It’s an odd — and very annoying — feeling to have one hamstring that’s chronically tighter than the other, especially if you don’t know why it’s happening. And if you don’t get to the bottom of the issue, it can plague you (and even worsen) with pain and dysfunction for years to come. Thankfully, by the time you finish reading this article, you’ll have a solid understanding of how and why this condition can occur and how to go about solving it once and for all.

One-sided hamstring tightness is often the result of previous injury, sciatic nerve tension, lower back dysfunction or immobility of the hip joint. Solutions involve strengthening and mobilizing affected tissues, correcting structural issues and eliminating faulty movements of the hip and back.

Now, if you’re serious about wanting to know the exact specifics of how to get your hamstring under control, you’re gonna have to know more than just the quick summary. So, if you genuinely want to tackle this issue, keep on reading.

ARTICLE OVERVIEW

Click/tap on any of the headlines below to instantly read that section!

• Relevant anatomy (must know)

• Taking a personal history

• Differentiating tissues

• Dealing with sciatic nerve tension

• Dealing with muscle tissue

Related article: No Equipment Required: This Hamstring Exercise Will Light You Up!

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including dealing with hamstring tightness or pain. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

Relevant anatomy (must know)

Having a baseline understanding of anatomy within the region of the posterior hip, thigh, and lower back will help you better understand why you might be dealing with your hamstring issue. It will also help you realize why you must consider certain factors and take precise actions to remedy the underlying cause. So, let’s quickly run through what is pertinent for you to know.

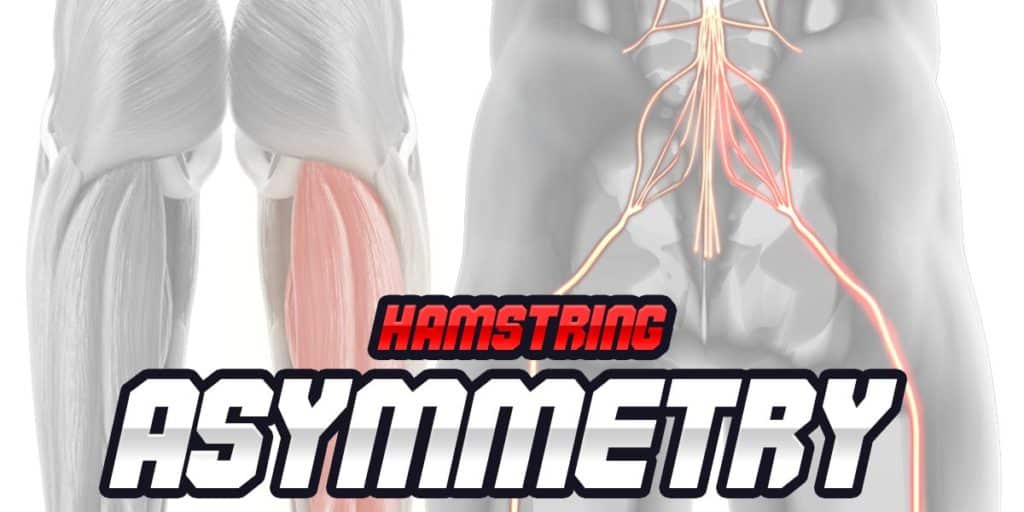

The two most critical anatomical structures to be aware of are the hamstring muscles and the sciatic nerve (if you want to know why, read the entire article).

