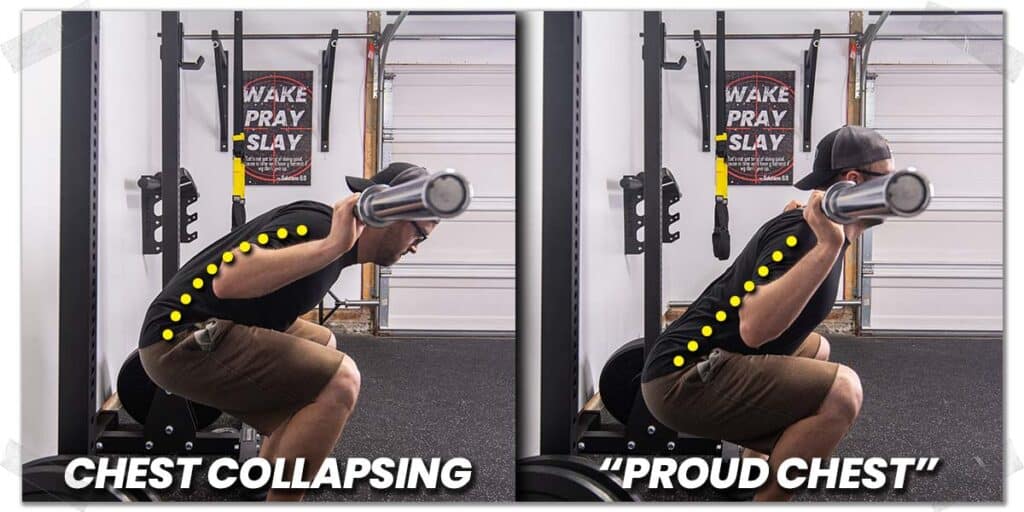

When it comes to building a strong set of legs, squats are a foundational exercise to perform. But they’re not worth performing if you can’t keep your chest up throughout the movement; at best, you’ll have lousy squats, and, at worst, you’ll get injured.

Not being able to keep your chest up when squatting is a relatively common issue, and it can occur for various reasons. This article will walk you through the most common reasons why lifters often struggle to keep their back straight and their chest up when performing the squat.

Lifters often have difficulty keeping their chest up when squatting due to issues in their thoracic spine, lousy hip mobility, poor foot positioning, and poor motor control. Optimizing mobility throughout these regions and improving squat mechanics can make a profound difference.

So, let’s get right to it and dive into the causes and solutions for this “chest challenge.” Take the time to read the entirety of this article. You’ll walk away with the knowledge required to recognize why this issue is likely occurring and the effective strategies you can use to overcome this problem altogether.

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

As I dive into things here, remember that human beings are all different enough that there’s always room to individualize the squat to meet each lifter’s needs, abilities, and factors unique to their overall circumstances.

For example, the amount of “chest up” positioning a lifter uses can vary based on numerous circumstances, and what might work for one lifter might not for the next.

So, as we dissect and discuss this common training issue, take the following concepts and information and plug them into your training in ways that work best for you!

Related article: Locking Your Knees When Squatting: Good or Bad? (Detailed Breakdown)

The Big Deal: The premise behind “chest up”

The premise behind keeping the chest up when squatting is that it keeps the lower and upper back in a stronger and safer position throughout the movement.

The strength aspect comes largely from an optimized center of gravity, leading to improved biomechanical leverage from the hip joint and muscles within the body.

The safety aspect comes from reduced strain on the lumbar spine’s intervertebral discs and reduced torque and stress on the surrounding muscles (erector spinae muscles, the multifidi muscles, etc.).

It’s hard to bang out heavy squats when your body doesn’t capitalize on optimizing leverage, and it’s even harder when your back hurts and you’re writhing in pain.

That’s where the “chest up” cue comes into play; it can help many lifters offset both issues simultaneously.

Just remember: the expectation is never to keep the chest perfectly upright when descending into the squat (some lifters can do this due to the anatomical configuration of their hips, but it’s not overly common). Rather, it’s best to focus on maintaining a slight forward lean at your torso while preventing your upper back from rounding.

Alright, let’s look at the most common issues regarding the inability to keep your chest up during the squat and how the problem can often be solved.

Issue 1: Thoracic spine stiffness (lacking extension)

The thoracic spine has a reputation for causing positioning issues and technique errors with the squat. Issues can arise elsewhere in the body, mind you (which will be discussed shortly), but since most people think of the thoracic spine region when dealing with the “chest-up” battle with squats, perhaps it’s best to start here.

For those unaware, the thoracic spine refers to the twelve vertebrae between the cervical spine (the neck) and the lumbar spine (the bottom five vertebrae in the back).

