When performed correctly and on the right individual, the deficit deadlift can yield benefits that are hard to replicate through other exercises. But when performed incorrectly or on the wrong individual, it can be devastating to near equal proportions. In this article, you’re going to learn the essential details required to master this exercise and whether or not it’s appropriate for your body in the first place.

Back pain from deficit deadlifts is most often due to rounding (flexion) of the lumbar spine, poor hip mobility, and using too high a platform for the deficit. Solutions involve:

- Optimizing deficit height.

- Ensuring proper lumbar spine position.

- Improving hip mobility.

- Lifting an optimal load.

Of course, there’s a lot to unpack within this article. Read each section below if you want to avoid the mistakes that have landed some lifters in serious pain (whom I’ve seen and treated firsthand)!

ARTICLE OVERVIEW (Quick Links)

Click/tap on any headline below to immediately read that section!

• How’s your hip mobility?

• Lumbar spine positioning

• Selecting optimal deficit height

• Is the deficit deadlift for you?

Related article: Why Russian Twists are Hurting Your Back (And What to do About it)

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including pain from deficit deadlifts. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

A quick note: As we go through this article, keep in mind that I’m approaching it with the belief that you’ve been performing your deficit deadlifts (and, subsequently, been getting pain) with moderate-to-moderately heavy loads (north of 65% 1RM), or even heavy loads (north of 80% 1RM).

If you’ve been getting back pain with pulling very light or even just light loads, it’s likely a good idea to forego the deficit deadlift for the time being until you have a proper evaluation of your back.

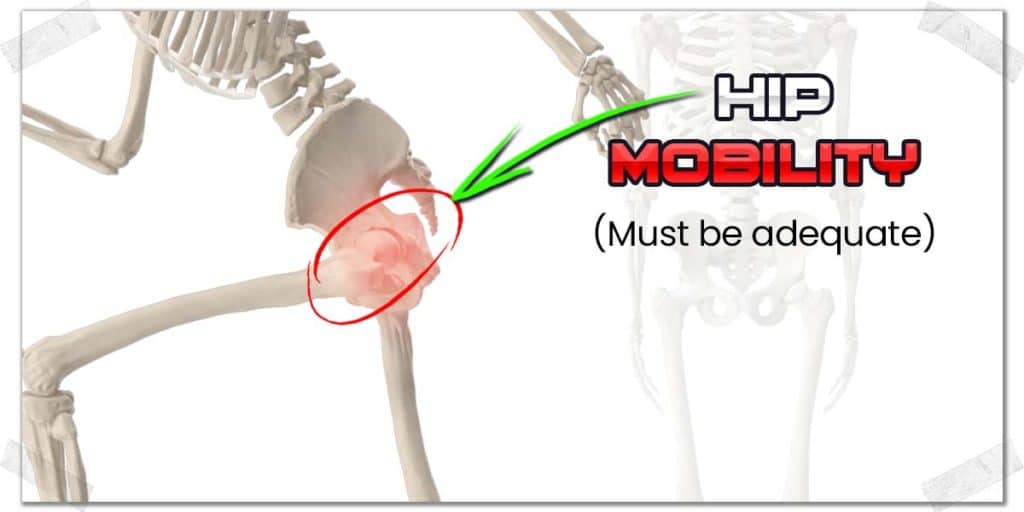

Hip mobility requirements

You might not be aware of this, but the deeper you drop your butt to the ground in the deadlift, the more mobile your hips need to be. The hip is a ball and socket joint, and flexing (bending) of the hip causes the ball to roll within the socket. The less the ball can roll (due to stiffness or tightness).

If your hips don’t have adequate mobility, your body will make up for this lack of movement by forcing the movement to occur in another area of the body. (This is known as movement compensation.) In the case of the deficit deadlift, the less mobile your hips are, the greater your lumbar spine will need to flex to allow you into the deficit deadlift position.

Related article: The BEST Glute Medius & Minimus Exercise That No One is Showing You

It’s the same phenomenon as deep squats, which you might be familiar with; if your hips don’t have the required mobility for the bottom position of the lift, your lumbar spine will flex (round), leaving you with the infamous butt-wink, which leaves the spine in a vulnerable position if then subjected to heavy loads.

The fix for lousy hip mobility

If your lower back has been feeling a bit dodgy after some deficit pulls, start by assessing the mobility of your hips. If you already know that you have tight hips, you’ll either need to modify or forego your deficit deadlifts or start working on reclaiming your hip mobility.

As you work to free your hips from their lousy mobility, consider putting your deficit deadlifts on hold for the time being. Switch back to pulling off the floor without the deficit, or consider pulling from the rack or blocks if your mobility is really lousy.