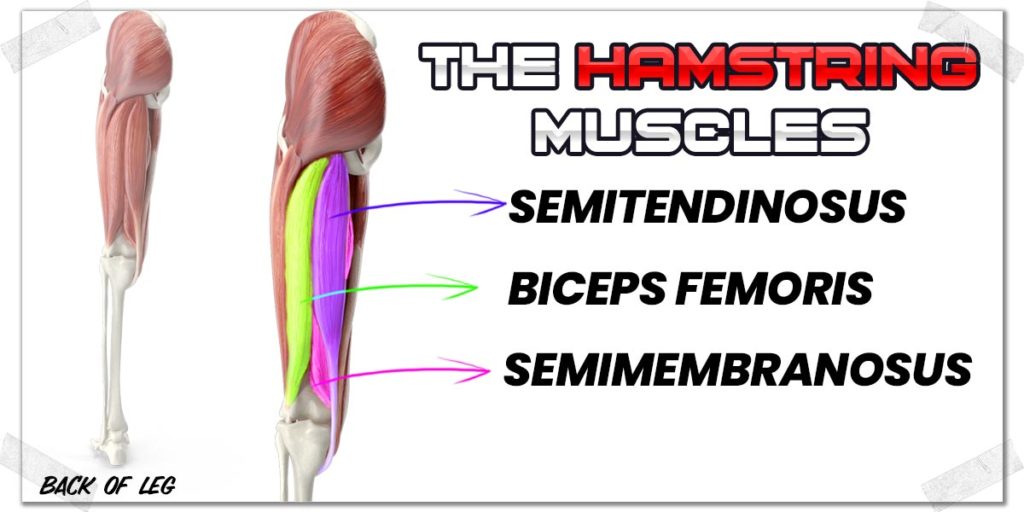

The hamstrings

The hamstrings are comprised of three individual muscles. They all originate from an area on the bottom of the ischium (the sit bone) known as the ischial tuberosity. Each one then travels downwards to insert on the tibia (shin bone) just below the knee joint (the short head of the biceps femoris, however, inserts onto the head of the fibula).

The hamstring muscles are:

The collective action of the hamstring muscles is to flex (bend) the knee and extend (straighten) the hip, though not necessarily at the same time. Since the hamstrings cross two joints (the knee joint and the hip joint), they can produce movement at either of these two joints.

Related article: Six Benefits of Using A Glute-Ham Roller (Here’s Why You Need One)

Conversely, stretching of the hamstring muscles occurs either with flexion of the hip (bending forwards) or when extending (straightening) the knee. While producing either of these movements will provide some stretch to the hamstrings, the most significant stretch to the hamstrings occurs when the hip is flexed and the knee simultaneously extended (due to the phenomenon of passive insufficiency).

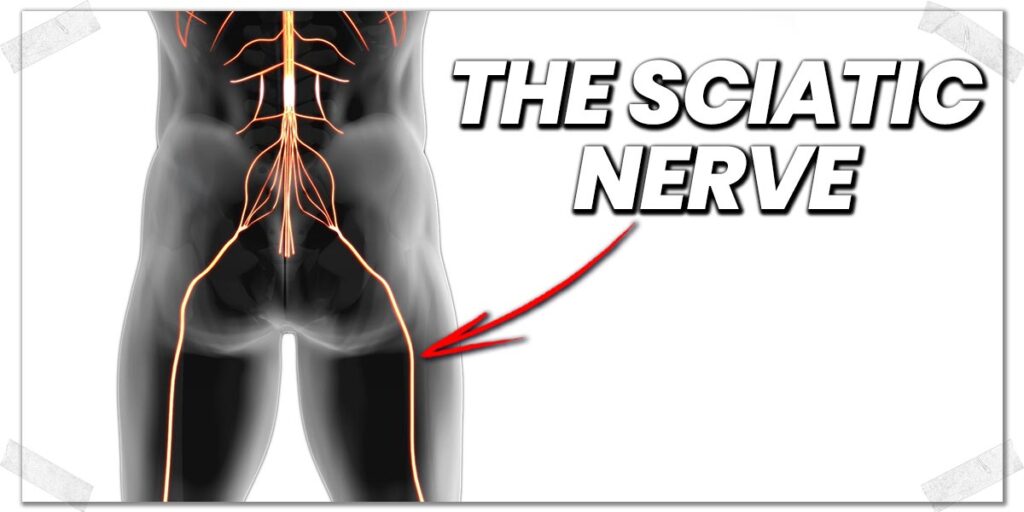

The sciatic nerve

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the human body. It arises from different nerve roots (L4 – S3) exiting the spinal canal and converging together, forming the nerve. It runs down the entire length of the back of the leg all the way down to the foot. The function of this nerve is to supply the posterior (backside) of the leg with motor and sensory function, meaning it provides us with the ability to move and feel the backside of our leg.