The thoracic spine itself is capable of producing movement in pretty much every direction, though the two movements that we need to focus on when dealing with a chest that can’t stay upright when squatting are:

- Flexion

- Extension

Flexion is the movement your thoracic spine produces when you round your upper back. Extension is the movement it produces when you straighten it.

The thoracic spine doesn’t produce much natural extension, but it has a high capacity for flexion. Combine this with the natural torso position that the squat requires a lifter to maintain and one soon realizes it’s a lot easier to let the upper back round (causing the chest to collapse downward) than keeping it straight and facing in a relatively upright position.

“The amount of ‘chest up’ positioning a lifter uses can vary based on numerous circumstances, and what might work for one lifter might not for the next.”

Solutions for thoracic spine issues during the squat

Assuming you don’t have any underlying congenital issues that make it difficult to straighten your thoracic spine (such as a naturally high degree of kyphosis or Scheurerman’s disease), your best bet is to implement a dedicated spinal “hygiene” program that helps you to improve and maintain mobility with your facet joints (the intervertebral joints that link up one vertebra to the next).

A spinal “hygiene” program can include interventions such as:

- Foam rolling the thoracic spine to help mobilize the facet joints.

- Mobility exercises that help to improve thoracic extension.

- Soft tissue treatments (such as massage) to reduce muscle tension.

To get a head start on improving your thoracic spine mobility, check out my YouTube videos below:

Issue 2: Hip restriction or poor foot placement

Believe it or not, the hip can play a prominent role in your overall upper-body mechanics when squatting, especially with the ability (or lack thereof) to keep your chest up as you descend into the movement.

Here’s why:

Squatting is a combination of knee flexion (bending) AND hip flexion. Without adequate amounts of both movements, the squat pattern breaks down. Most individuals can picture how this breakdown occurs with stiff knees but may have a harder time picturing what happens when the hips are stiff. So, let’s walk through this.

Understanding how hip dysfunction impacts the squat

Hip flexion (the forward bending of the hip) results from the ball of the femur (thigh bone) spinning in the hip socket—and this is the exact movement that occurs during the squat.

When the hip joint becomes stiff (which can occur for numerous reasons), it can’t spin in the socket to the same amount as if it were not stiff.

Once the hip runs out of its available range of motion when descending in the squat, the joints in the lumbar spine (the bottom five vertebrae in the back) will begin to flex forward, causing the lower back to round.

Lumbar (low back) flexion will allow you to move deeper into the squat, but it will come at a cost to your squat form and technique.

When the lower back rounds, the thoracic spine, and therefore, the chest, tend to follow this path, causing the chest to drop down toward the floor. In this case, the chest not remaining in an upright position is not the fault of the thoracic spine or upper body itself but rather from the limitation of the ball and socket joint within the hip(s).

In this regard, the back is merely the victim, while the hip joint is the culprit.

So, the solution is to improve your limited hip mobility, allowing your chest to stay in an upright position as you descend into the squat. Wild, right?

So, let’s dive into how to clean up any mobility restrictions that are present within your hips, which will improve your squat technique.

Solutions for hip restrictions when squatting

The starting point for dealing with tight or restricted hips (or just a singular hip) is to determine what’s causing the restriction. Typically, the hip can experience poor mobility due to either:

- An issue within the joint itself (such as osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, etc.)

- An issue with the structures surrounding the hip (such as the joint capsule of the hip or the muscles crossing the hip joint)

It’s important to know what’s causing any impairments in your hip mobility since the treatments or interventions required to improve the condition can be quite different.

Your best bet here is to get an assessment from a qualified healthcare professional who can determine what’s causing your poor hip mobility and show you the best way to start making improvements.

“When the lower back rounds, the thoracic spine, and therefore, the chest, tend to follow this path, causing the chest to drop down toward the floor.”

If your hip doesn’t want to move due to an issue with the actual joint itself (issue 1) or osteoarthritis or hip socket abnormalities (such as a labral tear or bony overgrowth of the hip socket — a condition known as acetabular impingement), then you’ll certainly want to work with a qualified healthcare practitioner to determine how best to proceed (ideally someone familiar with strength training); these scenarios will likely require additional measures to correct the underlying problem.

However, if you’re certain the issue is purely due to tight muscles or a stiff joint capsule, there’s likely a fair amount of mobility improvement to be had — if you’re willing to be patient and persistent with some dedicated hip mobility work.

Since hip stiffness is such a common issue among lifters, I’ve included two solutions worth considering and implementing, both of which can make profound differences in helping lifters keep their chest up when squatting.

Keep on reading to learn more about these solutions!

