments from a qualified professional, such as a physical therapist. However, if you want to treat your IT band yourself, my favorite method (which is somewhat uncomfortable — but often very effective) is to use a barbell sleeve as a rolling pin up and down your IT band. It’s not the only thing I do to treat the issue, but it’s an adjunct that can be pretty effective.

If this isn’t ideal for you, you can opt to try:

- Foam rolling

- IASTM

- Compression flossing (Voodoo flossing)

Issue 3: Non-muscular tissue

With all the different structures and tissues in the body, there’s no rule saying that your knee pain can’t be coming from structures other than muscles. What follows are some other common non-muscular conditions that can cause knee pain when performing leg curls or other knee bending movements.

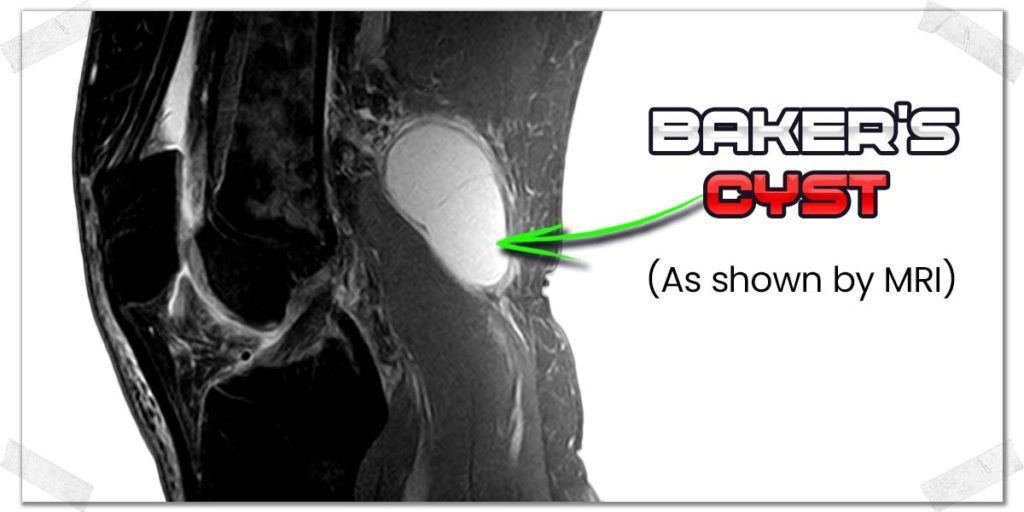

Baker’s cyst

A baker’s cyst is a collection of fluid that can form on the backside of the knee. The fluid is from the synovial fluid within the knee that has herniated from the joint’s synovial membrane and collected on the backside of the joint. The result is often sensations of pain, discomfort or tightness on the backside of the knee.

Baker’s cysts are often benign and usually respond well to conservative measures. If you want the full-meal-deal on baker’s cysts, check out the following article on physio-pedia.

Pro tip: In otherwise healthy adults, a Baker’s cyst can signify another underlying pathology (issue) in the knee, such as osteoarthritis or a meniscal tear. So, if it’s confirmed that your knee pain or discomfort is from a Baker’s cyst, you’ll want to work with a healthcare professional to determine if there’s anything else going on within your knee joint.

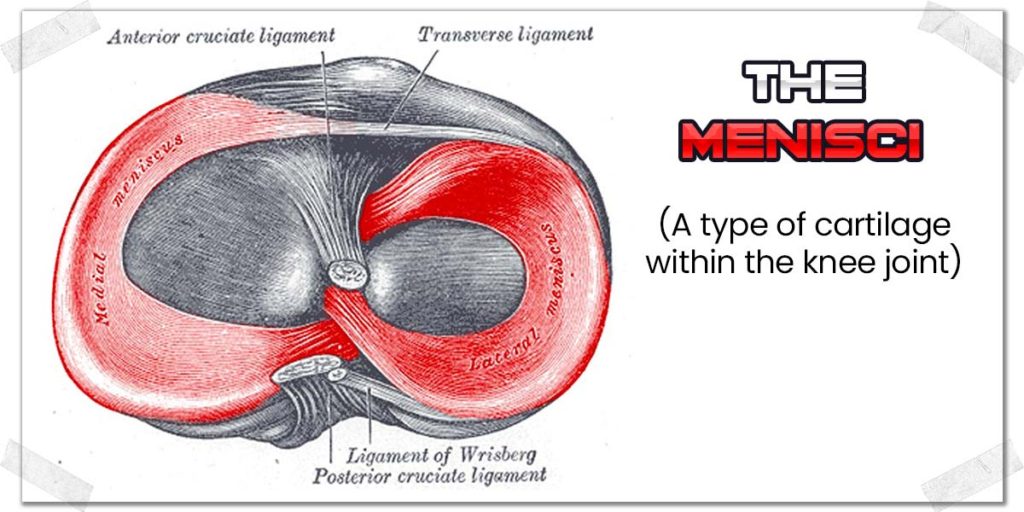

Meniscal injury

The menisci (singular = meniscus) consist of two cup-like cartilage structures that sit in the knee between the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia). Their role is primarily to provide shock absorption to the joint with our weight-bearing activities.

Like any other structure in our body, the meniscus can become a bit scuffed up or even torn. When this happens, pain is often felt around the knee joint, particularly with movements involving bending of the knee.

Menisci can be a bit tricky to work with, but they do have a certain propensity to heal up under the right circumstances.

If you want more details, I’d start by reading this scientific article:

Arthritis

Arthritis of the knee (known as osteoarthritis) tends to become more common as we age (it’s most common around the fourth decade of life and thereafter). It’s a degenerative condition that involves the breakdown of the joint’s surfaces (the cartilage), leading to pain and dysfunction within the joint.

Though it typically is felt more on the inside portion of the knee (at least, initially), arthritic knee pain can show up (present) just about anywhere in the joint, so it’s worth briefly mentioning in this article. If your knee is arthritic, you’ll want to become familiar with ways you can keep on exercising without provoking or worsening your knee pain in the process.

Nerve tension

While typically not explicitly confined to the back of the knee (it’s typically felt along the back of the thigh and down into the back of the knee), nerve tension from the sciatic nerve is briefly worth mentioning.

Nerves are not any different from other tissues (such as muscles) in our body; they are prone to becoming sensitive, irritated, and as a result, restricted in their ability to move as freely as possible. This is known as dural tension. In the case of the sciatic nerve, it can produce sensations of tightness or discomfort down the back of the leg and, subsequently, the knee.

If you’re dealing with nerve tension, your best bet is to get to the root cause of the issue (it can often be the result of radiculopathy from an issue in the lower back). Get a professional evaluation for this, and consider implementing some neuromobilization exercises to help restore optimal dynamics to your nerves. Check out the video below for a bit more insight on this.

Final thoughts

If you’re experiencing knee pain with any type of leg curl or other hamstring-dominant movements, you’re best off to figure out why the pain is occurring, then make the necessary modifications and adjustments to your exercises and physical activities as you work to resolve the issue. Don’t be afraid to get insight and guidance from a qualified professional to ensure that you get back to pain-free leg curls as quickly as possible.

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!