Taking a personal history

Scientific literature has found that previous injury and asymmetrical movement from one side of the body can both be predictors of physical injury.1,2 As a result, getting to the root cause of what might be driving (or at least contributing) to your one-sided hamstring tightness should start with a trip down memory lane to ask yourself if you’ve ever injured or irritated your hamstrings, hip, or lower back in the past.

If you’ve ever injured this area of your body in the past, there’s a moderate-to-high probability that your current tightness is related to that particular event. Even if you felt that you had entirely recovered from the issue, underlying dysfunction or inadequate tissue health likely remained in some capacity, likely at a sub-detectible threshold.

As an example, if you had a moderate pull/strain of your hamstring muscles in the past, it’s more susceptible to becoming irritated or re-injured as you continue on throughout life. It’s not a guarantee, mind you. Still, there is a correlation between the severity of the previous injury and the likelihood of re-aggravating or injuring that same body part in the future, especially when it comes to the hamstrings.3

Considering the low back and hip joint

Even though your discomfort, tightness or generalized issue might only be felt on the back of your thigh, it’s imperative that you examine how your lower back and hip are moving. Poor movement control or mobility (or both) can be contributing to the underlying cause of your one-sided hamstring tightness.

The reasons for this are numerous. However, I’ll touch on two of the most common reasons for lower back and hip dysfunction contributing to single-sided hamstring tightness. As I do, you must be aware that any single cause of dysfunction can affect multiple tissues (I.e., the hamstring muscles themselves, the sciatic nerve, or both structures simultaneously).

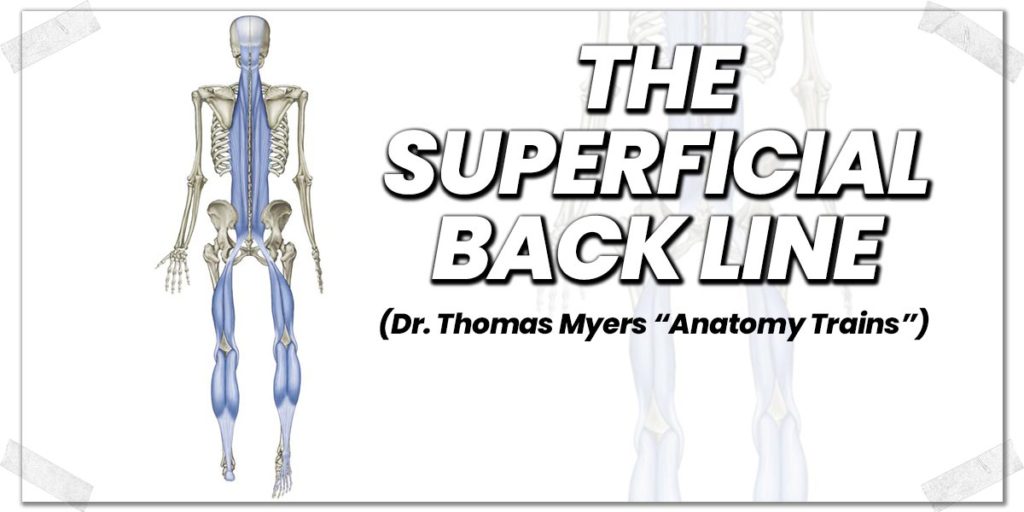

Fascial restrictions along the superficial back line

The body is connected in all sorts of unique and truly fascinating ways. One such example is through a series of fascial connections running throughout the entire body, often referred to as fascial trains or meridians. The challenge with these connections is that dysfunction in one area can travel along the meridian to affect other areas.