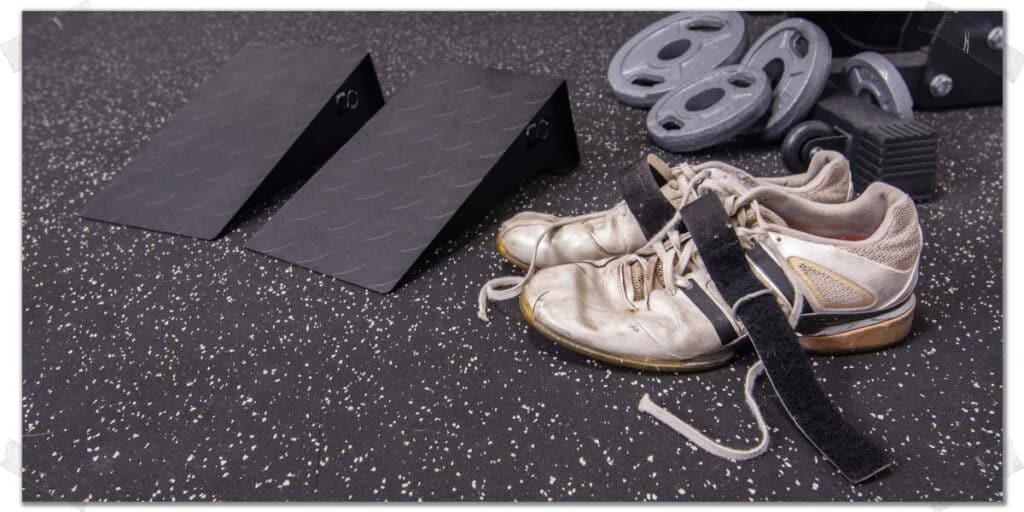

Solution 1: Using squat wedges & lifting shoes

Squatting with wedges underneath your feet can work wonders to help keep your chest upright during the squat. There are two particular ways in which this can be incorporated into your training sessions:

- Using dedicated squat wedges (often called heel wedges)

- Wearing weightlifting shoes (which have a heel wedge built into the shoes themselves).

Whichever you pick, you’ll likely notice that having your heels resting on an elevated surface makes it much easier to keep your torso and chest upright. This is due to the shortening of the posterior chain (muscles along the backside of the body).

To read up more on how and why this strategy works and what to be aware of (the good and the bad), check out my squat wedge article below:

Solution 2: Modify your squat stance

Everyone’s hips are put together slightly differently. While these differences may seem rather innocuous to the average individual, if you understand human anatomy well enough, you’ll know they’re enough to change movement abilities and squat mechanics from one individual to another, depending on how things are put together.

Without going into the weeds here (discussing the geeky details such as femoral anteversion and retroversion, acetabular socket depth, femoroacetabluar impingement, etc.), it’s important to realize that one’s squat stance can have a profound impact on upper-body positioning during the squat.

Despite what other lifters might tell you, there is no universal “best” stance for squatting. Yes, some positions may be more ideal in terms of generating more force, better stability, etc. Still, these positions may differ slightly from one individual to the next based on their individual hip configuration.

Here are some squat stance modifications you may want to consider experimenting with in terms of seeing if they can help correct and, thereafter, maintain an ideal upper-body position when you squat:

- Consider playing around with your toe angle or “flare.” Pointing your toes slightly outwards when squatting tends to open up the hips a bit more to allow for a greater degree of hip flexion, which can help keep your torso more upright.

- Consider experimenting with the width of your squat stance. Some lifters might find a wider stance to be more advantageous, while others might find it more ideal to maintain a slightly more narrow stance.

Issue 3: Hips rising too early

For some weightlifters and athletes, the inadequacy of their hip mobility isn’t the issue; the issue is keeping their hips down when ascending from the bottom of the squat.

This is often referred to as “hip shooting,” where the hips shoot upwards at a quicker rate than the chest and shoulders. When this happens, the chest begins to point toward the ground, making for a highly inefficient squat (and not the safest one, either).

When performing any type of squat — barbell back squats, front squats, goblet squats, split squats, etc. — the hips and shoulders should always rise upwards at the same rate when ascending from the bottom of the movement.

The greater the hips rise upwards in relation to the upper body, the more the chest will point towards the floor.

The solution for keeping your hips down

For most lifters whom I’ve worked with over the years, the solution for keeping the hips from rising too early when squatting is to simply be mindful of this occurring; I often have athletes and clients who are unaware of the mismatch occurring between their hip and upper body ascension during the squat.

Just remember: you want your hips and shoulders to rise and descend at the same rate when squatting.

If you’re not sure if this is happening, you can either have a friend observe a few of your squats and let you know, or you can video yourself on your phone and then watch for yourself to see if your hips are “getting away from you.”