Lumbar spine positioning

This section is essentially a continuation of the previous section since the lumbar spine and the hips — while anatomically separate areas — are functionally intertwined; when one starts acting up, the other quickly follows.1,2

If you can’t hold your spine in a neutral (flat) position when setting up in the deficit position, it’s not worth pulling the weight off the floor (assuming it’s a moderate — or heavier — load.

Repeatedly lifting heavy weight off the floor with a flexed lumbar spine is asking for trouble with the lumbar discs and sometimes the facet joints as well. I’ve seen (and treated) way too many strong and talented lifters who make this mistake. You might be able to get away with it in the short term, but it will very likely come back to haunt you in the long term.

The fix for correcting your lumbar spine position

You need to have pristine lumbar spine positioning at all times throughout the deficit deadlift (or any deadlift, for that matter) if you’re going to be pulling heavy loads. Not only that, you need to have total confidence in your spine’s positioning at all times throughout the lift.

The solution is to set yourself up in the deficit sideways to a mirror. Set yourself up in your starting position and turn your head to look into the mirror to determine if your spine is in a neutral (straight) position or if it’s rounded. If you can’t consistently get your spine into a neutral position (and maintain it thereafter), reduce the deficit height or ditch it altogether.

Practice as much as needed until you can achieve perfect positioning without relying on a mirror to check your positioning. Once you’re fully confident and can nail the position every time, you can then consider pulling from the deficit position again.

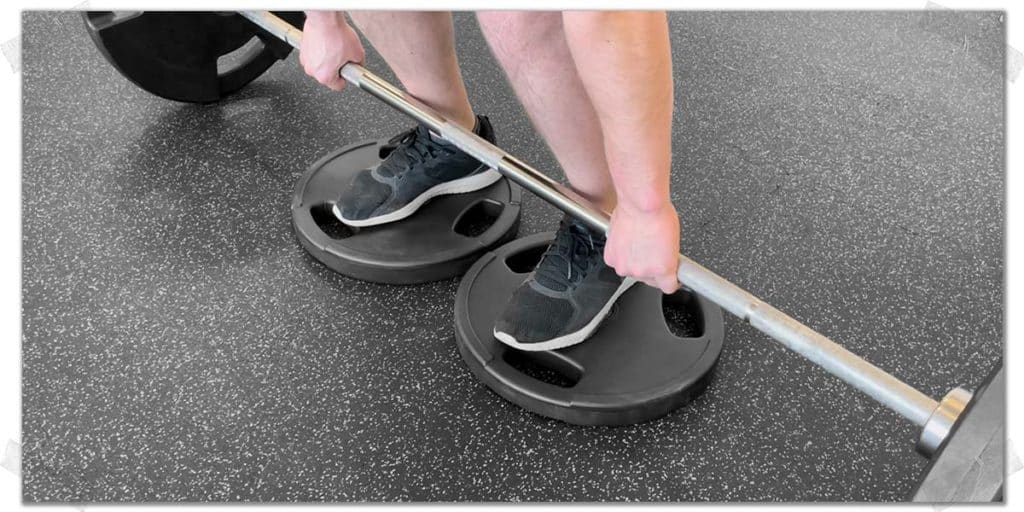

Selecting optimal deficit height

When it comes to the deficit deadlift, too many lifters make the mistake of thinking, “if some deficit is good, then more must be better.” This couldn’t be further from the truth.

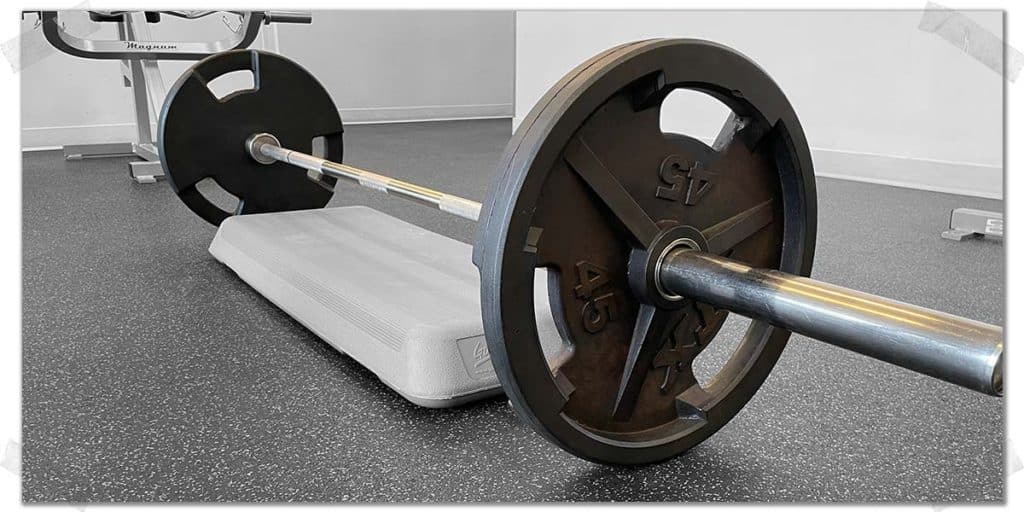

The purpose of the deficit deadlift is to put you at a slightly greater mechanical disadvantage than when lifting off the floor, not a massive one. It doesn’t take more than an inch or two for a noticeable mechanical disadvantage to be produced.