There are seven myofascial trains within the body:

- The superficial back line

- The superficial front line

- The deep frontal line

- The front & back arm lines

- The functional lines

- The lateral line

- The spiral line

In the case of a tight hamstring, fascial restrictions in the lower back or elsewhere on the backside of the lower leg can contribute to tightness or discomfort of the hamstring muscles. These muscles are all part of the superficial back line, meaning they have a fascial connection to one another, representing one of the many reasons why it’s imperative that you examine your lower back, hip and entire posterior leg when it comes to determining the root cause of your tension or lack of available movement in the back of your thigh.

If you’re interested in learning more about fascial meridians, the superficial back line, or the world of fascia in general, be sure to check out Thomas Myer’s famous book Anatomy Trains (Amazon affiliate link). Note: Any commissions I earn from affiliate links are used to offset the costs of running this website. Your support is always greatly appreciated!

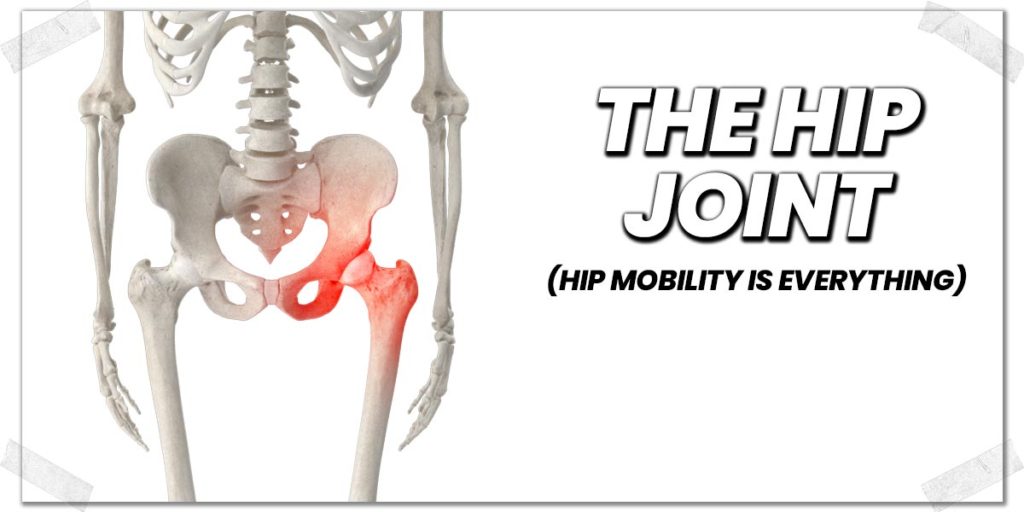

Immobility of the hip joint

The hip joint is a ball and socket joint that provides movement in all directions. If the hip joint itself becomes stiff or immobile (which can happen for various reasons), it cannot go through large or adequate ranges of motion. When this happens, tissues and muscles that cross the hip joint (such as the hamstrings) don’t have to elongate or stretch as a means to accommodate these large ranges of motion. As a result, the hamstrings can lose their “suppleness” or ability to stretch since they’re never taken through larger ranges of motion. Think of it like a rubber band that loses its elasticity.

When this takes place, the stiff, non-supple hamstring becomes much more sensitive to any stretch or elongation that they must undergo, meaning that any time you stretch that particular leg, you feel the stretch occur much sooner than when compared to the other leg.