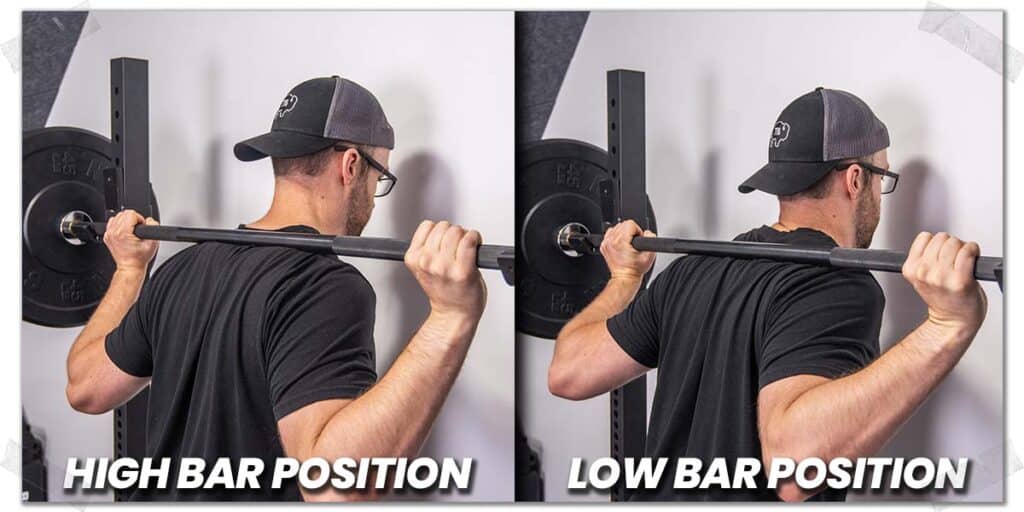

Squat Technique Considerations: High bar vs. low bar

If you’re not aware, there are two different bar placement techniques for the back squat. They are:

- High bar technique

- Low bar technique

The placements involve exactly what their names imply; the high bar technique involves resting the barbell on a higher portion of your back (typically just below the C7 vertebra), while the low bar technique involves resting the bar around the fourth thoracic vertebra (T4).

Some lifters find that the low bar technique is more ideal for helping keep the chest up during the squat. This can be attributed to the barbell resting lower on the thoracic spine, which not only changes the center of gravity on the lifter (it shifts it backwards) but also helps to lock the thoracic spine into extension, preventing it from bending forward.

Additionally, the low bar position forces the squatter to naturally push the chest out (which flattens the upper back, preventing it from rounding) as a means to maintain the shoulder position required to grab the bar.

Most powerlifters and strongmen competitors prefer the low bar technique for a few key reasons (beyond the scope of this article), though this isn’t a universal case.

“The greater the hips rise upwards in relation to the upper body, the more the chest will point towards the floor.”

Contrast this with the high bar technique, where this bar position shifts the lifter’s center of gravity forward, and the shoulder position required to grab the bar doesn’t require as much external rotation or scapular retraction (pulling the shoulder blades backwards). The less these shoulder movements are required, the less the thoracic spine is forced into extension.

There’s no universal “right” or “wrong” for which bar position is most ideal for your needs; you’ll need to experiment and see which one works best for you. As such, take the time to experiment to see which one is most ideal for maintaining an upright torso when squatting.

Make the change: Switch to front squat (pros & cons)

If the barbell back squat is proving to be too much of an issue for maintaining an upright chest position, it may be worth switching over to the barbell front squat. If given the right cues, it may actually be easier for some lifters to maintain a more upright torso with the front squat than with the traditional back squat.

However, it’s worth noting that the idea of implementing the front squat may backfire a bit; some lifters may find it harder to keep their chest upright with this squat, so play around with the following technique for a bit, but don’t sweat it if it’s just not working for you.

The key to keeping the chest upright when front squatting is to drive your elbows upwards as you move lower into the squat.

This cue works best when performing the traditional front squat but still also works when using the California grip (the crossed grip).

This is a cue that has worked wonders for those whom I’ve trained over the years. The further down the lifter moves into the squat, the more they’re cued to drive their elbows upward, which does wonders for ensuring they keep their upper back straight and their chest pointed upward throughout the entire movement.

RELATED CONTENT:

Final thoughts

Ensuring you can keep your chest from dropping towards the ground when squatting is a crucial ability for every lifter to have. If your chest is pointed more at the floor than in front of you throughout your squat, you’re asking for poor squat performance and—much more critically—problems with your back.

Use the tips and insight in this article to work on improving your squat technique in a manner that keeps your chest up and your squat sessions effective!

Frequently Asked Questions

To help answer a few additional squat-related questions that activity individuals tend to have, I’ve included a few brief answers below to some commonly asked questions.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!