Unless you are lifting with extremely light loads and are using the deficit deadlift more for a mobility exercise than a strengthening one, a deficit of no more than two inches should suffice.

Some lifters might have naturally great mobility and could get away with more, but even then, I personally wouldn’t recommend it, assuming you’re still pulling loads heavier than around 65% of your one-repetition maximum. Cap it at two inches.

Building up to the optimal height

The “optimal” height for each lifter will likely be different depending on numerous factors pertaining to their own body, training goals, and overall training age.

Nonetheless, if you’re not sure what an optimal height for you might be, here’s a general progression I’d recommend to find out what your body tolerates best:

- Start by doing a couple of weeks of pulling off the floor sans deficit. Do this to make sure that your back can at least tolerate weight off the floor from traditional heights. If you can do this without your back flaring up, then move on to the next step.

- Take another week or two and pull anywhere from a 0.5″ to 1.0″ deficit. Standing on a cut-up piece of plywood can work well for this. If you’re lifting in a public gym, see if you can stand on some metal 5lb or 10lb plates (assuming they’re flat and won’t move around on you). These plates are usually around half to three-quarters inches thick. The other option is to stand on thin bumper plates, if available within the facility.

- If you experience pain or discomfort with this deficit, move back to pulling without a deficit until you get to the root cause of your discomfort. If you can pull from this height for a week or two without any issue, move on to the next step.

- Bump it up to anywhere from another half, three-quarters, or full inch if you still feel the need to pull from a more aggressive deficit. You can stay here if your back can tolerate this deficit for the next handful of sessions. If it gets cranky, drop the deficit height back to the previous level until you get your back under control.

Is the deficit deadlift for you?

Not everyone is built to pull weight from a deficit, or even from off the floor, for that matter. Numerous factors can determine whether deficits are a good idea for a lifter. The main factors include:

Hip structure and composition

Despite what you might have been told, not all hips are created the same; a handful of factors can influence the natural mobility and positional preferences that your hips may have.

Some of these factors include:

- Hip socket depth

- The angle of inclination of the neck of the femur

- Conditions such as femoral acetabular impingement (FAI)

Ultimately, factors such as these can significantly influence the natural rages of motion your hips may have or the positions which might be irritating or uncomfortable for the joint.

Remember, the less mobile your hips are, the harder of a time you’ll have with keeping your back in a strong position for the deadlift, which can lead to various forms of back pain.

If you feel your hips won’t let you hold proper positioning while doing deficit deadlifts, despite your best efforts to improve their mobility, it may be due to how your hips have been put together (blame your parents for this one). If this is the case, and your back constantly feels tweaked from deficit pulls, you may be best off to forego pulling from a deficit position.

Previous injury & overall mobility

If you’re someone who has a history of hip injuries or has some banged-up joints that are constantly painful or have lousy mobility, it might be in your best interests to put your deficit deadlifting on pause while you work on improving the health and mobility of your hips.

If you can restore your hip health to the point of adequate mobility and no pain when pulling weight off the floor, then it’s likely fine to get back into routine deficit work. But don’t sweat it if you can’t — there are still numerous other exercises you can likely implement if the deficit pull just doesn’t work for you.

Related article: Six Benefits of Using An Acupressure Mat For Your Aches and Pains

Training age and training goals

While the deficit deadlift isn’t much more technical than a floor-height deadlift, it still requires a relatively high level of technical execution. As a result, if you’re not proficient with pulling weight off of the floor from a standard height, I’d advocate that you master all aspects of your form and technique from pulling from the floor before pulling from the deficit.

If you’re somewhat new to training (i.e., have a young training age), you will make plenty of gains with traditional deadlifts, so don’t think you have to pull from a deficit to become stronger.

Additionally, you’ll be just fine without deficit deadlifts unless you’re training for very specific goals (and have an advanced training age). Traditional deadlifts will work just fine for you if you’re just looking to become stronger, more robust, and healthier overall.

Final thoughts

The deficit deadlift is undoubtedly a powerful variation of the deadlift; it has numerous benefits that can do wonders for the right individuals. But it’s certainly not an exercise for everyone. If you find that this exercise constantly tweaks your back, get to the root cause of the issue rather than just trying to push through. And don’t sweat it if this exercise is one you have to forego — some people’s body’s just don’t tolerate it all that well. And if that happens to be you, remember that there are plenty of other deadlifting variations to try aside from the deficit deadlift.

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!