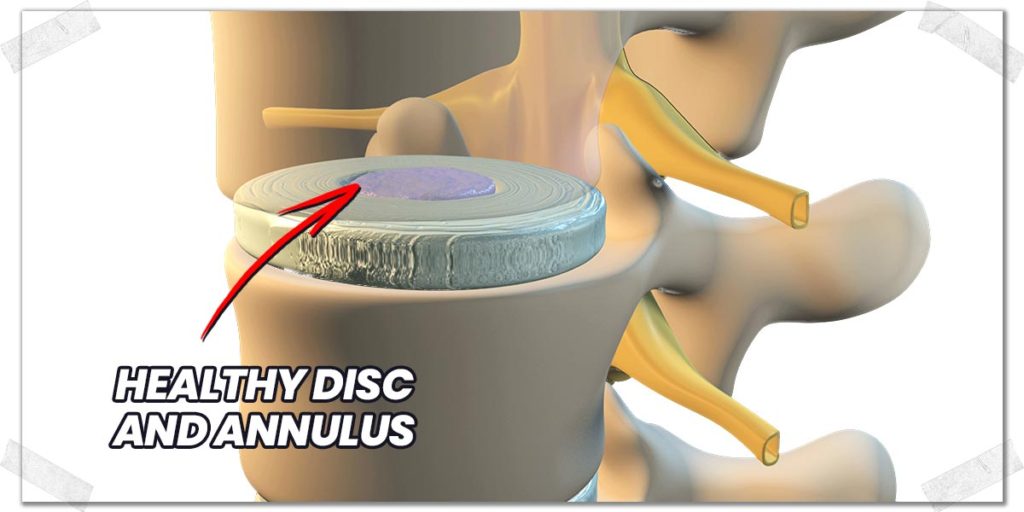

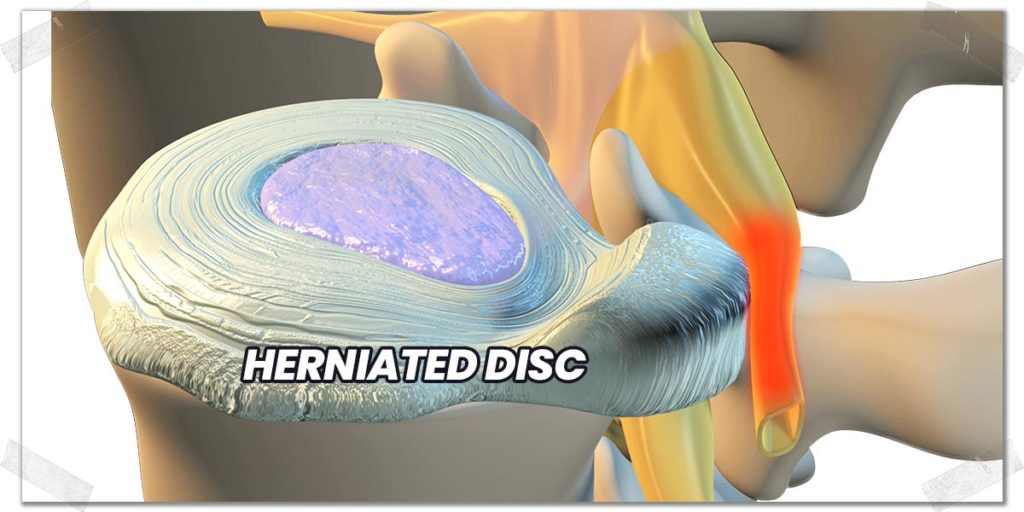

Intervertebral discs

The intervertebral discs of the spine are the hockey puck-like fibrocartilage structures that sit in between each vertebra. Normally, these discs sit directly underneath and on top of the vertebrae. However, the disc can sometimes budge backwards, pressing on a nerve root, which runs right by the disc. When this occurs, the nerve root, and even the entire nerve that it connects with, can become irritated. This leads to a condition known as radiculopathy, which can irritate the sciatic nerve.

In this case, the sciatic nerve can become irritated, which runs down the back of the leg with the hamstrings. So, even though you might feel the greatest amount of tension in the back of your leg, it’s entirely possible that the cause is actually coming from a mechanical issue in your lumbar (lower) spine.

It’s worth noting that a budged disc in the spine typically — though not always — presents with lower back pain. As well, there are times when the lower back pain will subside while the sciatic nerve remains sensitized (extra sensitive) for a prolonged time thereafter.

Spinal stenosis

Any form of irritation to the nerve roots contributing to the sciatic nerve can wind up creating tension within the sciatic nerve itself. In addition to a bulged disc, a second common cause of irritation to any of the nerve roots comprising the sciatic nerve is a condition known as spinal stenosis. Stenosis refers to a narrowing of an opening. In this case, it refers to the narrowing of the intervertebral foramen, which is the opening through which the nerve roots exit through the vertebrae. If there is any physical pressure placed on the nerve roots, it can lead to irritation of the involved neural structure.

Typically, spinal stenosis presents with additional symptoms, such as paresthesia (numbness or tingling) down into the entire leg, or weakness of the muscles controlling the foot or leg. In the absence of injury, spinal stenosis is more common in the fourth and fifth decades of life than in the decades preceding these.

Differentiating affected tissues

Regardless of what might be causing your tightness along the back of your upper leg, it’s essential that you differentiate the type of tissue it has affected. It’s incredibly challenging to quickly and effectively resolve the issue when you haven’t determined the specifics of what has been affected.

While there could be various tissues contributing to your one-sided hamstring tightness or discomfort, I’m only going to address the two most common culprits for the issue at hand, as I can’t address everything in a single article. Still, there’s a moderate-to-high likelihood that one of these two tissues is driving or contributing to your issue.

You must learn to differentiate your perceived tightness between the muscles hamstring muscles themselves and the sciatic nerve, as each of these two structures requires different types of intervention to effectively resolve the issue.

I can’t overstate the importance of this enough. If you have an irritated sciatic nerve that is driving your tightness/movement restriction, trying to stretch it the same way you would with traditional muscle stretching can be like trying to put out a fire by pouring gasoline on it.

So, you must have a clear-cut way of determining which of the two structures is causing your issue. And this is where the slump test comes in.

The slump test

The slump test is an orthopedic test used in clinical practice to determine if an individual’s discomfort or mobility restriction is arising from the hamstring muscles or the sciatic nerve. It’s traditionally done by having an examiner help the individual perform the movement. Still, it’s largely possible to perform the test by yourself — just perform the movement by yourself without having anyone raise your leg for you (it will give similar results).

The test works by winding up the length of the sciatic nerve (taking out any “slack” that the nerve has) to the point of perceptible stretching or discomfort in the back of the leg. The tension of the nerve is then slackened. If the perception of discomfort diminishes or is eliminated entirely, it indicates that nerve tension is the culprit for discomfort or restriction and not the hamstrings.

Conversely, if the slump test is performed and there is no perceptible change in tightness or discomfort in the back of the leg, the discomfort is attributed to a dysfunction with the hamstring muscles or the fascia that covers these muscles.

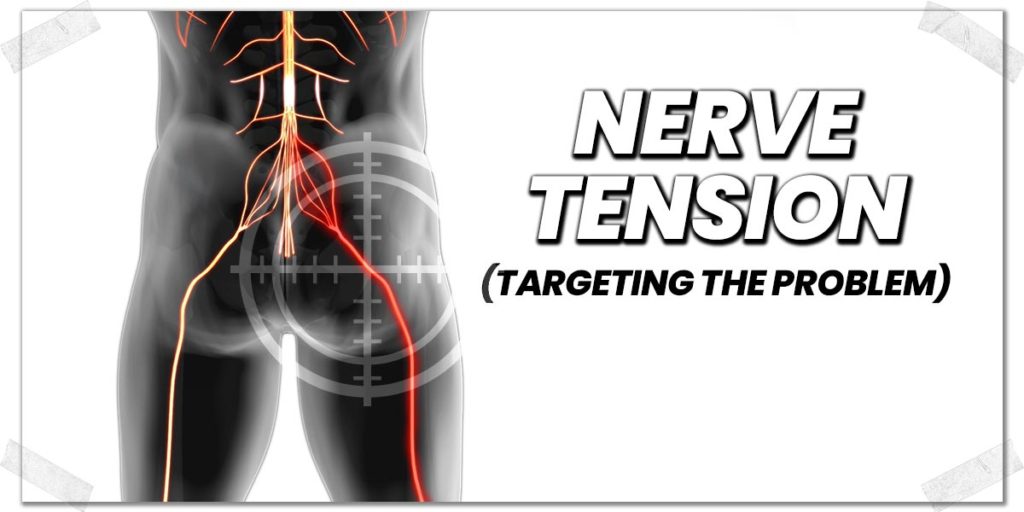

Dealing with sciatic nerve tension

Regardless of what may be the cause of your sciatic nerve tension, your best bet to effectively eliminate the tightness or discomfort is to get the nerve under control through neuromobilizations. This refers to a specific type of movement that helps restore available motion to a nerve. You’ll often hear these movements called nerve flossing or nerve glides.

Irritated nerves don’t like to go through positions that put them on a prolonged stretch. The prolonged stretch makes them extra sensitive (or painful) when they have to lengthen out (such as when bending over). As a result, trying to restore motion to a nerve and calm it down by performing static stretching is pretty much the worst thing you can do if the nerve is highly or moderately irritable (hence why it’s absolutely critical to determine whether your discomfort is coming from the actual hamstring muscles or the sciatic nerve).

While nerves don’t like prolonged stretches, they do enjoy very short-lived stretches that only take the nerve up to the point of tension (but not through it). This is often termed dynamic or undulating movement, where the nerve goes through a repeated wave-like cycle from low to high tension.

Nerve glides have a proven track record of helping irritated nerves — such as the sciatic nerve — calm down and regain their normal range of unrestricted movement, so they’re worth incorporating if you know for a fact (I.e. you’ve been instructed by a licensed healthcare professional) that they’re appropriate for you to do.

Here are some of the most common nerve glides to try for the sciatic nerve:

Dealing with muscle tissue

If you’re confident that your issue is coming from your hamstrings themselves, then there are numerous interventions you can try as a means to restore the overall health, suppleness and range of motion to the muscles. A lot of what your pursuits here will come down to is whether or not you’re willing (or able) to get treatment from a healthcare professional (such as a physiotherapist), or not.

If you’re able to get treatment from a qualified practitioner, some proven methods can include:

- Soft tissue massage

- Active release techniques

- Fascial stretch therapy

- IASTM (instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization)

- Acupuncture or intramuscular stimulation (AKA “dry needling”)

It’s unlikely that the issue will fully resolve within a single treatment, so a few treatments may be necessary. As well, you’d be wise to perform some home exercises or stretches to capitalize on the effects of your treatments that are performed within a clinic. Your healthcare practitioner who treats you will be able to suggest which exercises or stretches would be best for you.

If you’re looking for ways to treat the issue yourself, some of my preferred methods include:

- A dedicated movement or stretching routine for the lower body (Yoga or otherwise)

- Learning proper hip hinging mechanics and performing hip hinging exercises

- Self soft tissue mobilization, such as foam rolling or vibration rolling (I personally prefer vibration rolling based on what academic literature is finding)

- Heating the hamstrings with a heating pack (usually then followed up with one of the above strategies)

One point worth mentioning here is that while stretching can absolutely be beneficial (when done properly), ensuring adequate strength of your hamstring muscles is essential. A mounting pile of academic evidence either shows or suggests that muscle tension is often abnormally elevated in muscles that lack adequate strength. So, your best bet is likely to involve some combination of stretching/mobility work and dedicated strengthening of your hamstrings as well.

If you’d like to learn a bit more about the scientific aspects of this, you can check out this journal article: The Case for Retiring Flexibility as a Major Component of Physical Fitness.

Final thoughts

One-sided hamstring tightness isn’t unheard of – many individuals, including myself, often experience this issue. Thankfully, it is often a relatively straightforward process for getting the issue sorted out. The key, however, is to know why you’re likely experiencing this issue and which tissues in your leg are causing your sensation of tightness or discomfort.

Once you have a good understanding of why you’re likely experiencing this issue, take some time to incorporate appropriate interventions based on the affected tissue(s) or structure(s) in your body. Be consistent with working on getting things under control and you’ll likely experience a significant improvement as a result.

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!